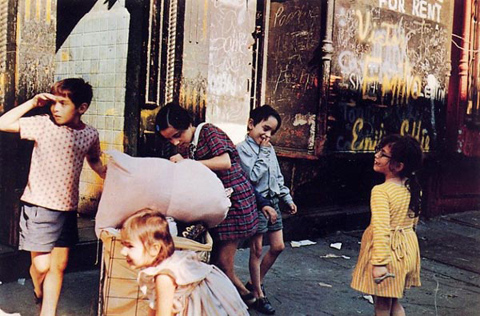

Houston Street and MacDougal — © Brian Rose

I saw the MoMA ad for the Cartier-Bresson show and began taking some snaps through the chainlink fence. Within seconds I was accosted by a man who requested/demanded that I stop photographing the children. I told him I was photographing the whole scene, not the kids in particular, and that I would not take any more pictures, because he had asked. As I began to walk away, a girl on the other side of the fence asked if I was “videoing” them, and I answered, “no, just still photos.” The man, presumably a teacher at a nearby private school, then admonished the girl for talking to me, saying “you know what we’ve said about people like that.”

I understand the concerns about protecting children from predators–I am, after all, the father of an 11 year old boy–but this is simply another example of the demonization of photographers. Had I wanted to surreptitiously photograph the kids, I could easily have done so without being noticed. Moreover, I was standing on a public street, and the students were using a public park, not even a private school playground, for recreation. A pattern of undue interest might well be considered worthy of some level of intervention. But simply taking photographs in a public place where kids are playing does not constitute suspicious behavior, and it is certainly not illegal.

More photos of children in public places:

That’s the problem with people like you, I mean us- I mean them…

Just wondering- how many times did you have people from East Germany demand you stop taking pictures?

Well, East Berlin, the only part of East Germany that I went with my camera was pretty nerve wracking. But I have to say, in the first four or five days that I carried around my view camera, no one demanded that I stop taking pictures. Going through the border checkpoint, however, I was, on several occasions, taken into a small interrogation room and quizzed on my activities. I always said I was interested in the German architect Schinkel, whose most noteworthy buildings were in the east. Things were going okay until I accidentally ended up photographing Stasi headquarters–the secret police. I figured it out later. Uniformed guards with guns started yelling and began heading my way. Fortunately, I was standing directly next to a subway entrance, ran down the stairs, and stepped onto a train arriving right at that moment. I doubt that my interest in Schinkel would have worked this time had they caught up to me.

What I see happening here is an increasing desire to control the public commons, and a troubling willingness on the part of many to allow various kinds of authority, whether it be police or citizen busybodies, to restrict public freedom in arbitrary–and often unconstitutional–ways. Photographers, because of the nature of what we do, and the fact that we so frequently occupy and do our art/business in the public domain, are like canaries in a coal mine with regard to personal freedom. And we’re gradually losing it.