The phone burbled, it was a text from my painter friend Tim Raymond. He was on the road heading down from Buffalo, the city where he somehow had found himself marooned some years ago. I’ve known Tim since the mid-70s when we lived in Baltimore–I was an art student at the Maryland Institute for a while, and I’d met his wife Cathy who was a fellow student. Tim and I have things in common. We are both graduates of Cooper Union, though attending at different times, and we were both bicycle messengers in Washington, D.C., though also at different times. And we’re both artists, still hanging in there after years of less than resounding success in the marketplace.

Luncheon of the Boating Party, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the Phillips Collection

Back in my D.C. messenger days, when work was slow, I’d often retreat to the Phillips Collection with its glorious collection and intimate scale. I developed special relationships with a number of the paintings in the museum, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s tour de force Luncheon of the Boating Party. It’s easy to write off Renoir, who produced an enormous amount of gauzy fleshy dross alongside a generous number of masterpieces. The Boating Party is rigorously ordered, full of oblique compositional lines, echoed by the sidelong glances of the various figures, punctuated by the dappled light, sprinkling of red lips, and the almost palpable tinkling of wine glasses and murmur of overlapping conversations. I could go on.

Tim’s text also included, cryptically, that he was coming to New York to see a Renoir, which I couldn’t make any sense of. The next I heard from Tim he was struggling to park on 34th Street near 5th Avenue, and had already managed to get a parking ticket for leaving his car in a loading zone. Once I had helped extricate Tim and his car out of the traffic maw of Manhattan, he filled me in about the Renoir.

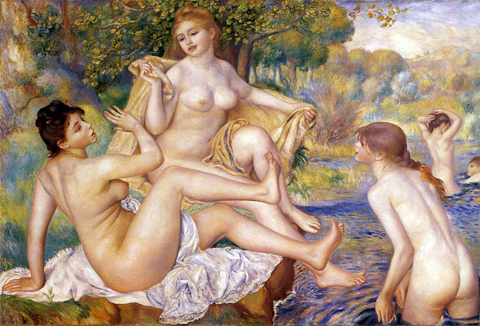

The Large Bathers, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The Philadelphia Museum

Ten year ago, Greg Kitchen, an old acquaintance of Tim’s ex-wife had bought a pastel at an antique sale of two nude bathers signed “Renoir” at the bottom. He paid less than $200 for it. Assuming its legitimacy, it is a highly detailed study for Renoir’s Large Bathers painting, which hangs in the Philadelphia Museum, and could be worth a fortune. Kitchen, so it seems, has been getting the run around from the auction houses and dealers unwilling to seriously consider the authenticity of the drawing. In Tim, he hoped to find an ally and someone who could help him better present his case.

Tim showed me a photo of the pastel on his iPhone, and I was immediately doubtful. The drawing appeared too polished to be a study–and too much about line and volume–while Renoir is known more for his light and color. But Tim convinced me I should come along with him to meet Kitchen and hopefully see the original piece. We arrived at his loft on W28th Street in a raucous part of Manhattan full of cheap fashion wholesalers who are periodically raided for selling counterfeit brand name merchandise. It seemed the appropriate place for a Renoir forgery.

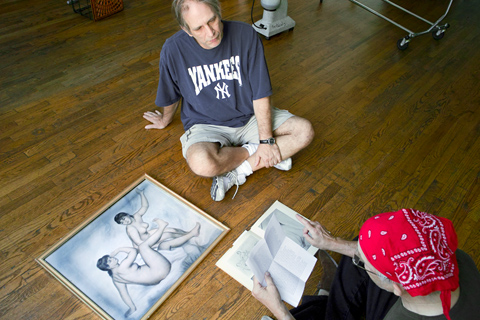

Greg Kitchen, Tim Raymond, and the Renoir — © Brian Rose

Kitchen laid out his case for the authenticity of the drawing in a rambling narrative, displaying various documents, letters, and research material. It was clear to me as an outsider with no vested interest that he needed a much more organized and believable presentation of the facts. Nevertheless, I came to understand that the tests Kitchen has had done on the paper and pigments all support the authenticity of the drawing, though none represents definitive proof. Forgeries can be incredibly sophisticated. A full size photograph of the bathers was laid out on the floor of the loft, and it appeared to me, still, unconvincing. I sat on the windowsill of the loft gazing up a the Empire State Building looming above the decorative railing of the fire escape. But as I thought more about the what Renoir was trying to do with his Large Bathers, the drawing qualities began to make more sense. Here’s some text from the Philadelphia Museum website:

The sculptural rendering of the figures against a shimmering landscape and the careful application of dry paint reflect the tradition of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French painting. Renoir—in an attempt to reconcile this tradition with modern painting—labored over this work for three years, making numerous preparatory drawings for individual figures and at least two full-scale, multifigure drawings. Faced with criticism of his new style after completing The Large Bathers, an exhausted Renoir never again devoted such painstaking effort to a single work.

The Empire State Building from W28th Street — © Brian Rose

This drawing, which is clearly not a copy of any of the other studies, could represent an attempt by Renoir to fully flesh out, as it were, the volumetric qualities of the female figures before proceeding to the actual painting. There was only one thing to do–see the original–presently locked away in a Chelsea storage facility. So, Tim and I trailed Greg Kitchen ten blocks over to the West Side. I snapped another Empire State Building image along the way, this time a vinyl ad stretched over some scaffolding.

Image of the Empire State Building — © Brian Rose

The drawing was stowed in a standard mini-storage closet, packed in a nondescript cardboard box held together with packing tape. Kitchen opened the box and removed the foam and bubble wrap swaddling his precious find. And there it was. Astonishing. A depth of volume and color, a presence, completely unavailable in the photo we had looked at earlier. There were details in the surface, scratch marks, erasures, the ghostly evidence of a third figure on the right corresponding with the composition of the finished Large Bathers. The skin of the most forward of the figures was opalescent, the faintest hint of blue veining showing through. If this wasn’t a genuine Renoir, then it was a masterful forgery.

A Girl with a Watering Can, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, The National Gallery of Art

Seeing the pastel in person, I was reminded again that Renoir was often the maker of insipid images. Divorced of the visceral quality of the paint, they have become icons of bourgeois sophistication–like the crappy reproduction of a Girl with Watering Can that hung over the piano that no one ever played, in the living that no one ever used, in the faux colonial ranch house I grew up in. We are consumers of images with little connection to the materiality, the texture of the real, whether it’s a painting or the fabric of life itself. But, I digress.

Tim and I left Greg Kitchen on the corner, strolled the High Line down to the Meat Packing District, and retreated to a beer garden under the rail viaduct. It was blissfully cool in the shade, mild weather, following a stupifyingly hot July. It was clear, despite our reaction to the actual drawing, that this was going to be a difficult case, a complex mystery to unravel. There had been a robbery in Renoir’s studio in the late 19th century. Had the drawing been stolen? The last known owners were in Switzerland in the 1940s, and inquiries there had gone nowhere. There were intimations of nefarious doings–had the drawing been appropriated from Jewish owners doomed to Hitler’s gas chambers?

It’s now Tim’s job to clean up the narrative and collate the existing documentation. He and I are laughable amateurs in the world of international art intrigue. Ultimately, this will come down to the art experts, the lawyers, all who will extract their pounds of flesh. Or as I joked with Tim, Kitchen could always take it to the Antiques Road Show on PBS. Imagine, a drawing signed by Renoir bought at an antique fair for under $200, turns out to be a genuine figure study for one his most important paintings, worth–say–$2,000,000?

Hi Brian! Enjoyed your recounting of your day with Tim and the Renoir. Found your blog via Cathy’s Facebook post.

thank you for mentioning the renoir. that was nice.