Yoko Ono’s campaign against tracking.

The ghost of Peter Cooper — © Brian Rose

The ghost of Peter Cooper — © Brian Rose

Cooper Union students have taken over President Jamshed Bharucha’s office in the Foundation Building on Cooper Square. They are demanding his resignation in response to the decision made by the board of trustees to begin charging tuition at one of America’s last free colleges.

The president and the board of trustees have failed in their stewardship of this magnificent institution. May the ghost of Peter Cooper forever haunt their dreams.

Sign the no confidence letter here.

New York Times article from this morning.

14th and Hudson Street, 1985 — © Brian Rose

14th and Hudson Street, 1985 — © Brian Rose

14th and Hudson Street, 2013 — © Brian Rose

14th and Hudson Street, 2013 — © Brian Rose

A few months ago I posted some of my photographs of the Meatpacking District taken in 1985. At that time, the area was desolate by day–the city seemingly abandoned. People have been clamoring for me to do before/afters of the images, and I have more or less decided to go ahead with it, even though it was an approach I largely eschewed when doing Time and Space on the Lower East Side. The changes in that neighborhood were much more complex and deserved a more nuanced investigation. But here in “MePa” the transformation of the streetscape is so gobsmacking that it just seems a necessary thing to do. So, the plan is to repeat about dozen of the images made in ’85, and do various other contemporaneous views as they strike my fancy.

Yesterday, I was on 14th Street with my point-and-shoot camera and made the picture above. Soon, I’ll get out there with my view camera.

Staten Island Ferry terminal in Manhattan — © Brian Rose

Staten Island Ferry terminal in Manhattan — © Brian Rose

Now that my exhibition is down, and Time and Space on the Lower East Side is about 2/3 sold, it’s time to shift gears to my next book, another long-term project dealing with New York City. A couple of years ago it occurred to me, almost out of the blue, that I had in my archive enough photographs taken over the years for a book about the World Trade Center. This was not a premeditated project, but something that grew organically, one series of images at a time.

You can see the book dummy here on Blurb. And here is the CNN story about it. The mural based on seven close-up images of the Twin Towers’ facades can be seen here.

Most of the book is done. It’s just a matter of pulling it together with several images of 1WTC reaching its full height on the skyline, and possibly a few more thematic images that act as connective tissue. Awhile ago I did a walking tour through the St. George area of Staten Island and came across a mural of the Twin Towers and firefighters. I snapped a couple pictures with my pocket camera. On Saturday I went back with my view camera. As is so often the case, the whole situation seemed different–different light, different atmosphere, vehicles blocking some of the sight lines to the wall. But you never know about these things. I found other ways to photograph the same subject. I’ll post the results when the film gets developed.

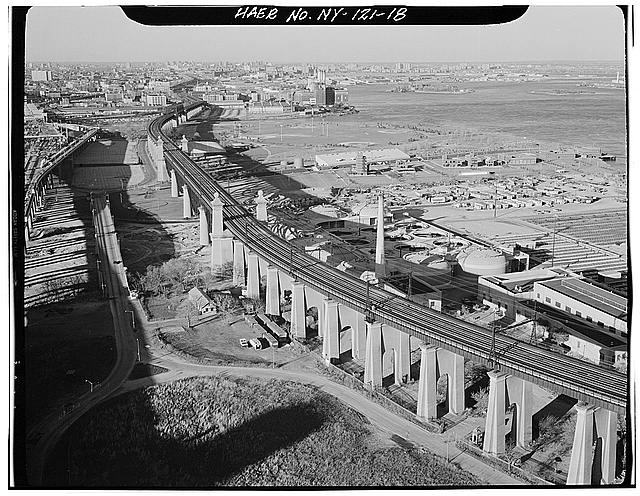

Randalls Island rail viaduct — © Brian Rose

My son Brendan plays baseball with his middle school team and little league. Fields are hard to come by in Manhattan, and those that are available are usually artificial turf, oddly shaped, and somewhat difficult to get to. This year, we’ve had to go up to Randall’s Island several times. It’s a mess to get to by public transportation. Situated in the East River adjacent to Harlem, it has historically been a place to hide things like psychiatric hospitals and sewage treatment plants. Recently it has become a recreational park with, track and field, tennis, soccer, and baseball facilities.

Randalls Island is crisscrossed by major transportation infrastructure, the Triboro Bridge, famously built by Robert Moses, and the Hell Gate bridge that carries Amtrak and freight trains into and out of the city. The massively built structure passes over the entire island and a bicycle and foot path runs beneath the arches. Here’s an aerial view made some years ago:

As a proud alumnus of Cooper Union, I write the following post with the heaviest of heart.

The quotes below come from the New York Times March 9, 1904, in a tribute to Peter Cooper, during which Andrew Carnegie and others expounded on the responsibility that comes with great wealth. The director of Cooper Union, Charles Sprague Smith, spoke as well honoring the gift of $300,000 by Carnegie that made Cooper debut free “from basement to roof.” He went on to honor Abram Hewitt, son-in-law of Peter Cooper, former mayor, and father of New York’s subway system: “I know that the supreme desire of his life was that Cooper Union should be free. Every part of it is now free in every sense.”

It is no longer.

The values espoused eloquently in 1904 — albeit in self-congratulation — have now been repudiated by the decision of the board of trustees of Cooper Union to charge tuition beginning in 2014. Those who have guided this institution in recent years have failed in their trusteeship of this treasure of New York and the nation.

As I wrote in an earlier post, Cooper Union is too small, too specialized, to survive in direct competition with larger better-funded institutions. The fact that it was a full scholarship — free — college put it in a class by itself. It brought the best students and professors together in an egalitarian community unlike any other in the world.

That unique community of intellect and creativity has been sacrificed. Unless another Andrew Carnegie comes to the rescue quickly, or some other scheme is devised to return the school to its former mission, Cooper Union, in its now comprised state, will not likely survive.

Norfolk Street, Lower East Side — © Brian Rose

Norfolk Street, Lower East Side — © Brian Rose

I was in Boston Thursday evening when the marathon bombers ran amok. Well… not physically. But I witnessed the events as they unfolded in a most unexpected, vividly surreal way.

I was fascinated by the attempts of the public to find the bombers amidst the crowd near the finish line of the Boston marathon. Amateur sleuths were reviewing dozens of photographs available on the internet, engaged in a real-life version of “Where’s Waldo,” except that Waldo wasn’t in red and white stripes. He, and his likely accomplice, were supposedly carrying black and silver backpacks big enough to contain pressure cooker bombs.

The crowd source detectives had managed to identify a number of suspects, all innocent as it turned out, and the New York Post had run one of the photos on their front page essentially fingering two young men in the crowd as the bombers. They were the wrong guys. Adding another black mark — if it’s even possible — on the shameful record of Rupert Murdoch’s odious tabloid. On Thursday the FBI cleared things up by releasing video and photographs of the actual bombers who were still at large.

I wanted to see how things were playing out on Reddit, the social media site with a group actively combing through the Boston crowd photos. It was after 9pm and I was reading the comments on Reddit, when suddenly, someone wrote that the bomber’s address had just been given out on the Boston police scanner. I tuned in, which is easily done on the internet, and began listening to the mostly tedious back and forth between police officers and dispatchers. Though nothing more came up about the address, for some reason I kept listening while continuing to read commentary about the photos.

At around 10:30 an anguished voice punctuated the static — “officer down!” — and then a few minutes later I heard the strangled cries for help from the MIT campus in Cambridge. Having no idea that it was related to the marathon bombers I continued to listen as the police rushed to the scene and began searching the subway and the surrounding streets. It was obvious that something dramatic and highly unusual had occurred in this normally placid college town.

And then, a short time later, the initial report of a carjacking, the pursuit of the stolen car, “shots fired, shots fired,” explosions, calls for “long guns” and “gold cars.” It was pandemonium, as one police cruiser after another notified dispatch that they were headed for the scene. I listened deep into the night as the police began setting up a search perimeter and a command post. By then, it was clear that the carjackers were indeed the fugitive bombers, and I went to bed knowing that one of them was dead and the other at large in Watertown, the community adjacent to Cambridge.

None of this raw and riveting information came from TV news or the websites of major media like the New York Times. I was one of a relatively small number of people — tens of thousands certainly — but small in country of over 300 million who witnessed in real time the dramatic events of that evening, listening through the cross talk, the cryptic jargon, the Boston accents, unfolding on the police scanner.

There will be a lot of discussion about how things were handled — to my ears, the police were amazingly calm and professional under the most extreme circumstances — and whether we, the public, should be permitted to hear things from the inside in the future. For me, it was a unique, unforgettable experience, unfiltered by the bobble heads of TV news. I’m still thinking about it, but my initial feeling is that having access to the police scanner was more help than hindrance.

I was there.

The Seagram Building (375 Park Avenue) — photo by Ezra Stoller

A few days ago the Times ran a story about Phyllis Lambert’s book Building Seagram, which tells the story of her role in the selection of Mies van der Rohe for the commission. The Seagram Building (now 375 Park Avenue) is regarded by many as New York’s finest skyscraper of the modern era. Lambert was the daughter of Samuel Bronfman, the head of Seagram, and her zeal for architecture and civic responsibility led her to take up the cause in New York and in her hometown of Montreal. It may sound unlikely, but there is a small connection to Time and Space on the Lower East Side in this story.

In the late 70s at Cooper Union, one of my professors was Richard Pare, who at the time was assembling a collection of architectural photographs for Seagram under the direction of Phyllis Lambert. Those photographs, acquired by Pare, from all over the world, would eventually comprise a unique part of the collection of the Canadian Center for Architecture, another Lambert initiative. Soon after graduating, I began the Lower East Side project with Edward Fausty. After a number of months of work — once we had gotten some momentum going — we contacted Pare and showed him our pictures.

I remember visiting Pare in the Seagram Building on Park Avenue in 1980 bringing a box of 11×14 prints. We eventually sold a dozen or so prints to Seagram, which helped fund the project at a critical time when our money was running low. I also remember meeting Lambert, and attending an event honoring Berenice Abbot, the great photographer of New York City. I’m not sure I appreciated her importance until then.

There were several key funding moments that made the Lower East Side project possible — a New York State CAPS grant (similar to today’s NYFA grants), an unexpected windfall of $10,000 left to me by a deceased relative, and the Seagram/Canadian Center for Architecture purchase. Without those three sources of money, it’s doubtful that the Lower East Side project would have been completed, and my career — such as it is — launched.

Thank you Phyllis Lambert — and Richard Pare.

OMA’s (Rem Koolhaas) public library in Seattle, a fixture of downtown, now almost ten years old. I had seen photographs, which were impressive, but having been disappointed by some of Koolhaas’s buildings in the past, I wanted to see this one in person. The exterior is a bit jarring–wedged tightly into a difficult sloping site–like the nearby city hall. But its origami-esque planes make it a strong, if impersonal, sculptural form, next to the comparatively fussy civic building by Bohlin Cywinski Jackson. Inside, there are familiar Koolhaas concepts like the continuous ramp linking the different levels of book stacks, and the industrial metal egg crate railings and cheesy padded acoustic panels are materials he’s used elsewhere. What’s different, however, is the drama of the interior spaces–at times vertigo inducing–but tightly controlled and organized conceptually. What was great was to see this most challenging architectural environment full of people, using it comfortably, reading, lounging, working on computers. But Koolhaas’s buildings never sit cozily, nor play by the rules. Certainly not this one.

Here are some snapshots taken with my point-and-shoot.