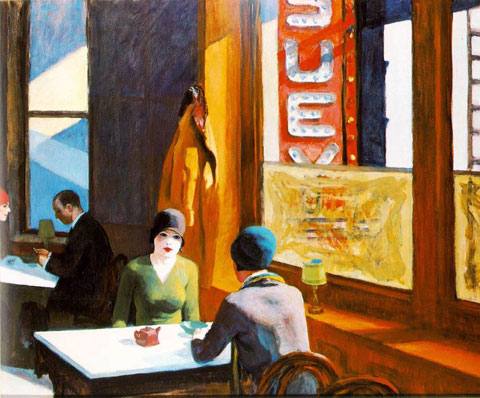

Edward Hopper, Chop Suey, 1929

Hopperesque. It’s a term that’s been thrown around for years to refer to art or literature that evokes the singular environments of Edward Hopper’s paintings. It’s a cliché–not necessarily used disparagingly–in fact, it’s most frequently used as praise. But as a cliché it isn’t the most helpful or insightful way of describing someone’s work. Maybe it’s a starting point to go deeper into things, which is fine, but by itself, it’s limiting.

Times Square, around 1990 — © Brian Rose (4×5 film)

In the Sunday New York Times, Jori Finkel writes about a show at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco that explores the relationship between Hopper and 20th century photography. It features seven paintings and a larger number of photographs made, primarily, by photographers represented by the gallery. Insert red flag here. Is this a serious show meant to challenge us to think about Hopper and photography, or is it a vehicle to promote the work of some of the most well-known photographers in the world? I haven’t seen the exhibit, nor do I know Jeffrey Fraenkel the gallery owner, so I don’t want to be overly judgmental. And I understand that it is the business of galleries to sell photographs. Still… Is this a show that justifies a large chunk of print in the paper of record?

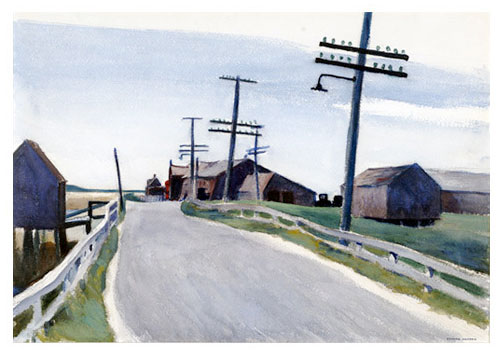

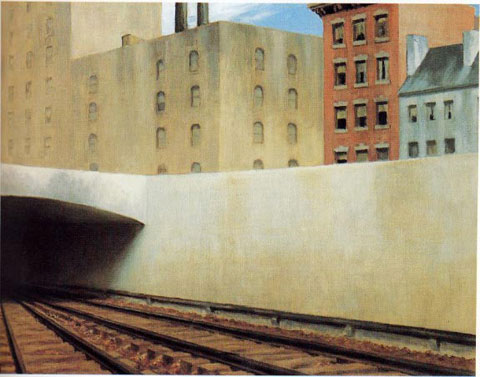

Hopper’s work while often referred to as depicting loneliness and alienation, especially in an urban setting, is also widely appreciated as a painter of the American landscape. Not the heroic landscapes of the 19th century painters enthralled with nature and manifest destiny, but the more prosaic ones found on winding country roads or city street corners. He was modern in that sense. He painted common places and fleeting moments in the play of light both natural and artificial. He did it with a lush palette of fat paint, but the canvasses themselves were of modest size, simple compositions, unadorned, plain and direct. His often solitary figures were caught unaware, so it seems, and we look on almost voyeuristically. We apprehend the sliver of a story, a frame of implied narrative, and sense the inner life of characters, though we can’t know exactly what occupies their thoughts.

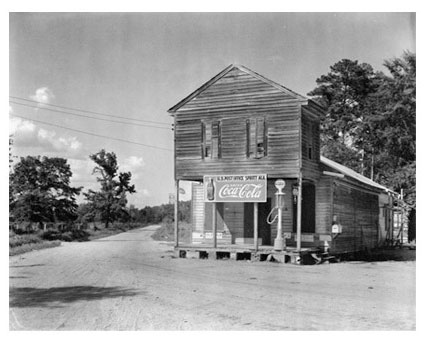

It’s easy to see the relevance to photography. But my feeling is that the obvious kinship between Hopper and, say, Evans or Shore is, perhaps, superficial. I know from my own experience as a photographer, and one who has spent an enormous amount of time in galleries and museums, that many types of art–from representational to abstract to conceptual–have had an influence on how I see the world and how I make pictures. I suspect it must be true for most other photographers.

Edward Hopper, Wellfleet Road 1931

Walker Evans, Post Office, Sprott, Alabama, 1936

From the Times article:

“Hopper is huge,” Mr. Fraenkel said. “I think he’s had a pervasive impact on the way we see the world, so pervasive as to be almost invisible. Jackson Pollock is one of our greatest artists, but we don’t see Pollocks everywhere we look.”

The Bronx, 1985 — © Brian Rose (4×5 film)

Personally, I do. I don’t know about other people, but I cannot look at the world without referring to the vision of all those painters who have taken apart and reassembled the world for us over the past century. From Cezanne who saw structure underlying everything to Mondriaan or Rothko whose reductive canvasses–in radically different ways–tested the connection of painting to the real world out there and the psychological or spiritual world inside. In recent years those who have questioned the utility of photography as description of the real have forced us to alter our understanding and connection to that which we perceive around us. All of this stuff gets assimilated into one’s thinking–though once I hit the street with my camera I am more lizard brain than art historian.

Stephen Shore, Holden Street, North Adams, Massachusetts, 1974

Edward Hopper, Approaching a City, 1946

Gerrit Berckheyde, The Golden Bend in the Herengracht in Amsterdam, c. 1672

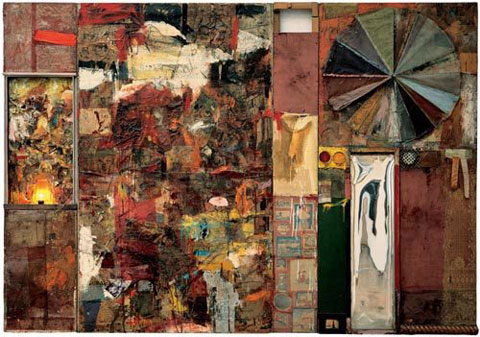

I have no doubt that the photographers shown in the Fraenkel Gallery have looked at Hopper, and possibly thought about him quite deeply. But the fact that Hopper paintings look a lot like certain kinds of contemporary photographs does not necessarily make them more relevant to photographers than paintings by other kinds of artists. If you go down a few posts, I wrote about looking at the Dutch landscapes of the Golden Age, and how they reminded me of the way the view camera takes in the world–the breadth of the landscape and the smallest details from foreground to background. But I could just as easily talk about the way Robert Rauschenberg integrated found objects, printed images, and seemingly random detritus into his paintings–and as a result I noticed that the real world was often like that, too. The list goes on.

Robert Rauschenberg, Charlene, 1954

Here’s Fraenkel again at the end of the Times piece:

“It may just be me — it may just be my imagination — but I believe in this enough to put it out there,” Mr. Fraenkel said. “There may be dissenting viewpoints, and you can’t just say a light post near a house means influence. It’s much more complex than that.”

More complex, indeed.