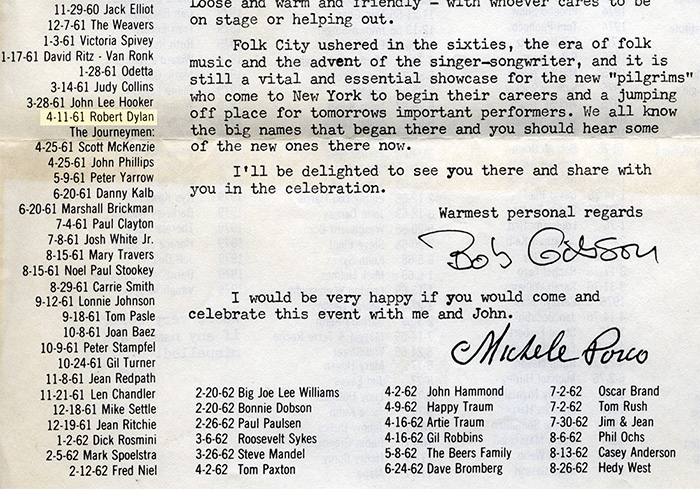

Close up of Folk City 20th anniversary flyer (1979)

4-11-61 Robert Dylan

In many respects, Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize in literature is an affirmation of what those in my songwriter circle have been doing for decades – crafting songs in which music and lyrics interlock in poetic balance. Is it literature, or something else? Certainly, Dylan’s lyrics were not meant to stand alone on the page, though many of his lines and phrases have become as familiar as Shakespeare or the Bible.

My old friend, the songwriter Jack Hardy, now deceased, would have probably sneered at Dylan’s Nobel accolade – after all, in Jack’s demimonde of folk music, Dylan was a sellout. He was/is a pop star of tremendous fame and fortune. That makes him a problematic figure to some, but I see his hyper success, to a great extent, as a product of the 60s, when songwriters and rock bands burst onto the scene promoted by an expanding record industry and the rich diversity of free form radio. He tapped into the cultural revolution of the moment – as did the Beatles – and his songs were disruptive and catalytic, both in social and aesthetic terms.

It’s harder now. There are a million more opportunities to get one’s work out there, which is a good thing, but the method of distribution is atomized, and audiences break down into smaller and smaller niches. The shared experience of a stunning new song crackling across the airwaves such as “Like a Rolling Stone” or “Tangled up in Blue” is largely a thing of the past. We now rely on youtube videos, streaming music, or other electronic forms of connective tissue.

For many songwriters that also means doing it the old fashioned way, playing to people directly, making tours of small clubs and even living rooms. And in fact, the kind of song that Bob Dylan mastered was the outgrowth of an oral tradition deeply rooted in western culture, cross-pollinated by influences from the African diaspora in North America. Jack Hardy would have called it the bardic tradition (minus the lyres and leprechauns, please), and he was right. The kind of song that Dylan cultivated and ultimately transcended was based on an ancient means of lyrical communication that pre-dates what we think of now as literature.

So, I’d like to think that the Nobel committee has recognized one of the greatest and most complex artists of our time not so much for extending the boundaries of literature, but for reconnecting us to the roots of literature itself.

Bob Dylan had a history of being playfully evasive toward the reporters during the advent of his rise to fame. At least that had been the impression I’d gotten in combing over the wonderfully insightful articles on musicians compiled from published editions of the Village Voice. I suppose it is incumbent on all of us, his mostly adoring public, to wonder what motivates and inspires this celebrated composer to be in abeyance of his recent and rightfully earned title in nobility. Perhaps it is owing to innate feelings of shyness, or perhaps some revulsion at the thought of playing into hand of others who would capitalize on his success, or through recognition would lead to the aggrandizement of any institution no matter how lofty. It is right for us not to know so long as Mr. Dylan would have it that way. That which is admirable is the the troubadour’s willingness to soldier on in bringing to us his particular insight into who we are and his take on understanding the world we have come to know.