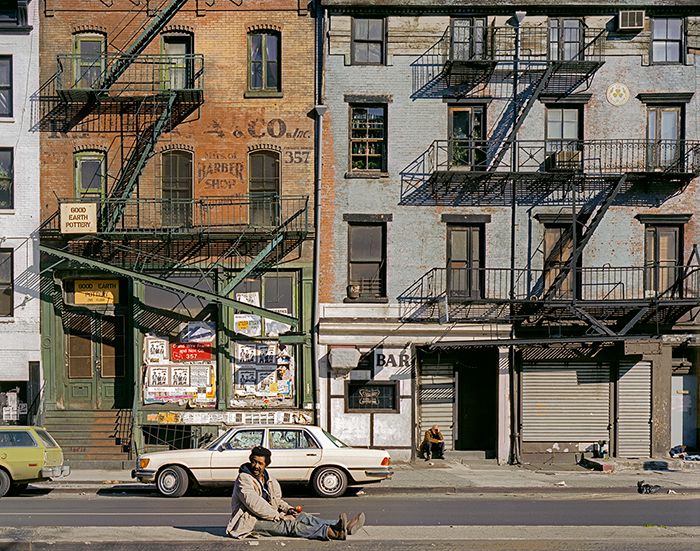

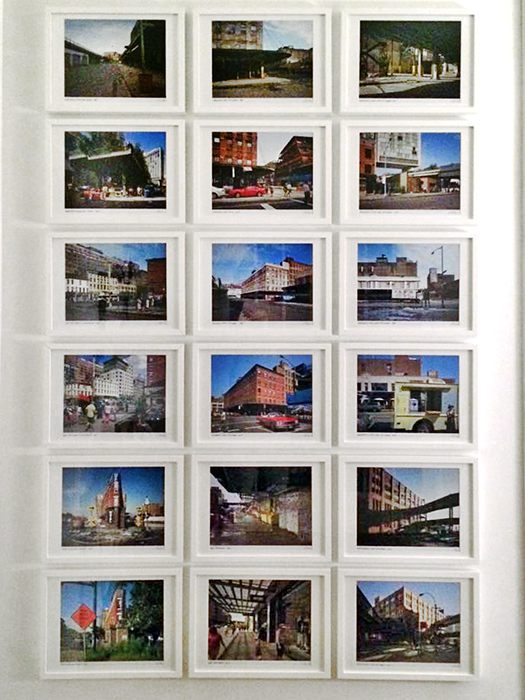

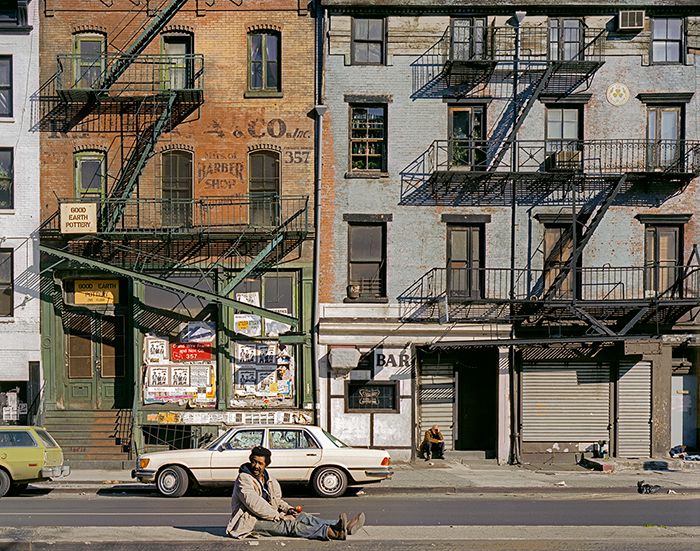

The Bowery near East 4th Street, 1980 — © Brian Rose/Edward Fausty

When I moved to New York in 1977, I lived on East 4th Street between the Bowery and Second Avenue. It was a relatively stable block compared to East 3rd, which was the location of a large homeless shelter with dozens of derelict men milling about in the street much of the day. The picture above was taken between 3rd and 4th Streets on he Bowery. Why it didn’t make it in my book Time and Space on the Lower East Side I can’t explain. Things fall through the cracks.

The buildings in the photograph are still there, relatively unchanged, but the facades have been cleaned up, and just to the right, there is a shiny new apartment tower with a 7-Eleven in the storefront. Why anyone goes there I can’t imagine since there are any number of better stocked bodegas and delis nearby. I guess the Bowery is 7-Eleven’s idea of a flagship location. It was a pretty rough scene in those days, and I have no intention of romanticizing its gritty authenticity. It certainly was authentic — and they were not serving Slurpees.

It was also a time of great creativity. CBGB was in the next block with the usual gaggle of black jacketed musicians out front, and lots of artists occupied lofts in or near the Bowery, the legendary end-of-the world skid row of New York. The apocalyptic nature of the neighborhood was both a scourge and an inspiration — at least it was for me. I wrote songs about the place, and of course, I photographed it.

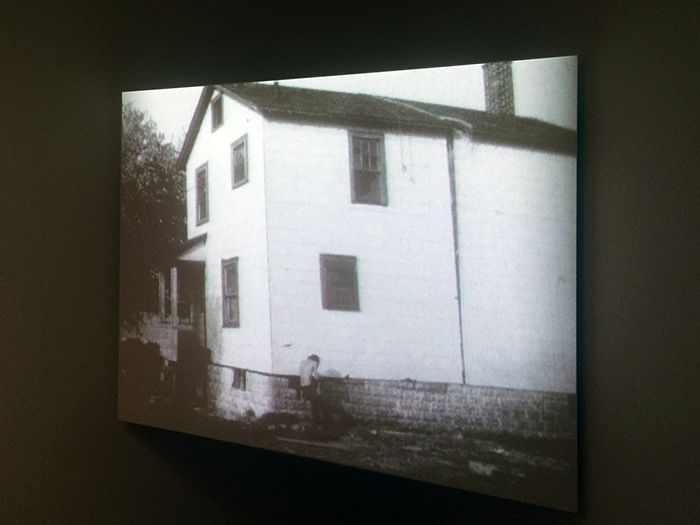

Brian Rose in 1980 — © Alex Harsley

Masking tape on camera to make it look less attractive to potential muggers.

The reality, however, looking at the photograph of myself above, is that we artists and musicians were to a great extent middle and upper middle class expats from the suburbs, products of America’s finest schools — and white. I was going to Cooper Union. Free tuition notwithstanding, it was an elite place, and you didn’t stumble in by accident. A recent article in Artnet News postulates that most successful artists come from relatively privileged backgrounds, and certainly, from my perspective, that is absolutely true. The starving artist is largely a myth, though no doubt there are easier and more reliable ways to make a living. And the other reality is that most artists are not doing fine art, either by necessity or by choice. They are in media, design, illustration, branding, advertising, commercial photography and film, etc. New York is full of these jobs — more now than ever.

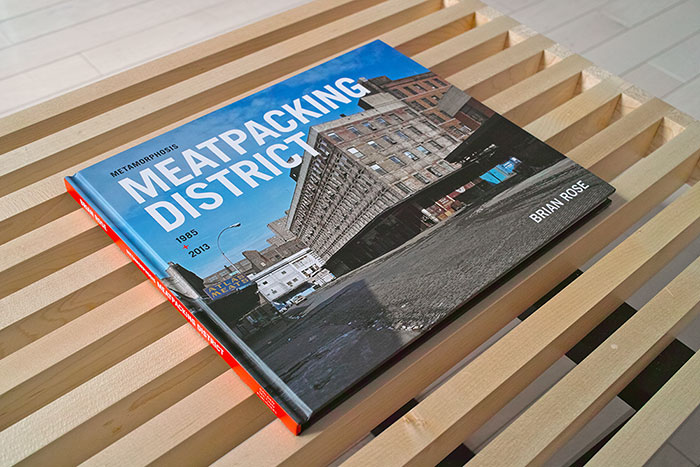

Going back to the Bowery and the Lower East Side of the 70s and 80s — art was not so much born out of the decay and poverty of the neighborhood, as it was the place we chose to make art, to reinvent ourselves, to run away from mom and dad, and for many, to waste time. It was cool, and a little dangerous. It helped that it was cheap — my parents had basically cut me off financially — and I often got by on pizza slices and falafel. When I graduated from Cooper, debt free, I began photographing the Lower East Side. But 4×5 film was bloody expensive, and I struggled to complete the project. One day, however, a check arrived in the mail — for $9,000 — which (looking it up) would be worth over $27,000 in today’s dollars. A relative had died and left me the money. It saved the day, and made the LES project a success. There was also a grant from New York State, and the Seagram Corporation bought a dozen prints for what would eventually become the collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture. The print sale happened because of a connection made at Cooper Union.

There’s nothing wrong with sudden windfalls or connections made in school, but let’s put aside the idea that artists are impoverished denizens of rotting neighborhoods. That’s not to say that gentrification has no impact on artists who need workspace to paint or create installations. It does. The truth is, however, that artists are entrepreneurs who calculate profits and expenses like everyone else — who network and negotiate — who create works that are often very expensive to produce. It helps to start with some money, and success breeds more success, fairly or not.

Do I still believe that art can express the highest aspirations of humanity? The deepest emotions? Can it still address the social and political issues of the day? Yes. That’s why I started, and why I’m still doing it.

But now, on to my next Kickstarter campaign.