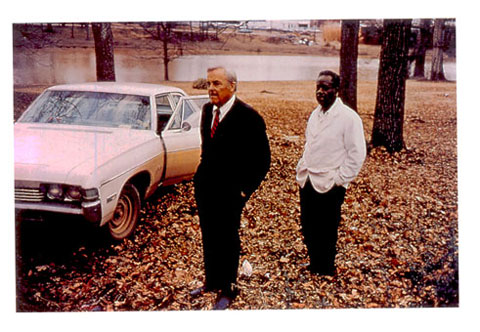

Photo by William Eggleston

Continuing my observations (from a few posts below) on the Eggleston show at the Whitney.

The exhibition at the Whitney is spacious, a whole floor of the museum. In my two recent visits the large holiday season crowds seemed involved in the work, not simply drifting through. A lot of people in the museum were obviously there to see the Calder exhibition upstairs. I was not, however, happy with the dimness of the gallery lighting, which reduced the vibrancy of the prints and gave everything a yellowish cast.

One of the reasons to go to the exhibit, as opposed to acquiring Eggleston’s books, is to see the dye transfer prints made at the beginning of his career–but the lighting muddied the experience for me. I don’t know if it was intentional–a concern about damaging the prints?

When I was at Cooper Union studying photography with Joel Meyerowitz I became aware of dye transfer prints. As I understood it at that time, dyes transfers were being used in advertising because of the saturated color and because it was possible to locally adjust color in ways not easily accomplished in so-called c-prints. Meyerowitz came from that world, doing commercial advertising, while shooting his early 35mm street photographs.

Shooting color slides, I was confronted with a dilemma. I could not afford dye transfers, could not make them myself, and therefore had to begin to learn how to make c-prints from internegatives. The quality of the lab-made internegs were mixed at best. And my first prints were not particularly good. Later, I gave up on slides and began shooting negatives, which translated better to prints. Getting there took some time.

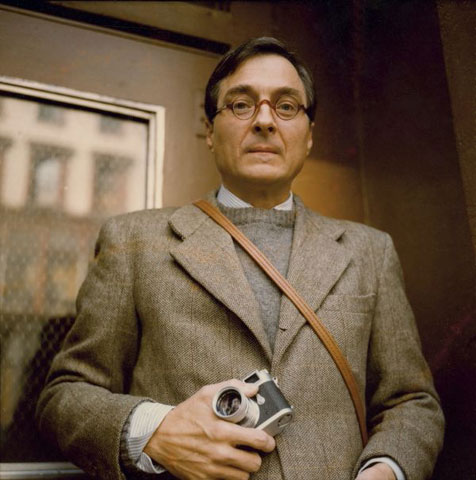

William Eggleston, photo by Maude Schuyler Clay

In realizing how costly dye transfer prints were, I also came face to face with a sobering reality: Eggleston was rich and could afford to shoot with abandon and print whatever he wanted using an expensive medium. This fact does not diminish Eggleston’s accomplishment, but it led me to a somewhat different reading of his work.

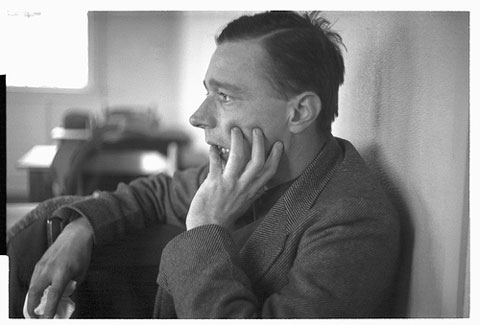

Walker Evans, photo by Edwin Locke

When one looks at Eggleston’s pictures or those of Walker Evans, another photographer of patrician upbringing, some consideration must be given to the sense of privilege inherent in the eye of the photographer. Evans, of course, in some of his best known work, trained his view camera on the downtrodden of the south–objective, attentive to every visual detail–in the process ennobling his subjects, whether human or architectural. But there was a clear separation between himself and those he photographed.

Eggleston, unlike Evans, is not much interested in humanitarian concerns as a photographer, but his seemingly casual, aloof reading of the world around him, allows the viewer to see social complexity coldly–sometimes in the harsh glare of a strobe–without the need for unnecessary compassion. (Compassion without clarity invites mawkishness.) In different ways, both Evans and Eggleston exhibit a freedom in their work unbeholden to sponsors or clients, but proffered, perhaps, with a measure of noblesse oblige.

More to come…