Photo by William Eggleston

Continuing my observations (from a few posts below) on the Eggleston show at the Whitney. The exhibition closes today, and I’ll wrap things up with a few observations made while walking through the galleries.

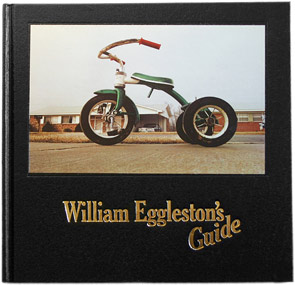

I began shooting color in the mid to late ’70s, and Eggleston was one of the few color photographers I knew about at the time. I had missed the famous Szarkowski exhibition at the Modern in 1976, but had seen the work published elsewhere a short time later. And I bought a copy of William Eggleston’s Guide–one of the groundbreaking books in the history of photography.

Initially, my interest in Eggleston lay more in his method and formal approach to subject. Eggleston probes with his camera, prodding here and there like a dentist. Does this hurt? What do you feel here? How about over here? He glances this way and that, up and down, sometimes level to the ground, sometimes tilted. His gaze seems all-inclusive, not hierarchical. Every scene, every object, every moment is in play.

In some ways his most famous images are outliers, least typical of his way of seeing. With such an even handed approach–democratic, as Eggleston says–the most iconic of his images shouldn’t be any more important than any others. And in fact, they are not. The tricycle on the cover of the Guide, for instance, is sometimes represented as a child’s view of the world, but it’s actually taken from a lower worm’s eye view. It’s another visual experiment like pointing the camera into an oven or refrigerator. The tricycle, rather than intentionally elevated to a monumental status, merely looms large–and strange–from Eggleston’s restlessly exploratory camera. Eggleston is not attempting grand visual statements, except perhaps incrementally. He’s slicing and dicing, taking MRI’s of America, each image a thin sliver of the body politic.

Photo by William Eggleston

Photo by William Eggleston from Election Eve

Looking at the Democratic Camera at the Whitney, I find now that Eggleston’s experimentation is, perhaps, subsumed into a larger cultural and regional perspective. The south plays a larger role in Eggleston’s work than he, probably, would like to admit. His best work, as I see it, is more about atmosphere than formal composition. One of my favorite series is Election Eve, a seemingly random collection of photographs redolent of the peanut fields of Plains, George, the hometown of then president Jimmy Carter.

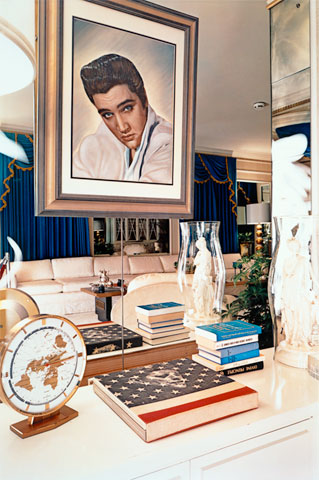

Photo by William Eggleston from Graceland

Eggleston also handles the garish décor of Graceland well, relishing the kitschy glam and dross of Elvis’s home without critical disdain. On a text panel accompanying the Graceland photos, Eggleston is quoted as not being interested in Elvis. I doubt that he would admit to being truly interested in anything he photographs. But in the company of Elvis–southern royalty, as it were–he is right in his element.

It can be said that Eggleston’s style is southern gothic, a latent sense of malevolence–a boy prostrate on a garage floor, a girl in a flowered dress sprawled on the grass, men with guns, women with big hair, slackers, drifters, marginal characters–Eggleston seems to relate–floating through a landscape littered with signage, suburban clutter, odd juxtapositions. It’s been mentioned elsewhere the influence on David Lynch and other filmmakers, but he’s, perhaps, better described in the company of Tennessee Williams or Faulkner minus the narrative.

No, Eggleston doesn’t escape his southern upbringing, despite denials, or his patrician mien. Ultimately, he is an itinerent carny, performing brilliant visual feats–recognized far and wide–but still coming off a little creepy, smelling faintly of liquor, living without the obligations that tie most of us down.

Here’s what it comes down to me. The slight-of-hand in Eggleston’s work is manifest as an incisive gaze rendered indifferently. This dichotomy—precision vs. spontaneity—is the essence of the Eggleston achievement. As a photographer, what I take away most from Eggleston is his cold-blooded equanimity in pursuing his glorified hobby. Everything is fair game for one’s attention, however transient that attention may be. Eggleston is quoted in the exhibition: “I had this notion of what I called a democratic way of looking around.”

What I understood immediately upon seeing Eggleston’s work back in the ‘70s was the idea of always moving. Snap, move, snap, move. It either happens or it doesn’t. There are no missed photographs, no regrets.