2020 has been an extraordinary year, to say the least, and it is not over yet. Despite all the derangement and turpitude of Trump, and despite the Covid-19 pandemic with its toll of death and social isolation, it has been a productive time for me as an artist and photographer.

This period of time actually begins for me in November of 2019 when I traveled to Berlin for the 30th anniversary of the opening of the Berlin Wall. The documentation of the former East/West border has been a lifelong project for me, and I have continued to follow developments in Berlin, particularly along the path of the Wall and the swath of no man’s land that once divided the city and surrounded its western half.

Although most of the Berlin Wall was torn down within months of its opening on 9 November 1989, there were several stretches that remained, most notably adjacent to the Topography of Terror site with its below-grade view of the foundation walls of the SS/Gestapo headquarters. Looming just beyond the Wall is the former Nazi air ministry headquarters. It’s a visual compression of history that I have photographed several times over the years – this time, the exhibition panels mounted against the brick wall were temporarily down, which I think makes the image stronger.

There are individual slabs of Wall still standing scattered about the city. Some moved a slight distance from their original positions like the two ivy-covered pieces above.

Berlin has much gravitas as a city possessing the weight of history, but it has also surrendered to a baffling amount of kitsch. Artifacts of its communist DDR days, mostly fake, are plied by vendors, and you can ride in an original East German Trabant at Trabiworld just across the street from the Topography of Terror. I guess it’s possible for the silly and the serious to coexist peacefully, but the juxtaposition is jarring, nevertheless.

Although I have already had some of this work published in “The Lost Border,” back in 2004, which includes pictures of the landscape of the Iron Curtain, there is another book here that focuses on Berlin alone. Very little of this work has been seen, and I hope to eventually do something with it.

During the winter months, I began adding to a body of work I’ve been gradually accumulating, of photographs of the High Line and the urban landscape surrounding it. I also have about 20 or 30 photographs of the area taken in 1985. The new pictures are not so much about the former rail viaduct itself, which was brilliantly reinterpreted by architects Diller Scofideo & Renfro, but about the way in which the elevated structure cuts through the fabric of the city, redefining space and architectural relationships. The High Line has, of course, also become a tourist attraction, and its presence has spurred development and gentrification, ironically, given the fact that real estate interests were originally against it. The story of the High Line is complex, but as a dynamic intervention in the urban landscape, it is fascinating and a visually rich subject.

I was just getting some momentum going on my HIgh Line project when the coronavirus pandemic hit. I remember sitting in a cafe with a friend showing him 8×10 work prints of my pictures realizing that this might be the last time we’d be able to do something like this for a while. He was planning on leaving town, and I was unsure what to expect going forward.

One of the last pictures I took during the winter before the Covid lockdown began was an image of a homeless man in the subway station at 8th Avenue and 14th Street. As a general rule, I do not seek out people in distress to photograph. Nor do I photograph people who are completely unaware of my presence. It’s not a hard and fast rule, exactly, but a self-enforced guideline I follow.

In this case, I walked by, noting the man out the corner of my eye, but within a split second came to a quick stop and circled back. I’m not sure how much of the details of this image I was able to process in the moment, but I knew there was something here besides a homeless man lying on the floor. The prostrate man was echoed by a man lying on the ground in the advertisement above. There was a hashtag, or number sign, in red floating over the image, which echoed the red worn by the homeless man. The grid of the hashtag echoed the grid of the sidewalk, the tiles of the subway station, and the tiles of the floor. The prosperous appearance of the men in the ad accentuated the difference seen in the man attempting to sleep on the floor of the subway. While two horses pulling a carriage approached from the right of the advertisement. It’s an enigmatic image – a little disturbing, perhaps.

In March the pandemic swept over the city. Most businesses and restaurants were forced to close, takeout and groceries excepted, schools closed, and what would normally be a time of release with people pouring into the parks as the weather warmed up, was, instead, a period of frozen suspended animation. The photograph above was taken during the first days of the lockdown. Trees flowering, empty streets and parks. Like nothing I’d ever seen in all my years in the city.

At the height of the lockdown it was still possible to take walks, and I began going out with my camera regularly. What started out as a casual bit of picture taking morphed into a full-blown project. I ended up making 16 walks through our neighborhood of Williamsburg, Brooklyn from about March 20th to April 20th. I realized while doing the project, that no one had really photographed Williamsburg, as famous a place as it is, in a comprehensive way.

What I found on the streets of Williamsburg was a city more diverse and idiosyncratic than I expected. The gentrification of the neighborhood was obvious, especially closest to Manhattan. But the photographs also show a place bedraggled and graffiti-covered, multi-ethnic, and often poor. There are distinct quarters: the orthodox Jewish enclave to the south where maskless crowds continued to congregate, and the adjacent Latino tenements and low-income projects. The streets around the massive Woodhull Medical Center on Broadway were littered with people who obviously had nowhere to go, also maskless. I often walked in the street to avoid this flotsam of downtrodden human beings. Ambulances passed frequently, sirens piercing the pandemic quiet.

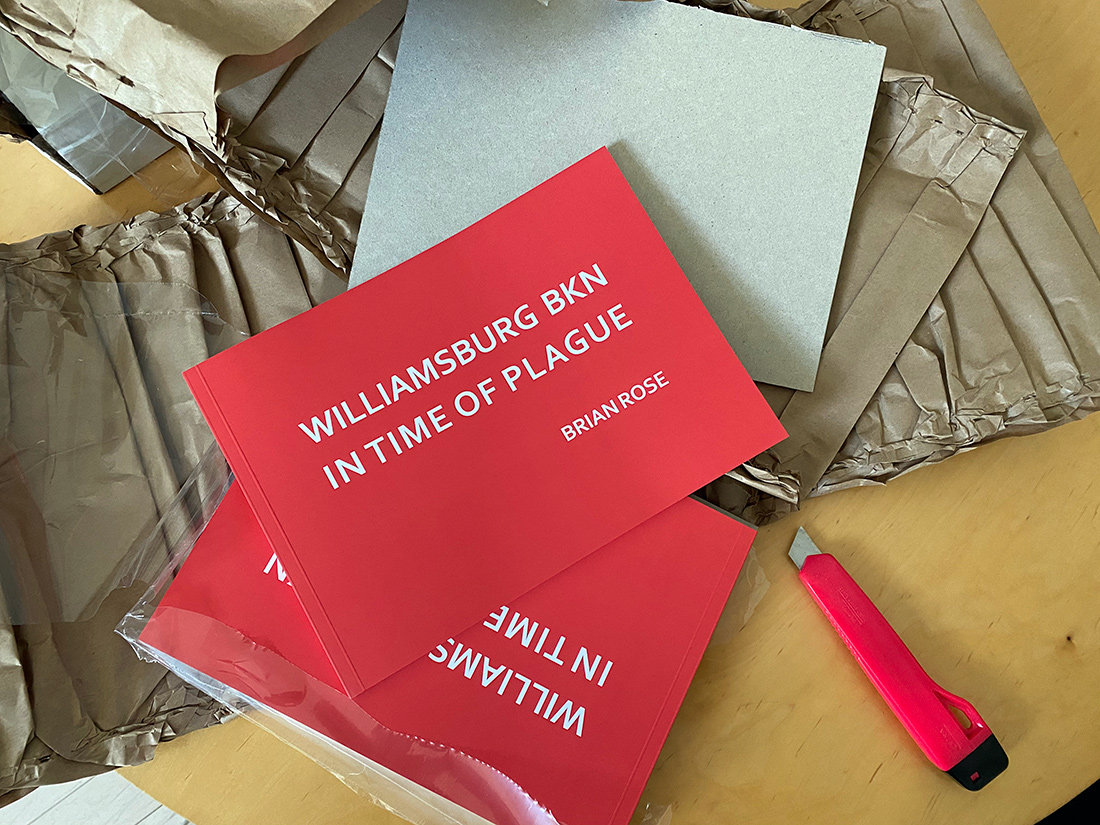

At some point, I realized that this body of work was developing into something more deeply resonant than a simple documentation of a well-known place. I made a couple of attempts to find a publisher but quickly realized that I would have to do this on my own. I put together a Kickstarter campaign and raised the money I needed to print the book and get it out. The book is called “Williamsburg: In Time of Plague.”

To be continued…