The New York Public Library (digital)

My visit to the New York Public Library to see Eminent Domain, a photography exhibition about New York City, started off well enough. Walking in to the building I noted that “flash photography” was not allowed, but was happy that I would be able to take pictures inside. I walked through the entrance to the exhibit and began reading the introductory text:

As the proposed regulations on photographing in New York City illustrate, photography is often subject to such private/public complications. Indeed, issues of privacy and image rights have troubled photography throughout its history; with the shift to digital media and the increasing regulation of public space (both literal and virtual), these issues are becoming even more complex. A photograph, after all, is a transaction between the private and the public that is negotiated through the taking of an image—a kind of eminent domain of the visual realm.

Stephen C. Pinson (curator)

Having read the text, I wandered about the dimly lit gallery waiting for my eyes to adjust to the dark. It’s a beautiful room, and the exhibit itself was nicely designed, but the darkness was problematic. The photographs deserve a brighter, cleaner, more neutral environment.

Eminent Domain • Ethan Levitas photos (digital)

As I leaned my camera against a column to do the image above, a guard ambushed me, barking loudly, “No photography allowed! I told you when you came in. Put away the camera.” My 9-year-old son was a bit shocked to see his father reprimanded with such harshness. I had unwittingly committed the crime of taking a picture of an exhibition relating to the increasing “regulation of public space (both literal and virtual).” Oops.

Still a little shaken by the reprimand, I looked around the exhibit. Nothing in the show itself had quite the impact of the guard’s presumption of authority over the act of photography. The concept of eminent domain and the myriad implications of the phrase should have resulted in an exhibit of challenging work that addressed the blurring of public and private realm, not to mention the way in which government employs eminent domain for purposes that seem to make public good and private profit interchangeable.

Thomas Holton

Jacob Riis famously photographed the living conditions of immigrants in their tenements on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. His pictures were intended to shock the pampered consciences of the respectable class of Manhattanites. Riis’s high moral dudgeon achieved results in the social sphere, but one perceives little empathy in his pictures. His flash powder explosions of light remain powerful and pitiless depictions of poverty. In comparison, Thomas Holton’s well-intentioned pictures of family life in Chinatown seem too respectful, too careful of the relationship built up between photographer and subjects. I found myself wanting something more intrusive, personally riskier. I like the photo above the best because, for once, the interaction between participants is openly acknowledged.

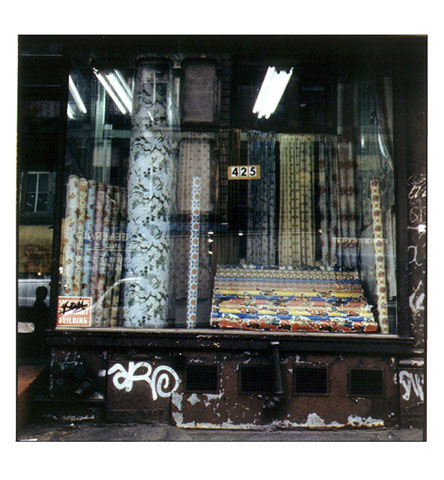

Zoe Leonard

Zoe Leonard’s square format images of Lower East Side garment businesses and the like were attractively nostalgic, but too casual, off-hand. It’s hard to believe the accompanying text refers to these images:

Although centered on the Lower East Side and Brooklyn, the completed project (an archive of about 500 images) captures the wide-ranging forces of globalization, with specific attention to the route and final destination of New York’s castoff clothing in the contemporary rag trade. As such, Analogue is not only a meditation on the costs of urban redevelopment, but an exploration of the replacement of local markets by a global economy. As its name suggests, Analogue is also an elegy of sorts to a long-standing tradition of documentary photography, from Atget to Walker Evans, which Leonard sees passing with the onset of digital photography.

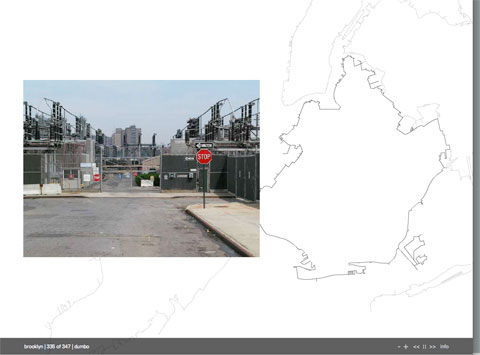

Betinna Johae

Bettina Johae’s ambitious project in which she traveled the periphery of the city’s five boroughs floats in limbo between a conceptual piece and a collection of individual images. Some of the photographs are mounted on the wall on movable pages that can be leafed through, and others are shown on small video monitors. The mounted photos are not well lit, and the considerably brighter back-lit images are pixellated even at small size. The website is the best way to see her work.

Ethan Levitas

Ethan Levitas’s subway cars are the strongest images in the show, each train car (or parts of two cars) photographed at the same distance capturing people framed in the windows. We see faces, backs of heads, gestures, flecks of color and pattern–people in public, but suspended in moments of private isolation.

Reiner Leist

Reiner Leist has photographed the scene outside his studio window almost every day for over 10 years using an 8×10 view camera. The images are murky and hold little detail despite the 8×10 format. Different household objects are seen in the foreground on different days. During the making of the series, the Twin Towers disappear. The book costs $85.

New York has undergone historic transformation in recent years, first rising from financial collapse and the rubble of the ’70s and ’80s, and then, at a quickening pace, rising from the ashes of September 11. There have been profound dislocations of neighborhoods, while the population has continued to increase, diversify, and stratify. New York careers forward in the midst of a new gilded age, an era of mega real estate projects designed by rock star architects held aloft on the ether of money while war grinds on far away in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Whatever the merits of the various photographers’ work, too little of this complex dynamism can be found in the exhibition at the Public Library.