Cartier-Bresson banner, Museum of Modern Art — © Brian Rose

As is so often the case these days, photography is not allowed in the current Cartier-Bresson exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. So, my pictures are peripheral to the galleries themselves–a banner outside, the gift shop, the entry and title wall to the exhibition. It would be helpful in writing about the organization and content of the show to be able to speak visually, that is, by taking pictures. Once again, visual speech denied. Nevertheless, the museum has provided a significant portion of the exhibit online here.

Maps and exhibit title in MoMA — © Brian Rose

Prints on demand, MoMA, classic Cartier-Bresson image — © Brian Rose

The first thing one encounters entering “Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Modern Century” are several large maps that trace Cartier-Bresson’s wanderings across the globe over the decades he worked as a photojournalist. It’s not the way his work is usually presented, typically a distillation of his most iconic images, especially the “decisive moment” photographs of the 1930s when he developed his groundbreaking way of seeing. I was happy to see curator Peter Galassi take a different approach, thematic and geographical, that while hitting all the high spots of his career, also revealed how many of these photographs came from specific assignments published in the lavishly illustrated magazines of the day. It is important to understand that the “art photography” of Cartier-Bresson was made in an entirely different context from present day gallery photography. The overtly self conscious nature of much contemporary photography is nowhere to be found in Cartier-Bresson’s work.

Seeing the range of Cartier-Bresson’s images at MoMA spanning decades and continents I was stunned, yet again, by the epic scale of his achievement. Not only did he essentially invent 35mm street photography, and create a purely photographic way of responding to time and composition, his work touched or intersected with many of the great events of the 20th century. And his portraits of leading artists of the century, alone, would have established him as an important photographer.

Venice, 1953, photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Having looked at a lot of Cartier-Bresson photographs over the years, I was most interested in the many images in the exhibition that I’d never seen, especially the views of crowds, the pictures made in America, the depictions of working men and women. One photograph, new to me, taken in Venice in 1953 shows the pointed prow of a gondola juxtaposed against an arched bridge reflected in the water to form a nearly completed oval, a tower jutting vertically behind, and a girl in motion crossing the bridge. It’s a classic Cartier-Bresson image, visually modern, but a fleeting glimpse of a timeless Europe.

Photography by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Garry Winogrand?

Photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson

Lee Friedlander?

In the New York Times Holland Cotter ends his mostly positive review of “The Modern Century,” curiously I think, by comparing at some length Cartier-Bresson’s American images to those of Robert Frank. Frank and other small camera photographers like Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand were directly influenced by Cartier-Bresson, but I think of them in relation to newer cultural movements–Frank to the Beats and the stream of consciousness style of Kerouac, Friedlander and Winogrand to pop art and the jarring political and social clashes of the 60s and 70s. Their careers overlap, true, but Cartier-Bresson was a product of an earlier European sensibility, attuned to cultural difference and identity–that combined with the peripatetic restlessness of a reporter touching down briefly, then on again to the next assignment. When Frank set off across the United States, he was not reporting from the road; the road became its own reality, leading to places unknown.

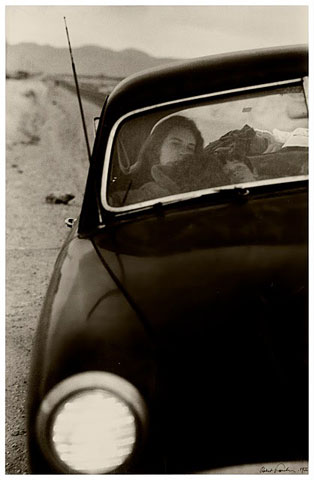

Photograph by Robert Frank, 1955

Frank’s “The Americans” is arguably the most influential photo book of the 20th century. Conceived as a project, based on a single body of work, it remains a profoundly insightful, disturbing, portrait of the American social landscape. But nothing Frank did, nor anything any of us do as photographers, is conceivable without Cartier-Bresson. He was the great innovator of “The Modern Century,” as the show at MoMA makes imminently clear.

.

***

.

After seeing the exhibit I walked with my friends Art Presson and Eve Kessler through Times Square over to a restaurant on West 44th Street. It was a warm, pleasant evening, the streets teaming with people. My wife and son joined us at the restaurant, and after eating we headed downtown just a few minutes before Times Square was evacuated due to the discovery of a car bomb–fortunately unexploded. We were oblivious to the drama until I checked the news on the Internet later in the evening.