Brian Rose 1974

Virginia Roots

I am a New Yorker, a self-identification that presupposes the likelihood that one may have come from somewhere else, from another state, or from anywhere in the world. My work as a photographer and musician emerged from the rubble and creative ferment of New York City in the late ’70s and early ’80s. But I was born and raised in Tidewater, Virginia, a place steeped in history, where English settlers in 1607 established a colony on the swampy shore of the James River, and the place where Africans first arrived on a Dutch ship as human chattel in 1619. The British surrender at Yorktown, 12 miles from where my family lived, effectively ended the Revolutionary War, and after the Civil War, Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, was imprisoned at nearby Fort Monroe, where my father worked at the end of his career with the army.

While it is possible to live in Virginia and remain relatively untouched by the existence of this powerful and ubiquitous backstory, that was certainly not the case for me. My family lived in Williamsburg, the former colonial capital, now a tourist destination, and as a child, the restored area with its manicured streets and gardens was my playground. It was a carefully buffed recreation of the 18th century suspended between reality and imagination, between document and myth. Ada Louise Huxtable, the architecture critic, once wrote: “What the perfect fake or impeccable restoration lacks are the hallmarks of time and place. They deny imperfections, alterations, and accommodations; they wipe out all the incidents of life and change.”

Brian Rose leading the Colonial Williamsburg Fifes and Drums, 1970

This ephemeral world – of neither here nor there – was, however, the actual location of my upbringing. I joined the fife and drum corps at nine years old, wore a costume with a three-cornered hat, and performed for thousands of visitors as well as two presidents of the United States. I attended church services with my father at Bruton Parish Church and was present at the noteworthy, but dimly remembered moment when Lyndon Johnson was challenged from the pulpit by our minister who called into question the president’s Vietnam policy. And when Nixon came to town for a conference, the fife and drum corps played patriotic tunes while protesters heckled from across the street. The church with its original 18th-century bell tower sat directly next door to the distinguished brick home of George Wythe, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and friend and mentor of Thomas Jefferson. Past and present were, improbably melded together, all of a piece. Yes, Williamsburg occupies a surreal performative space, but I came to understand that the kind of authenticity Huxtable pined for was, perhaps, a dubious concept in the meta-reality of modern America.

Colonial Williamsburg – © Brian Rose

Williamsburg, both the restoration and the present-day town, is dominated by its colonial-era trappings, but the Civil War’s lingering presence is never far away. There were earthen fortifications in the woods behind my house, weathered trenches, and I once found a metal uniform button hidden in the dirt. Richmond, the state and former Confederate capital, is only an hour up Route 5, a scenic two-lane highway that parallels the James River with its gracious tobacco plantations dating back to the 17th and 18th centuries. Richmond, during my youth, was a city struggling to preserve its image as a genteel southern capital. Middle-class whites were fleeing to the suburbs leaving an increasingly Black inner city, the cigarette companies had moved their plants out of town, and newly built freeways slashed through old neighborhoods and snaked through the industrial riverfront downtown. But the statues of Confederate generals loomed undisturbed on their pedestals along Monument Avenue, and the good old boys’ network carried on in the Jefferson Hotel and the Commonwealth Club. The South may have lost the war, but the honor of Robert E. Lee, the patron saint of the Lost Cause, remained undisputed.

Colonial Williamsburg – © Brian Rose

Despite the penumbra of history I lived under in Virginia, I felt oddly disconnected from the past on a more intimate level. In short, I had no grandparents. My father’s parents had died young, leaving him in the care of an older sibling, and on my mother’s side – it was less clear what happened. It seems that she had fled from an abusive home environment after graduating from high school at age 16, and never went back, never had any contact with her family. My father grew up on the southside of the James River among farmers and merchants in a small town surrounded by peanut and cotton fields not far from the scene of Nat Turner’s 1831 slave uprising. He once told me that as a child, he woke up in terror one night as a cross burned in their front yard. But he never provided any context for the story, any explanation for why they were targeted, apparently, by the Klan.

Captain John Smith statue, Jamestown, Virginia – © Brian Rose

Quite simply, I could not place myself mentally or physically in that landscape. It did not have anything to do with me, or so I believed. My father, in his own way, rebelled by leaving home to attend the University of Virginia. He was the first Rose to go to college. When my father died, my sister and I scattered his ashes in Gray’s Creek, a small tributary of the James River. We understood instinctively that the James was the central element of his life. The journey he had made from one side of the river to the other was not far as the crow flies, but it represented a more profound journey of personal renewal from country to city, from the old South to the new. My mother, always strong-willed and fiercely independent, with a statuesque bearing that made her seem taller than she was, vaguely used to talk about coming from broken down aristocracy – that it was all lost in the Great Depression she said – but there was no family to interact with, no one to confirm the story, and no homestead. I shrugged it off.

Over the years, I wondered about the history I never had, but I was determined to create a new identity for myself untethered to my Virginia roots. Like my father, I attended UVA, briefly studying urban design, and eventually graduated from New York’s Cooper Union. After school, I pursued a career focused on the documentation of cultural and historical landscapes. Most notably, I photographed the Lower East Side, the famous immigrant neighborhood of New York, and then in 1985 began photographing the Iron Curtain, the Berlin Wall, and the subsequent rebuilding of Berlin. In 2016, I responded to the unexpected and alarming election of Donald Trump by photographing Atlantic City with its ravaged streets and bankrupt casinos as a metaphor for America as a whole.

TrumpTaj Mahal, Atlantic City – © Brian Rose

In the spring of 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic swept across the country, hitting New York especially hard, and the city was placed on lockdown by Governor Cuomo. In March and April, I wandered through the neighborhood of Williamsburg, Brooklyn, its empty streets bare and frozen – as if time had stopped for my camera – keeping a safe distance from the few others who ventured out. I self-published a book called “Williamsburg: In Time of Plague,” marketing it on Kickstarter. And I used the quarantine time at home to begin investigating my missing Virginia roots on various genealogy websites.

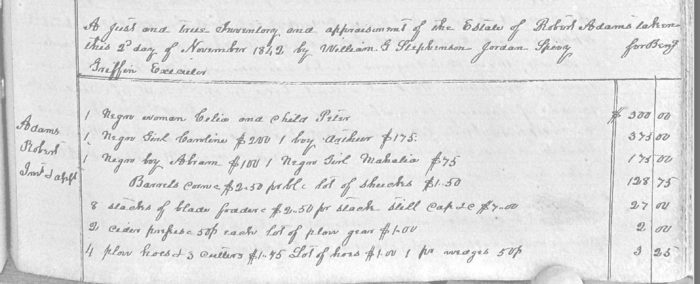

What I discovered left me dumbfounded. I peeled back the family’s layers on my mother’s side all the way to Jamestown – to the first supply ship that arrived in 1608, showing up just in time to save the few dozen colonists still alive but near starvation. One of those survivors was Temperance Flowerdew who married my 12th great grandfather, George Yeardley, the second royal governor of colonial Virginia. In 1619, fifteen of the first 25 enslaved Africans resided at Flowerdew Hundred, Yeardley’s plantation on the James River.

Another of my earliest ancestors may well have been present when Pocahontas and John Rolfe were married, an event that paused the ongoing war with the Indians, and a few years later, when the census of 1624 was taken, was found living on a plantation called Jordan’s Journey on the James River just south of Richmond. There were only 1,200 people of European descent in all of Virginia at that time. My later ancestors settled in Georgia and Mississippi – my 4th great-grandmother was a Creek Indian, and my 3rd great-grandfather died in the battle of Vicksburg fighting for the South. For unknown reasons, my grandparents migrated to Washington, D.C., and then back to Virginia. My immediate family ultimately ended up in a suburban-style ranch house on the outskirts of Williamsburg, precisely four miles from the excavations of the original fort at Jamestown.

Grays Creek, the spot where my father’s ashes were scattered – © Brian Rose

The Rose side of the family also traces its roots to Jamestown, to Surry County, directly across the river. My 7th great-grandfather, William Rose, settled in 1650 on the property adjacent to Smith’s Fort, land given to John Rolfe and Pocahontas by Chief Powhatan, precisely at the spot on Gray’s Creek where my sister and I had scattered our father’s ashes. It was as if we were all homing pigeons, somehow tuned to the way back, over centuries of time.

To a great extent, the revelation of this missing history was exhilarating, but it was distressing as well. These early Virginians were well-to-do planters, with much of their wealth derived from slave labor, not to mention that the land they claimed was essentially stolen from native people. At the same time, however, these first Virginia families were the catalysts for American democracy, and they espoused the enlightenment ideals that underpin the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, among the most remarkable achievements in western civilization. I still regard Thomas Jefferson’s UVA campus with its Roman Pantheon-inspired dome and classical colonnades as one of the greatest works of architecture in North America, an audaciously conceived beacon of learning perched on the edge of the Appalachian wilderness. This epitome of American idealism was built, however, largely by enslaved labor, and a circular granite memorial echoing the nearby Rotunda now acknowledges this integral and sobering fact.

The University of Virginia with my father, Leroy Rose

One of my great, great, great grandfathers was awarded 486 acres of land by Jefferson in appreciation for his service in the Revolutionary War. He was also, like Jefferson, the owner of slaves. And most remarkable was the story of my 3rd great uncle, who departed the Tidewater region of Virginia, like a Faulkner character, to set up a sugar plantation in Louisiana. His plantation, known as Hard Times, was in 1850 the most prosperous in the Mississippi Delta, with as many as 350 enslaved laborers working the fields and operating the sugar mill. The Civil War brought ruin and an end to the plantation economy. It did not, of course, do away with the racism underlying American society both in the South and the North. Not by a long shot.

In New York, the Covid pandemic continued, but the city’s crisis eased as people masked up and maintained social distancing. Donald Trump, unwilling to accept responsibility or listen to the advice of experts, recklessly encouraged Americans to shop, eat out, and carry on as usual as the death toll from the virus mounted across the country. Then, on May 25th, George Floyd, a Black man living in Minneapolis, was killed by a white police officer while under arrest for allegedly passing a counterfeit $20 bill. The next day a cell phone video of Floyd’s arrest was made public, the officer’s knee pressing against his throat, his gasping, repeated last words, “I can’t breathe.” The video went viral, sending shockwaves through the body politic, shattering the preternatural calm of the pandemic’s previous two months. Protesters took to the streets in Minneapolis and were met by tear gas and rubber bullets. Over the following weeks, millions throughout the U.S. marched against racism and police violence, and “Black Lives Matter” became a rallying cry taken up by a diverse cross-section of the public.

BLM protest, Williamsburg, Brooklyn – © Brian Rose

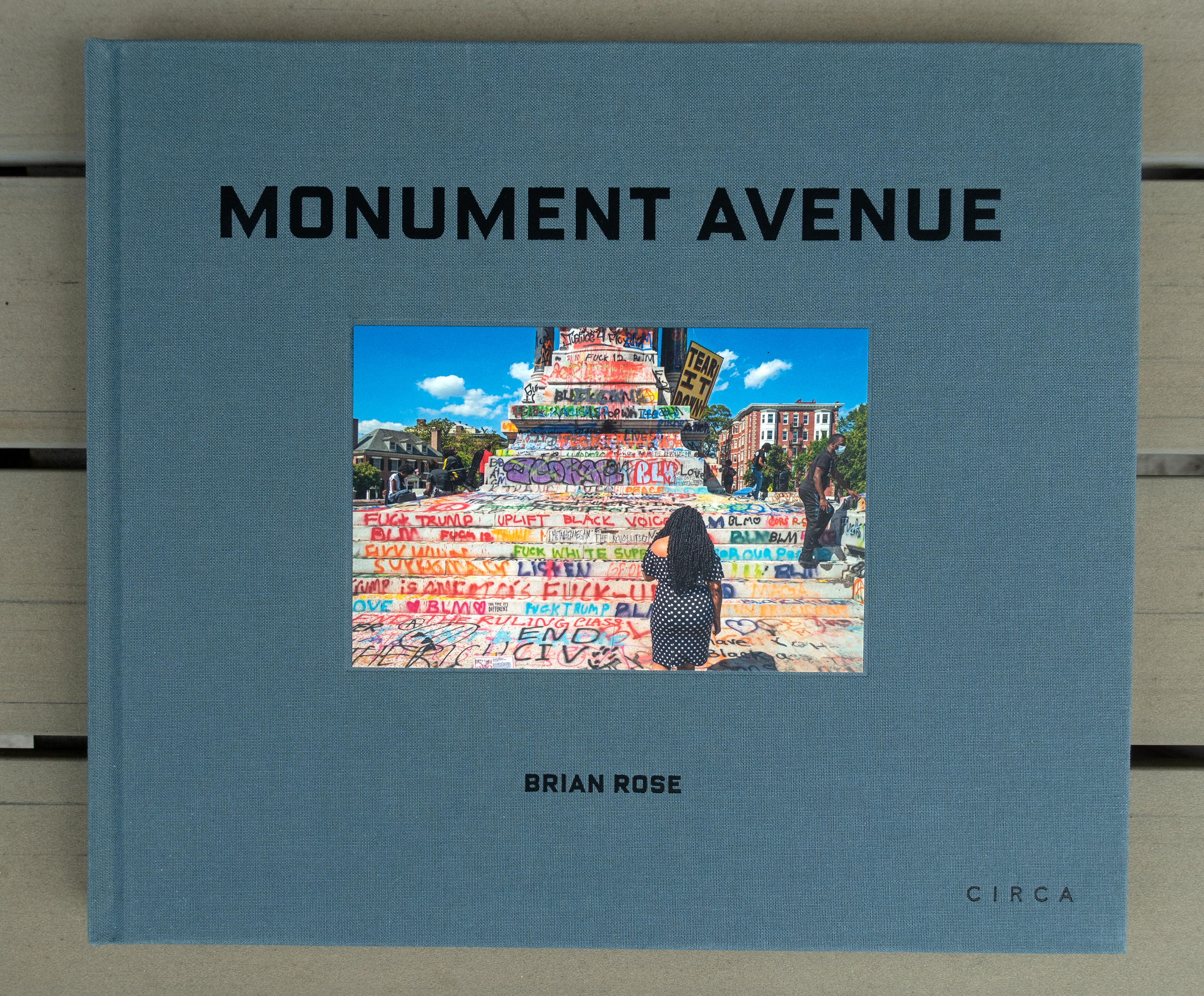

In Richmond, demonstrations focused on Monument Avenue with its statues of generals and other Confederate luminaries. These stolid ghosts of the past were suddenly reanimated in the passion of the BLM movement, and the longstanding debate surrounding these totems of the Confederacy – whether they should be removed or maintained with some sort of historic contextualization – now appeared moot. In early July, it became clear that the end of the road was approaching for Monument Avenue. On July 10th, protesters pulled Jefferson Davis from his pedestal, and two days later, I drove down to Richmond to document the last days of the grand boulevard of the Lost Cause.

Jefferson Davis Monument, Monument Avenue – © Brian Rose

In traveling to Richmond, I should point out that I have not been a total stranger to my home state since moving to New York. Over the years, I made dozens of trips to visit my parents, rendezvoused there with my sister who flew in from San Francisco and on several occasions marched down the Duke of Gloucester Street with the alumni of the Colonial Williamsburg Fifes and Drums. But this time, it felt different. I was on a mission to repossess, on my own terms, my birthright and heritage. It was not about atonement for a history I was not responsible for, but it was about seizing the moment when the past connected to the present in a circle of time, memory, and place. It felt purposeful, conscious, and I could see arrayed before me a palimpsest of genetic code and geography, like a map, like personal destiny revealed.

J.E.B. Stuart pedestal, Monument Avenue – © Brian Rose

As I stood on Monument Avenue in the low winter sun surveying the pedestals that once elevated J.E.B. Stuart and Stonewall Jackson above the crowd, and the brazenly, triumphantly, desecrated plinth of Robert E. Lee, I thought about how American democracy had nearly collapsed in a tawdry display of banner-waving, cult-like allegiance to a wannabe dictator, in a spasm of racial animus. Our better angels prevailed, just barely. We are left now with empty pedestals on Monument Avenue and a sense of loss. Not, of course, for the bronze idols promoted by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, not for the Lost Cause. And certainly, we can learn to accept, though not excuse, the imperfections of the Founding Fathers, men of their time, who arrived at Jamestown and sought to create a new world. But there is loss, nevertheless, for the pantheon of heroes we once revered, their icons now toppled or tarnished, and there is the corresponding loss of ideals displaced by voices of demagoguery and bigotry. We are left with empty pedestals on Monument Avenue as the sun comes up and I point my car north on I-95 back home to New York City.