Smith Tower, Seattle — © Brian Rose

Smith Tower, Seattle — © Brian Rose

On the road. Not much time for comments. Smith Tower, once the tallest building on the West Coast. Still a gem.

A time out from my Lower East Side book and exhibition.

My photographs of the former Iron Curtain and Berlin Wall are currently featured in the journal MAS Context. To quote their website, MAS Context, a quarterly journal created by MAS Studio, addresses issues that affect the urban context. Each issue delivers a comprehensive view of a single topic through the active participation of people from different fields and different perspectives who, together, instigate the debate.

The photographs shown begin in 1985 when I first began traveling across Europe with the view camera documenting the landscape of the Iron Curtain and come forward to a few years ago when I was last in Berlin. I have continued to photograph the area where the Wall once ran through the city. Although the border zone has become less visible over the years, there are still moments of urban disjuncture, as well as historical markers, remnants of the Wall, and the presence of new architecture and monuments.

In the last picture of the series, an East German Trabant, the iconic mini car, hovers from a video screen next to the Brandenburg Gate.

Jason Eskenazi, a photographer, worked for a time as a security guard at the Metropolitan Museum. For two months in 2009 he arranged to get himself assigned to the galleries housing the exhibition based on Robert Frank’s seminal book The Americans. As he recognized photographer friends visiting the show, he began querying them about the images from the book that meant most to them. After quitting his job, he continued to reach out to photographers, some well-known, most not.

The result is a compendium of these short commentaries printed without images entitled The Americans List. It is necessary to know The Americans, or to have the book handy, while perusing this slender little volume, but most photographers have seen and assimilated Frank’s work at some level. Most have at least one image that stands out for them, and I am no exception.

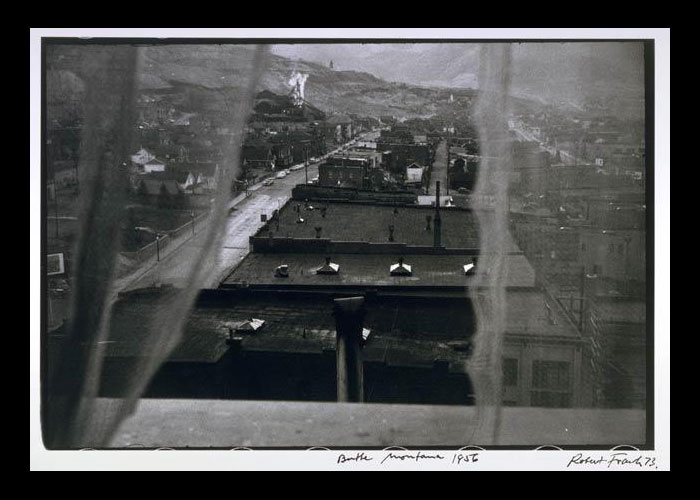

View from hotel room window, Butte, Montana, 1956 — photograph by Robert Frank

I think of Robert Frank’s The Americans as a road film that takes us sweeping across the landscape from one scene to another, a series of glimpses, anecdotes, gestures, faces, places, jump cuts, disjunctions, jarring, restive movement from one point to the next. There is no story, but thousands of possible stories.

View from hotel window, Butte, Montana:

I wake up from a dead sleep. Can’t tell what time of day, the light dull, the air thick with copper dust, the distant growl of machines. They are digging, devouring the earth, and they’d gladly eat the town alive if they could, human bodies and their thrown-up shelters and shops, inconvenient constructions, in the way of the divine right of power, of electricity speeding through wires.

I am traveling, on the run to be honest, took the car, left my wife behind. I am standing naked in the window staring through the flimsy curtains at the dark sullen town. It’s the end of the world. But I’m happy. I’m free — for the moment.

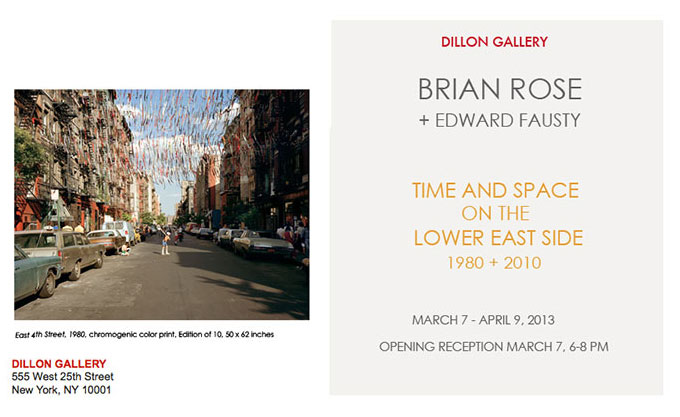

Time and Space on the Lower East Side at Dillon Gallery — © Brian Rose

It took much of the afternoon Wednesday to lay out the show and get the frames up, but I already had a pretty good idea where I wanted things to go. The opening Thursday evening was well attended, despite wintry weather, and it was great to see lots of old friends and meet new people. Ed Fausty who collaborated on the 1980 pictures was there as was Suzanne Vega, who wrote the foreword of Time and Space along with music friends, Frank Mazzetti and Norman Salant. Bill Diodato, my publisher, was there along with Warren Mason, who designed Time and Space.On the photography side, my friend and mentor, architectural photographer Cervin Robinson was there, and Mark Jenkinson, fellow Cooper Union grad, and Jan Staller, another color photographer who goes back to the late 70s and is still doing strong new work. Very pleased to see Sean Corcoran, the photography curator from the Museum of the City of New York. And it was particularly nice to have my painter friend Tim Raymond down from Buffalo.

I’m leaving out lots of people, but I’m appreciative of everyone who made this a festive occasion on an otherwise “dark and stormy night.” And thanks especially to Valerie Dillon for making it all possible.

Did anyone take pictures? I don’t have a single image from the opening.

Time and Space on the Lower East Side at Dillon Gallery — © Brian Rose

Cooper Union, Foundation Building — © Brian Rose

I have not previously weighed in on the controversy embroiling my alma mater The Cooper Union, one of the most prestigious and historic schools in America. I read the paper, I look at websites, and hear things, but I have no inside track on what is going on. What I do know is troubling, and I believe the school’s viability is in grave danger.

In a nutshell, Cooper was founded by the industrialist Peter Cooper as a school for art, architecture, and engineering that was affordable for all regardless of ability to pay. It was located, appropriately, on the edge of the teaming Lower East Side, and for decades it has been tuition free. One of the few all scholarship institutions of higher learning in the world. Many of its graduates are now leaders in their respective fields–and have a particularly important impact on New York City.

Due to hard economic times, mismanagement, and the growing cost of higher education, Cooper finds itself in financial trouble. The board of trustees is about to make a momentous decision on whether to charge tuition possibly ending the school’s unique charter as stated by Peter Cooper to be “open and free to all.”

With regard to the art school, should the board decide on charging tuition, Cooper will then have to compete head-to-head with several highly esteemed art schools in New York City, as well as many other fine schools around the country. Cooper’s strength has always been the quality of its students–astonishingly bright and talented–the best of the best chosen without regard to ability to pay. Cooper’s facilities, two architecturally outstanding buildings notwithstanding, are meagre compared to other art schools. Cooper, being a small school, has fewer course offerings than others, and its faculty, while outstanding, is equal to those who teach elsewhere, but not necessarily better.

Charging tuition will end the uniqueness of Cooper Union and place the school at a competitive disadvantage. It will no longer be the most sought after art school in the city. The best students will choose schools with more to offer for their money. The money raised from tuition on a mere 1,000 students will not ultimately solve other structural financial problems. A death spiral is possible, if not likely.

A way has to be found forward that will retain Cooper’s unique tuition free status. The principles espoused by Peter Cooper must be reestablished, and the school should embark on new fund raising efforts. Those of us who do not have much money to give, do have our work, which could be leveraged to raise money. The art alumni need to be engaged, not simply asked for pledges. While doing my Kickstarter campaign last year to fund my book, I thought about how Cooper might undertake a similar campaign, except on a much larger scale, using the work of alumni as rewards for donations. Forget phonathons and other outmoded fundraising models.

It’s not just about money–it’s about engagement. A sense of belonging and responsibility. Should the board choose for tuition, many alumni will walk away, and that will be the beginning of the end.

Time and Space on the Lower East Side featured in the New York Times. It will run in the print edition of the Metropolitan section of the Sunday Times and online.

Exhibition opens this Thursday:

Dillon Gallery

555 W25th Street

New York, NY 10001

March 7 – April 9

Opening Reception, Thursday 6-8pm

West Street (West Side Highway) and West 10th Street, Greenwich Village — © Brian Rose

Bedford Avenue, Williamsburg, Brooklyn — © Brian Rose

Two random photographs walking around town. A few thoughts about movies and photographs.

There are three movies up for Best Picture in the Academy Awards this weekend that have created a swirl of controversy about truth and the telling of stories based on real events. Lincoln by Steven Spielberg will likely walk away with a ton of awards, especially for the masterful performances of Daniel Day Lewis, Sally Field, and Tommy Lee Jones. For me, I was most impressed with the staging, the pre-electric gloom of the interiors, and the overall fidelity to detail in costuming and decor. The movie felt authentic.

Throughout the first 2/3 of the movie I was enthralled and believed that Spielberg had finally reined in the populist pandering that infects pretty much everything he touches. But the final scenes leading to the passing of the 13th amendment featuring buffoonish characters cajoling votes out of fencing sitting congressmen, the comically raucous debate in the House of Representatives, and the overtly telegraphed dramatization of the final vote left me deflated, though I still clung to the earlier positive glow. Since seeing the movie, I found out why these last scenes, the voting segment in particular, rang false. The depiction of this well-documented event was manipulated for dramatic purposes.

From Maureen Dowd in the Times:

And then there’s the kerfuffle over “Lincoln,” which had three historical advisers but still managed to make some historical bloopers. Joe Courtney, a Democratic congressman from Connecticut, recently wrote to Steven Spielberg to complain that “Lincoln” falsely showed two of Connecticut’s House members voting “Nay” against the 13th Amendment for the abolition of slavery.

“They were trying to be meticulously accurate even down to recording the ticking of Abraham Lincoln’s actual pocket watch,” Courtney told me. “So why get a climactic scene so off base?”

The screenwriter Tony Kushner defends the changes this way:

…it is completely acceptable to “manipulate a small detail in the service of a greater historical truth. History doesn’t always organize itself according to the rules of drama. It’s ridiculous. It’s like saying that Lincoln didn’t have green socks, he had blue socks.”

The problem is, this easy willingness to distort the facts betrays the thinking that went into the whole enterprise. Small details matter. Maybe not the socks, but the actual votes of congressmen, yes. As Mies van der Rohe, the creator of sublime modernist buildings once noted, “The devil is in the details.”

The other two movies in the discussion are Zero Dark Thirty, which tells the story of the raid on Osama Bin Laden’s compound, and Argo, the story of the escape of six American diplomats from revolutionary Iran in 1980. Both movies make the pretense of portraying actual events exactly as shown on the screen. In Zero Dark Thirty CIA agents use torture to obtain critical information–it did not happen–and the diplomats in Argo make a wild skin-of-the-teeth getaway in the Tehran airport–it did not happen.

The argument in all three cases is that artistic license allows for embellishment, dramatic manipulation, and even making things out of whole cloth. As Manholo Dargis and A. O. Scott write at the conclusion of their tortured article in the Times:

Given some of the stories that politicians themselves have peddled to the public, including the existence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, such concern is understandable. It can often seem as if everyone is making stuff up all the time and in such a climate of suspicion and well-earned skepticism — punctuated by “gotcha” moments of scandal and embarrassment — movies are hardly immune.

But invention remains one of the prerogatives of art and it is, after all, the job of writers, directors and actors to invent counterfeit realities. It is unfair to blame filmmakers if we sometimes confuse the real world with its representations. The truth is that we love movies partly because of their lies, beautiful and not. It’s journalists and politicians who owe us the truth.

Sorry guys, but this is not how everyone operates as an artist. What I do as a photographer, for instance, is not a “counterfeit reality.” It may not be reality itself–certainly not–but it is a reflection of reality, one that I take great care in preserving even as I make the critical decisions about where to stand, what to show or not, or how to sequence images. The fact that politicians are routinely lying about things like WMD, that teachers are claiming that creationism shares the same legitimacy as science, that right wingers pretend that President Obama is a Kenyan, that paranoid leftists blame the World Trade Center destruction on a U.S. government conspiracy, is exactly the point. We are a society playing fast and loose with the facts, and artists are as culpable as anyone else.

There are lines that need to be drawn and redrawn, despite constantly shifting ground. It is one thing to interpret historic events, to fill in the blanks between things that are known, to speculate on what might have happened when the facts are sketchy. It is another to willfully ignore the tangible, the provable, to fail to see the infrastructure of history and respect the body of knowledge that supports society. It was said that the Bush administration “fixed the facts around the policy” with regard to the war in Iraq. Artists do the same all the time without, of course, the life or death ramifications. Spielberg and Kushner had a climactic scene to their movie, the vote on the 13th amendment. They determined what dramatic sequence of events worked best “artistically,” and then fixed the facts around the policy.

I know it’s just movies, but I take this stuff seriously.

Time and Space on the Lower East Side will be exhibited at Dillon Gallery from March 7 to April 9. Dillon is on West 25th Street in the gallery district of Chelsea on the same block as Pace Gallery and the Tesla electric car showroom. Like most of the galleries in Chelsea, it was originally in Soho. Although they are known mostly for paintings–and even an artist who works in scents–the owner Valerie Dillon was open to considering photography, and decided a few months ago to take me on as one of her artists.

The gallery is quite large, easily accessible on the ground floor, and will provide plenty of wall space to present my Lower East Side pictures at a scale that is impressive, but appropriate for view camera images. There will be 26 images all together, and twelve will be printed 4×5 feet, enough images to present an overview of the whole project with the focus slightly skewed toward the 1980 images made with Edward Fausty, which may have the most sales potential.

The opening is March 7 from 6 to 8pm, and everyone is invited.

Broadway and East 9th Street — © Brian Rose

Ridge Street — © Brian Rose

A few random pictures and random thoughts. As my Lower East Side show approaches I wonder how (or if) the work will be put in context with the photography being made back in the late 70s, and the way in which I connect the work to the present. One of the important points I have tried to make in the book is that the past and present are intertwined, and not neatly separated into before and after as is the usual practice. That said, the photographs I did with Edward Fausty were made as color photography was just beginning to enter the mainstream of art photography. The way we used color and the view camera to describe the streets and architecture of the LES at a particular moment in history had not been done before–at least to my knowledge–and has only been done rarely since. I think of recent work by Robert Polidori in Havana or Andrew Moore in Detroit as examples of the latter. But in 1979 I was thinking about the steady gaze of Atget and Evans with the view camera, and the kinetic energy of Frank and Friedlander with the 35mm.

There’s a book coming out soon called Color Rush by Katherine A. Bussard and Lisa Hostetler that tells the story of color photography from its inception to the early ’80s. The website blurb says: The book begins with the 1907 unveiling of autochrome, the first commercially available color process, and continues up through the 1981 landmark survey show and book The New Color Photography, which hailed the widespread acceptance of color photography in contemporary art.

Alas, my LES work will not be included. It was shown in 1981 in a large exhibition, reviewed in the Times, but then went underground not to be seen again until now with Time and Space on the Lower East Side. I’m not going to go into the reasons why that happened–for the moment–but what I feel good about is that the re-emergence of this work is not primarily a nostalgia trip back to the ruins of the past. It is presented as a fresh portrayal of a place, one that challenges easy assumptions about how to look at the past and how to look at photographs of different eras juxtaposed as they are in Time and Space.

Joerg Colberg on his blog Conscientious recently reviewed the reissue of the book American Prospects by Joel Sternfeld. He states: As a photographer, Sternfeld has certainly had enormous influence on a whole generation of American photographers. For example, it is not hard to see Alec Soth’s Sleeping By The Mississippi follow some of the traces laid out in Sternfeld’s travels and book. The American large-format photography craze might be on the way out now, though – just like its German (Düsseldorf) counterpart it simply appears to have run its course.

I guess there was a craze at some point, but I hate to see things discussed in this off-hand way, that a certain popular style has just run its course, and we can now move on. I’m picking on Joerg here, a thoughtful writer about photography who was writing a positive review of Sternfeld’s book, but for me, my work has little to do with any kind of craze or particular attachment to the influence of contemporary photographers. It has been a long hard slog stretching over decades.

Critics, curators, and the art market are, of course, fond of defining movements and putting things into convenient boxes. A photographer does something innovative, which is then shown in the galleries, the critics jump, and then the art students follow en masse. This is an obvious scenario, but it goes on and on. At any rate, I am proud to be one of the early adopters of color photography dedicated to a descriptive exploration of the landscape. And as I continue to extend my long term projects and begin new ones, I will not accept the notion that looking at the visually tangible world with a critical eye has lost its relevance to contemporary art and culture.

If you stand right fronting and face to face to a fact, you will see the sun glimmer on both its surfaces, as if it were a cimeter, and feel its sweet edge dividing you through the heart and marrow, and so you will happily conclude your mortal career. Be it life or death, we crave only reality. If we are really dying, let us hear the rattle in our throats and feel cold in the extremities; if we are alive, let us go about our business.

–Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Comparing two tests before making a 50×62 inch print — © Brian Rose

I have completed printing for my upcoming show at Dillon Gallery in New York City. The opening is March 7, and I’ll be posting a formal invitation soon. Yesterday I spent about eight hours in the lab shepherding my digital files through the process of printing them on paper. Although many photographers now use inkjet printers, I still find the look and feel of c-prints preferable for my work. The beauty of older analog color prints was the naturalistic color and slight softness in rendering light and detail. So much of what you see these days in galleries and museums is over saturated, over contrasty, and over sharpened–brittle. Photoshop is the most wondrous of programs, but it is also a Pandora’s box, and no matter what kind of print you make, digital c or inkjet, the temptation is always there to do too much.

Most of my project work–fine art photography–I continue to use 4×5 film. There may come a day when I switch over to digital, but we’re not quite there yet. In this case, with the Lower East Side work, it is especially nice to place images next to each other taken 30 years apart all made on essentially the same material. The big difference now is that I scan everything, both old and new, and do all the color correcting in Photoshop. Analog projection printing was generally limited to making global corrections, like adding or subtracting yellow from the mix. One worked step by step gradually finding a color balance that felt natural, had a sense of depth, that felt clean, unmasked. Many negatives, however, presented challenges and I was never wholly satisfied with the results. Photoshop provides tremendous control of every aspect of the image, and I’m not talking about the kind of manipulation that everyone is familiar with. I’m talking about the ability to make subtle, carefully modulated changes that enhance the overall quality of the image. Once you’ve become proficient in Photoshop, there’s little nostalgia for the old analog method.

One of the recent images from Times and Space on the Lower East Side coming off the machine — © Brian Rose

In the case of the images I did with Ed Fausty in 1980, it isn’t possible to make decent analog prints, even if I wanted to. The different layers in the film emulsion have faded or shifted, and the color balance has been has been permanently thrown off. I tried making analog prints from the old negatives some years ago, but gave up after a few hours of futility. Digital has essentially saved these images. It can be a lot of work–hours, even days–coaxing the color out of the old negatives. The results, however, are often amazing–prints that are far better than the original prints.

Nowadays you are not really making the image in the darkroom as before. Most of the work is done in Photoshop, and lab is the final step. Typically, I bring my digital files on a flash drive, copy them onto the server at the lab, look at the images on their setup to see if looks much different than my studio computer. Usually, the difference is minimal, and one or two sets of small test prints are all that is needed before going to the full size prints. In this case, I am making 50×62 and 20×25 inch prints.

Orchard Street in 1980 coming off the machine at Beth Schiffer Labs in lower Manhattan — © Brian Rose

There will be 25 prints in the show at Dillon, about half of them in the size seen above. Not having printed this large before, it was pretty awesome seeing the images roll off of machine. There is a tendency these days to print too large–mostly for market reasons rather than aesthetic–but these images were made in 4×5 for the monumentality that the format brought to the subject. It was one of my goals when undertaking the Lower East Side Project, to describe, amplify, and preserve for all time the streets and architecture of the place. Printing this size achieves that original goal. Ed and I made several large prints–30×40 inches–in 1981 when we exhibited the work at the Henry Street Settlement. It was incredibly impressive then to see color prints of that size. It’s more routine now. But I think these images will impress nevertheless.

Joe Henderson, Jeff Hardy, Jack Hardy, and Howie Wyeth, late ’70s — © Brian Rose

I’ve written before about Jack Hardy, my songwriter friend, who died almost two years ago. I recently attended a memorial service for his father, Gordon Hardy.

An earlier post here. And jackhardy.com here.

Jack cultivated the role of the self-taught itinerant folk singer living hand-to-mouth even as he proudly told the story of the Studebaker family—his mother’s side–in the song Wheelbarrow Johnny. What is less known is the importance of his father, former dean of students at Juilliard, and president of the Aspen Music Festival. Jack grew up in a household steeped in classical music. One photograph displayed at the reception showed Gordon Hardy and the composer Aaron Copland. That’s the world Jack came from.

Shortly after Jack passed away I wrote a fairly long chronicle of the early days of the songwriters exchange, the arrival of Suzanne Vega on the scene, and the creation of the Fast Folk magazine. It was intended for the Jack Hardy tribute album organized by Mark Dann, which is still not widely available, and I doubt that many have read it. The death of Jack’s father spurred me to reread the piece, and I’ve decided to post it here on my blog. Some of the story may be familiar to those who knew Jack well, other parts new, even surprising.

Please forgive the many names left out, and other oversights. It’s a personal recounting, not a comprehensive history.

Travelers Passing Through: Boulevardiers and Fast Folk