Place Saint-André-des-Arts, c. 1865 — Charles Marville

Place Saint-André-des-Arts, c. 1865 — Charles Marville

I went to the Metropolitan Museum last weekend to see the Charles Marville show, the photographer who documented Paris during the time of urban planner Baron George-Eugène Haussmann. Haussmann, under the supervision of Napoleon III, razed large sections of the old city in order to create the grand boulevards and monumental squares and traffic circles we associate with contemporary Paris. Photography was still new — only two decades old — when Marville was commissioned to photograph the transformation of Paris. And today, 180 years since the invention of photography, the documentation of the urban environment remains an essential and vital focus of the medium.

Boulevard Henri IV (de la rue de Sully) (fourth arrondissement), c. 1877 — Charles Marville

Boulevard Henri IV (de la rue de Sully) (fourth arrondissement), c. 1877 — Charles Marville

I was familiar with Marville prior to seeing the exhibition, but not in great depth. The inspirational touchstone for me was always Eugène Atget, who also photographed Paris with a large format camera. I have always found Atget’s work central to my understanding of what documentation could be — that even the most clear-eyed description of place can evoke emotion and mystery. Marville, however, is Atget’s immediate predecessor, and as such, progenitor to all of us who make architecture and the urban landscape our subject.

Entrance to the École des Beaux-Arts, c. 1870 — Charles Marville

To Marville and his contemporary audience, I can imagine that everything recorded by the camera was new and wondrous. The organized elegance of Marville’s compositions belies his training as an artist, and appears almost modern to our eyes. But Marville was not employing today’s self-conscious visual strategies. He was a pioneer discovering the medium of photography while simultaneously carrying out his commission to photograph the changing visage of Paris. It was the beginning of a long violent transfiguration initiated by Haussmann, the great destroyer and creator of the City of Lights. And indeed, some of Marville’s most architecturally precise images show the newly designed gas lamps that brought that light into the heart of the formerly dark medieval city.

Top of the Rue Champlain, 1877-78 — Charles Marville

Top of the Rue Champlain, 1877-78 — Charles Marville

Old Paris is gone (no human heart

changes half so fast as a city’s face)…

There used to be a poultry market here,

and one cold morning… I saw

a swan that had broken out of its cage,

webbed feet clumsy on the cobblestones,

white feathers dragging in the uneven ruts,

and obstinately pecking at the drains…

Paris changes . . . but in sadness like mine

nothing stirs—new buildings, old

neighbourhoods turn to allegory,

and memories weigh more than stone

A translation of The Swan by Charles Beaudelaire

In the New York Times, Michael Kimmelman writes about Paris: “An architecturally harmonious capital rose from the rubble, a city of spectacle, built for a new, modern economy, but homogeneous and no longer welcoming to many of the poor souls who had helped make the place run and had always been deep in its cultural lifeblood.”

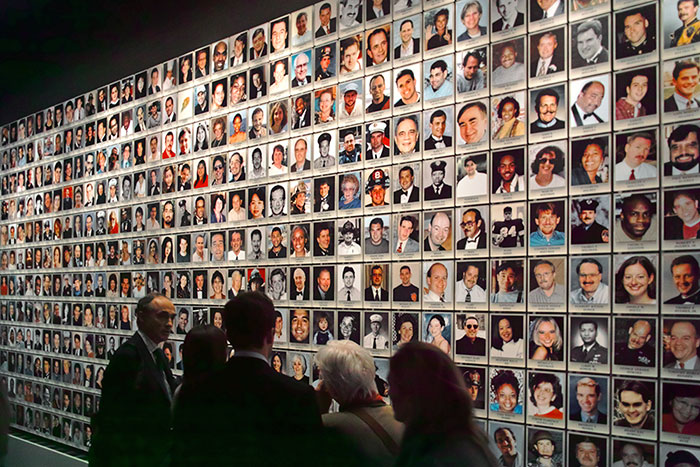

Some of the same dynamic is taking place in New York City, though without the wholesale physical destruction of Haussmann or New York’s own Robert Moses, who leveled neighborhoods to create his parks and parkways. But what has happened in Manhattan represents a dramatic shift of capital back to the center city from the periphery where it fled in the ’60s and ’70s, and Manhattan has increasingly become a safe parking place for vast sums of foreign money. No, there were no visionary utopians like Haussmann or Moses this time, but there was Michael Bloomberg, businessman extraordinaire, who took up the reins of a city reeling from the devastation of 911 and set the city on its present track.

Drilling of the Avenue de l’Opéra — Charles Marville

Drilling of the Avenue de l’Opéra — Charles Marville

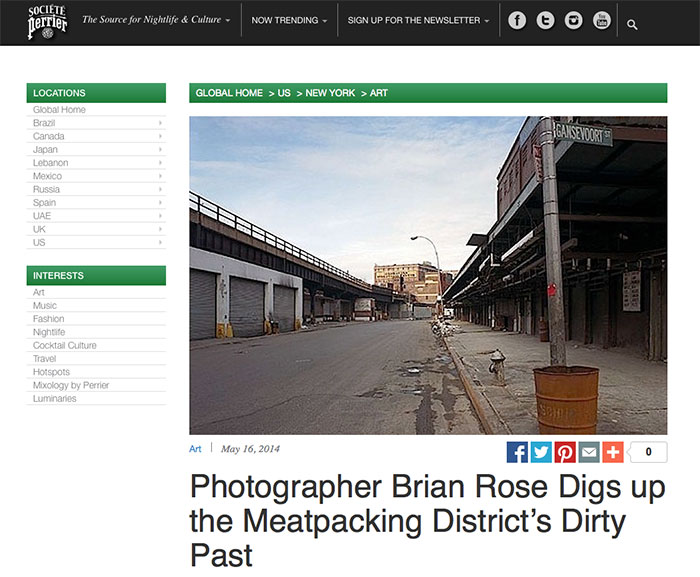

Kimmelman also writes: “I wonder, here in the early third (millennium), whether photographers are now out and about, in the spirit of Marville, documenting 57th Street, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Bushwick and East Harlem, Willets Point, Long Island City and Hell’s Kitchen. Big cities change. That’s urban life. But the best cities don’t leave the vulnerable behind.”

At least some photographers are out and about, despite a trend these days toward staged reality and the ultimate myopia of selfies. I’m certainly out and about. And the vulnerable citizens of this ever changing metropolis ride the jammed subways day and night commuting to and from increasingly far flung quarters of a city that still attracts immigrants from around the globe. Where this all leads — all this constant motion — all this restless energy — I have no idea. But the spirit of Marville remains alive among contemporary photographers, and the visual history of these times will be preserved.

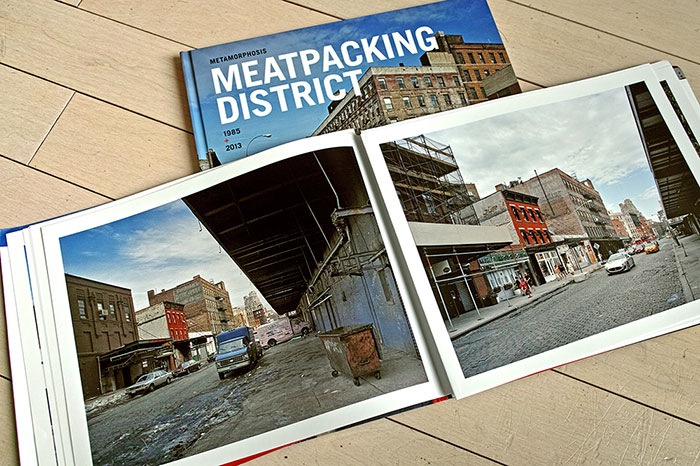

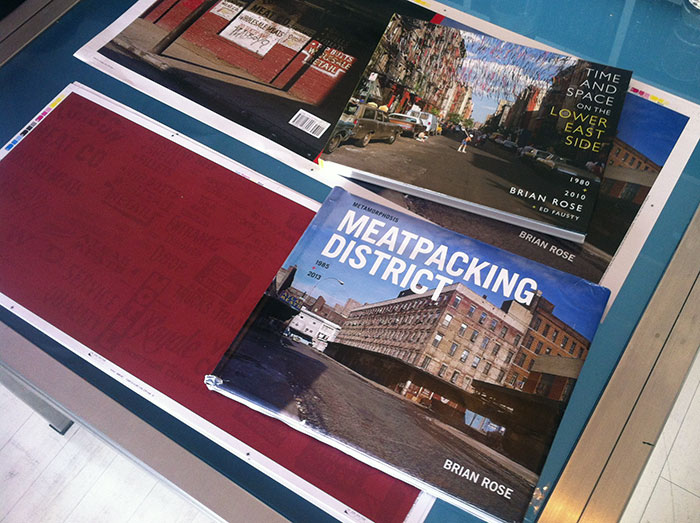

Metamorphosis F&Gs — © Brian Rose

Metamorphosis F&Gs — © Brian Rose

Photograph by Vivian Maier — From Liberty Island looking toward Ellis Island

Photograph by Vivian Maier — From Liberty Island looking toward Ellis Island Untitled by Vivian Maier

Untitled by Vivian Maier

Place Saint-André-des-Arts, c. 1865 — Charles Marville

Place Saint-André-des-Arts, c. 1865 — Charles Marville Boulevard Henri IV (de la rue de Sully) (fourth arrondissement), c. 1877 — Charles Marville

Boulevard Henri IV (de la rue de Sully) (fourth arrondissement), c. 1877 — Charles Marville

Top of the Rue Champlain, 1877-78 — Charles Marville

Top of the Rue Champlain, 1877-78 — Charles Marville Drilling of the Avenue de l’Opéra — Charles Marville

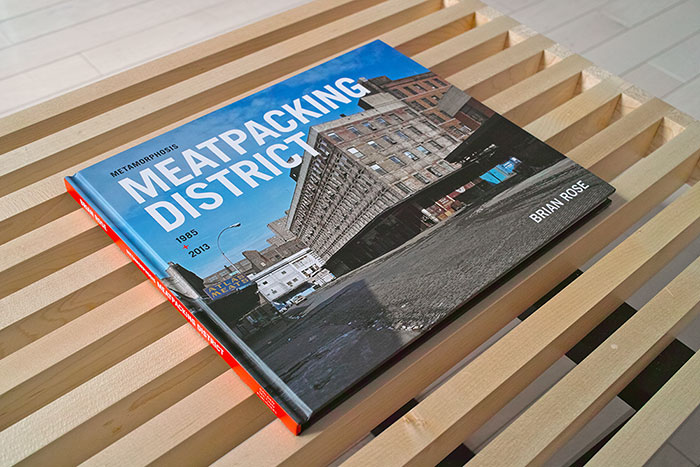

Drilling of the Avenue de l’Opéra — Charles Marville Metamorphosis: Meatpacking District 1985 + 2013, back cover image — © Brian Rose 1985

Metamorphosis: Meatpacking District 1985 + 2013, back cover image — © Brian Rose 1985 Cover mockup of Metamorphosis: Meatpacking District 1985 + 2013

Cover mockup of Metamorphosis: Meatpacking District 1985 + 2013