Jefferson Davis grave, Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia — © Brian Rose

I grew up in Williamsburg, Virginia, the one time colonial capital, and now restored town. It’s a place steeped in history, a place that played an important role in the founding of the United States, and I lived just a few miles away from Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America. My ancestors can be traced back to the south side of the James River, and at least one Rose came aboard one of the first ships to Jamestown. Not far away is Yorktown, where the last major battle of the Revolutionary War took place, and it appears that my great, great, great — I’m not sure how many great — grandfather fought and died in that war.

On my mother’s side of the family, I have equally deep American roots. The Berryhills emigrated from Scotland to North Carolina, and some of them headed south to Georgia, marrying into the Creek Indian tribe, which was driven west in the “Trail of Tears.” Despite this Native American heritage, my Berryhill line was clearly white, though my sister and I used to joke when we were kids, that we had slightly asiatic features. That was long before we had any idea that there might be a reason.

Some time before the Trail of Tears, my family traveled from Georgia to Mississippi and settled in the area around Jackson, named for President Andrew Jackson, who, ironically, is responsible for vanquishing the Creek Indians from their homeland. My ancestor Alexander Berryhill was a corporal in the Confederate Army and died in the battle of Vicksburg. His grandson eventually made his way to Richmond, Virginia, and finally to Portsmouth, Virginia, where I was born.

Berryhill marker, Vicksburg, Mississippi

Growing up in Virginia the symbols of the old South were ubiquitous, and I was accustomed to seeing the Confederate flag displayed, sometimes in official settings, but more often in an ad hoc fashion, as a statement I usually associated with red neck no-nothingism, or a solidarity with suspect southern values, one of which was racism. On the other hand, I knew a number of people who participated in Civil War battle reenactments in which the flag was integral, and although it isn’t my kind of thing, I’ve always understood the way in which both sides in the “War Between the States” were given equal respect. That was what I grew up with correct or not — that Robert E. Lee surrendered with honor at Appomattox — that the South may have been wrong, but it is our heritage, and is part of the history of who we are as a nation today.

So, I am a descendant of families that came to Jamestown, fought and died in the Revolution, married into the Creek Indians, and fought and died in the Civil War. My father once told me that my grandfather was a Republican, which was the party of Lincoln in the old South, and he said that he woke one night to the spectacle of a cross being burned in the front yard. I left the South to make my home in the Yankee city of New York, and lived for 15 years in Amsterdam, among the people who founded that city, New Amsterdam..

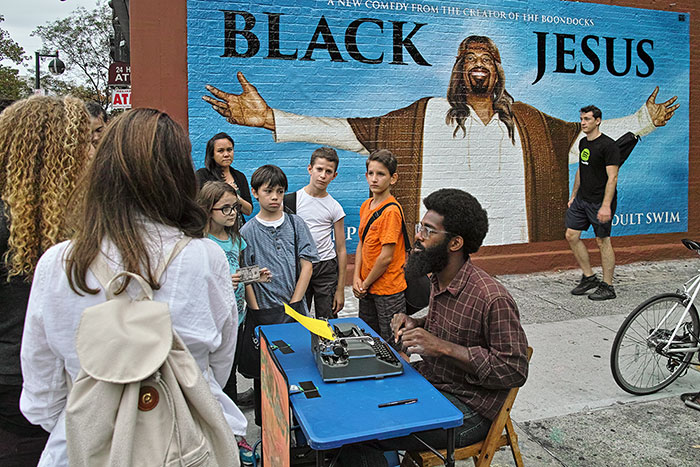

Jefferson Davis and Confederate flags, Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia

© Brian Rose

Recently, I returned to Richmond for a funeral in Hollywood Cemetery, the gravesite of Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy, and the burial ground for 18,000 Confederate soldiers. There were visitors to Davis’s monument, tourists, or perhaps, those who venerated what he represented — I don’t know. And there were Confederate flags. Seeing the flags sent a chill through me on that already cold November day. The Stars and Bars as historical object is one thing, but when flown, (with a calculated impunity) is something else.

Let us remember those who died, right or wrong, in the Civil War. Let us show respect for that history as we seek to learn from it. But it is long past time for the Confederate Flag to fly over any capital in any state, and it is time to acknowledge, finally, that what is a symbol of heritage to some, is clearly a symbol of hatred to others. And as such, should be relegated to museums and text books once and for all.