Dorothea Lange exhibit at MoMA — © Brian Rose

I’ve always had a complicated relationship with Dorothea Lange’s work, and that of other “concerned photographers,” to use Cornell Capa’s oft-repeated phrase. As a young photographer, I rejected the style of photo-journalism promoted by Life magazine, and what I saw as the glib humanism of the famous “Family of Man” exhibition curated by Edward Steichen at the Museum of Modern Art. To me, there was an insurmountable gap between the steely-eyed gaze of Walker Evans and the empathetic eye of Lange. Evans pursued some of the same subjects – sharecroppers in the south, for instance – but maintained a certain distance. He described what he saw in stoic terms rather than attempting to express emotional engagement. That makes his images all the more powerful, in my view.

Dorothea Lange exhibit at MoMA — © Brian Rose

No, I haven’t changed my position. But this is a really beautifully conceived exhibition, curated by Sarah Meister, (@momameister) that makes a strong case for re-assessment. To an extent, Lange’s photography has been overshadowed by itself – by iconic images like “Migrant Mother” – one of the most famous pictures ever taken. This image and other touchstones of the genre obscure a more diverse approach in style and content than is generally known, and they tend to limit her multi-decade work to one time period.

Dorothea Lange exhibit at MoMA — © Brian Rose

One of my favorite pictures shows a young girl on a porch with a scrim of vines in front of her. It’s from Lange’s FSA work, still her strongest. The vegetation acts as both a framing device and a visual barrier. The composition is rectilinear, almost a Mondrian-esque grid. The specific context or rationale for the image is mysterious, but as a viewer, it is not always what you know, but what you don’t know that matters most. The caption reads: “Butter bean vines across the porch. Negro quarter in Memphis, Tennessee.”

Another image in the same grouping shows a somber-faced woman in a fancy automobile framed in an oval window. My first thought was of Rosa Coldfield, the embittered raconteur in Faulkner’s quintessential southern novel “Absalom Absalom.” According to a recent Times review of the show, John Szarkowski, the MoMA curator who first mounted an exhibit of Lange’s work in 1965, originally thought the image likely depicted a haughty, privileged woman looking out from her car. The title of the photograph, however, is “Funeral Cortege, End of an Era in a Small Valley Town, California.” The caption either expands or diminishes the meaning of the image, take your pick.

“Rose II” by Isa Genzken in the MoMA sculpture garden – © Brian Rose

“Dorothea Lange: Words and Pictures” is a wide-ranging exhibition not done justice by my few comments. I’m happy to see it for a number of reasons beyond the fact that Lange’s work deserves reconsideration. I do not think that photography benefits from the new interdisciplinary format of the Modern, and an exhibit like this one, demonstrates why. Like many photographs, these are best seen in isolation, untethered by comparisons to painters who may have dealt superficially with similar subject matter. The history of photography is integral to the history of art in general, but it also runs on a parallel track with its own sequence of developments and its own internal logic. I greatly miss the photography department with its comprehensive presentation of the medium’s history.

The other reason this exhibition is so timely is because of its social and political content. We are living in a moment when the kind of engagement seen in Lange’s work is desperately needed.

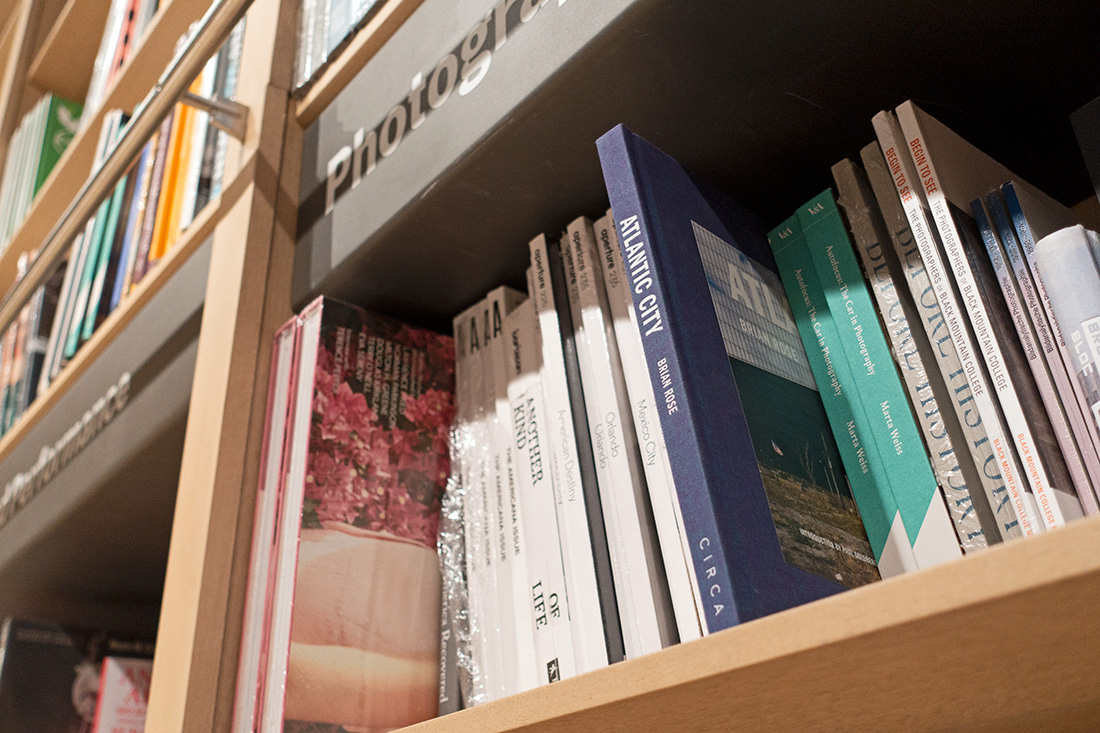

Atlantic City in the MoMA store – © Brian Rose

I made a quick stop in the museum store on the way out and was not terribly surprised to find myself missing among the “Rs” in the photo book section. “Atlantic City,” my portrait of a city in the aftermath of Donald Trump, has not found its way into all book stores – and truth be told, I’m not exactly a famous photographer – though I am in the collection of this place. But then, there it was! In the wrong place on the shelf.