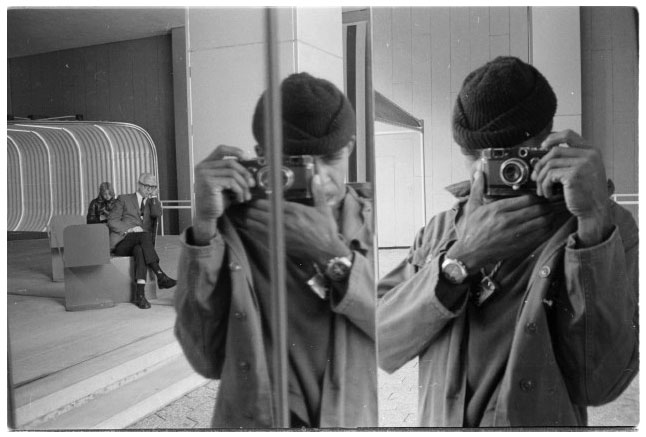

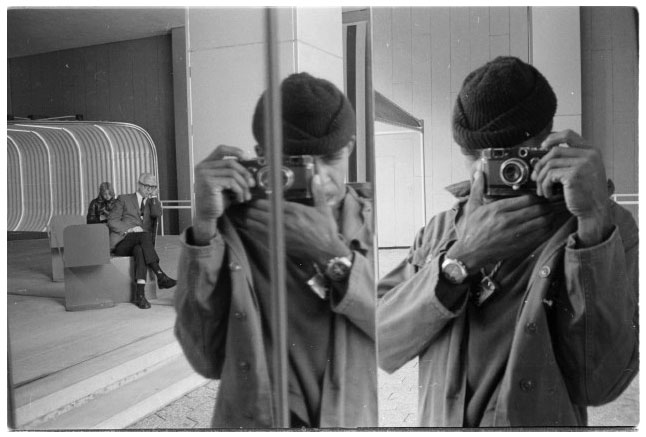

Alex Harsley, self-portrait

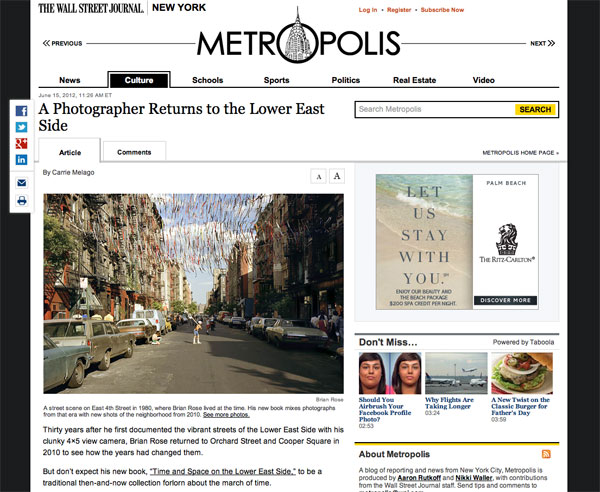

I’ve written about Alex Harsley several times in this blog, a woefully overlooked photographer and icon of East 4th Street, where he maintains a gallery on the block pictured on the cover of Time and Space on the Lower East Side. Alex currently has a show up at the June Kelly gallery on Mercer Street, and a few days ago Holland Cotter gave it a review in the New York Times.

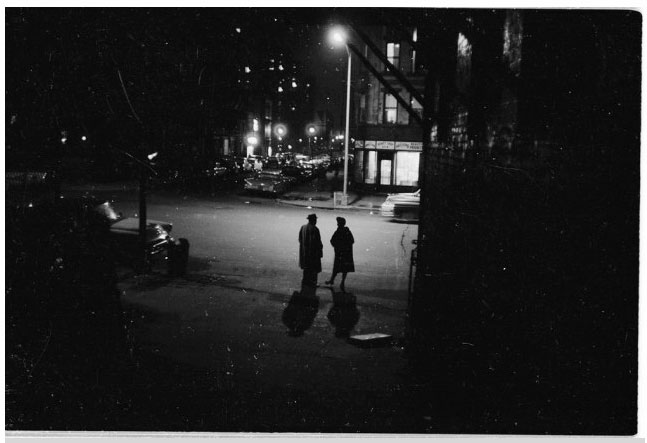

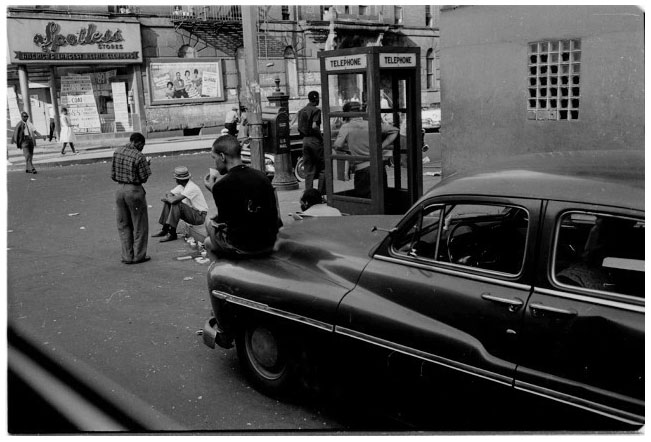

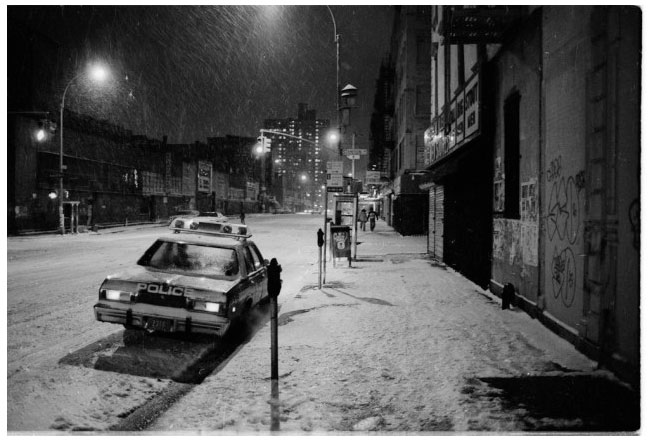

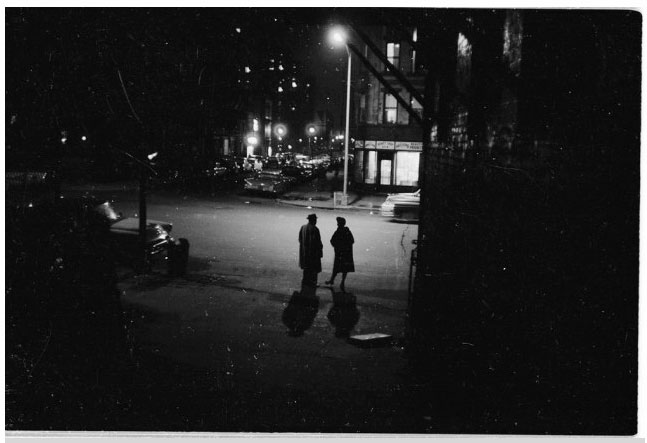

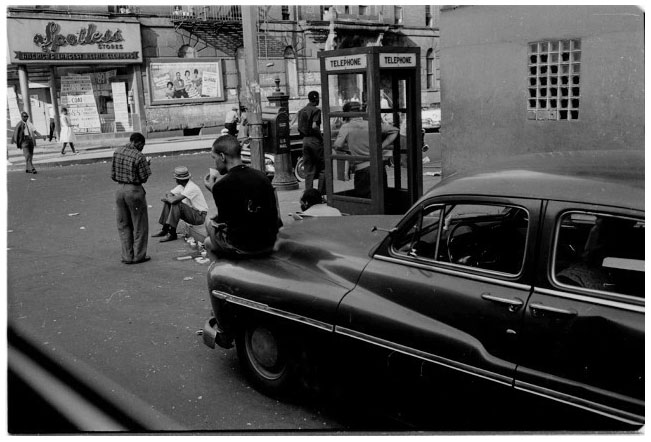

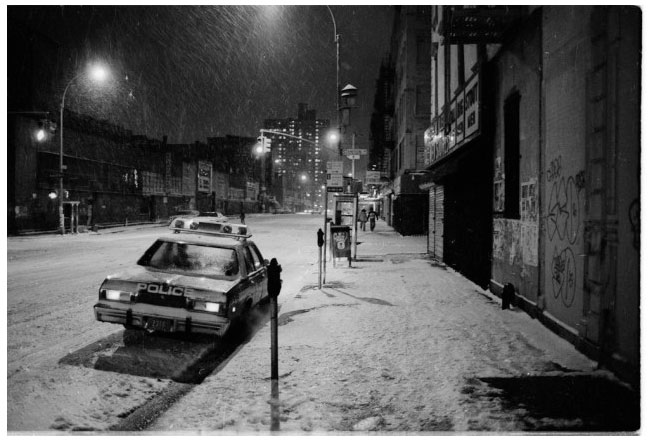

The exhibition at June Kelly surveys a half-century of Mr. Harsley’s own estimable art. Born in South Carolina in 1938 and a New York resident since childhood, he has made the city a primary subject of his classical brand of “street photography,” from shots of life in Harlem in the 1950s to velvety black-and-white images of downtown, late at night and silent, under snow in the 1990s.

The gallery exhibition presents Harsley’s work as a 50 year retrospective, and while it does cover that period of time, it does not in any way offer a definitive overview of his life’s work. There are a number of reasons for why that is a difficult task to accomplish, which I will get to in a moment. Unfortunately, the show feels thin. It seems a grab bag of notable images rather than a carefully selected survey suggesting the depth of Harsley’s long career. Moreover, the print quality is all over the place, and the presentation is sloppy, the cheap metal frames not meeting at the corners.

For many years, the best way to see Harsley’s work is to go to his gallery on East 4th Street where he hangs his work salon-style all over the walls, the unframed prints clothes pinned on string, and Alex himself present to answer questions, comment, or ramble on about the state of the world. If you stay long enough, he’ll coax you into the back room of his tiny tenement gallery where he works on his videos. I haven’t figured out what I think of these, yet, but this is what Alex has focused on over the past decade.

The Barnes Collection was recently transplanted from its original mansion setting on the edge of Philadelphia to a modern museum building on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the rooms of Barnes’s crazily inspired world recreated precisely in the new more accessible location. As I walked through the Harsley exhibit at the June Kelly gallery with each picture presented in a line with generous space between, I missed the unruly interior of Alex’s salon back on 4th Street, and almost wished they had done a Barnes here, and moved the whole thing including Alex into the gallery.

That said, however, I think it’s high time that Alex Harsley’s photography be presented in a way that allows individual images to be appreciated, for the various threads of his work to be explored, and for him to assume his rightful place as an important contemporary photographer, and historically, one of the most important African American photographers. Holland Cotter in his New York Times review calls for “an institutional career survey” and writes further, “And surely the time has come to put a history of that career between the covers of a book.”

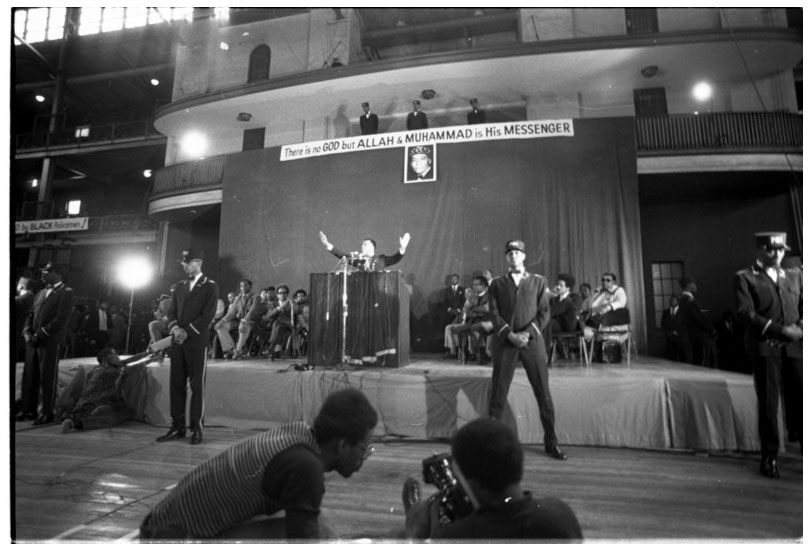

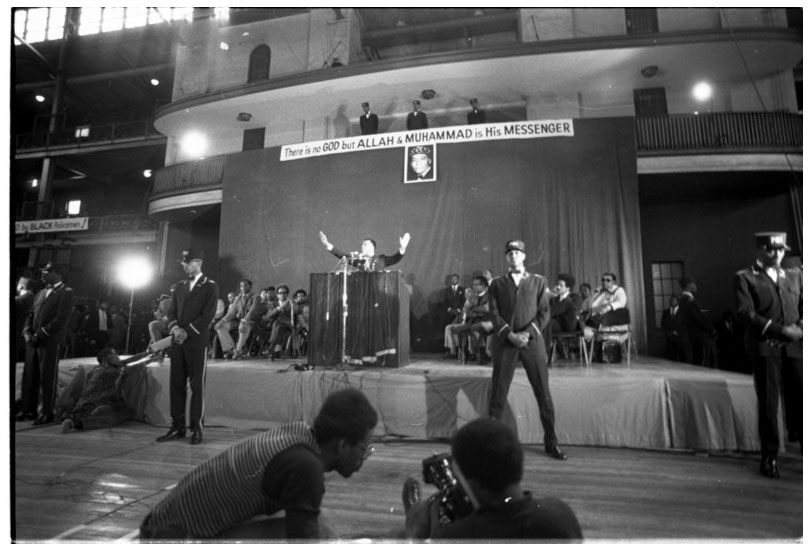

Malcolm X

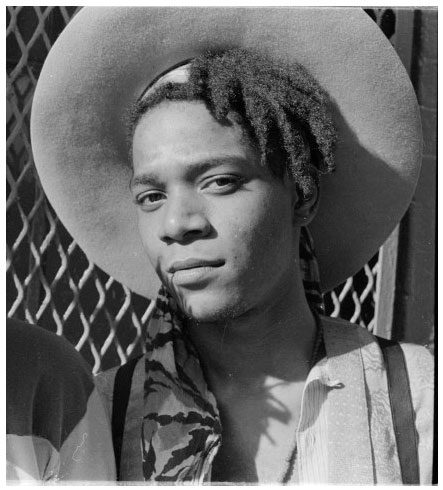

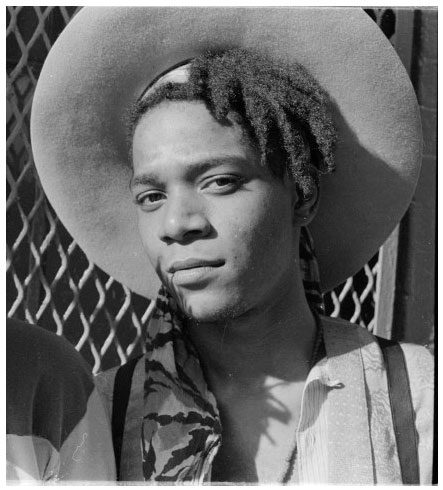

Jean-Michel Basquiat

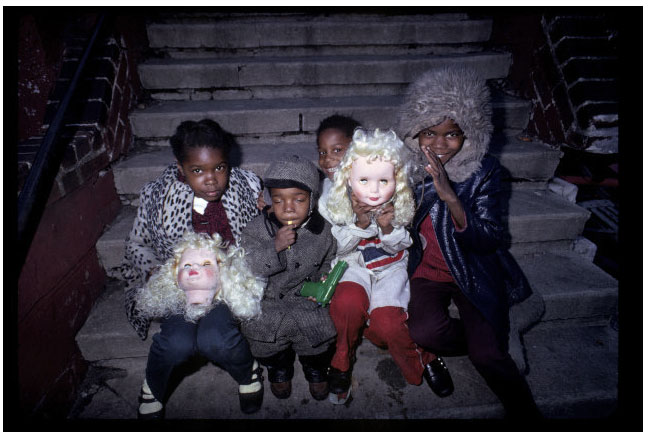

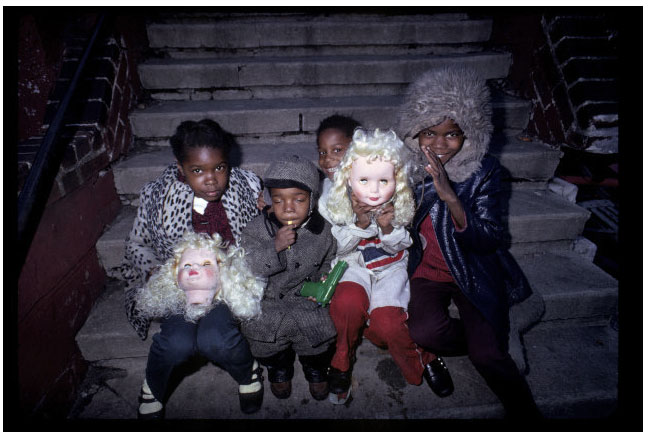

A rare color image

Part of the problem, surely, is that Harsley has made himself an outsider–sometimes willfully. But to a great extent it’s simply because he has never moved among the right circles of people, pushed the right buttons, never sought out the recognition that most others naturally chase after. His archive is, from what I can tell, a mess. There are undoubtedly thousands of negatives, and perhaps, dozens of great images never seen, never printed. I have no idea whether Alex would trust the work of sifting through his life’s work to a skilled researcher or curator, but I believe it needs to be done.

I cringed the other day seeing celebrity pictures of “A Life in Pictures, the Gordon Parks Centennial Gala” at the Museum of Modern Art. Parks, who died in 2006, is hailed as one of the great Black photographers of the 20th century. He worked for Life magazine, was a fashion photographer, documented the civil right movement, and made notable portraits of famous individuals. His work expresses the concept of photography as an instrument of social justice and projects images of human dignity and nobility. For me, however, Park’s images are often clichés of the type, as much about a certain accepted style as substance. He undoubtedly has his place in the history of magazine photography, but…

From Vogue magazine:

On the ground floor of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, at a gala celebrating the 100th anniversary of legendary African-American photographer, writer, and director Gordon Parks’s birthday, and honoring Alicia Keys, Annie Leibovitz, and HBO copresident, Richard Plepler, well-heeled guests mingled over cocktails and a series of silent-auction photographs while publicists yelled out the names of the A-list guests as they approached the red carpet. “Josh Groban‘s coming,” a girl hollered over the din, causing more than a few heads to turn toward the flurry of flashbulbs. “Josh Groban!” Despite the excitement, luminaries were not in short supply at the dinner, which boasted tables packed with names like Sarah Jessica Parker, cochair Karl Lagerfeld, Thelma Golden, and John Legend. The annual event, which raised $750,000 for The Gordon Parks Foundation, was kicked off by the evening’s host, Anderson Cooper, who recounted the life of Parks, who was born—one of fifteen children—in Kansas and rose in New York City, through hard work, to the top of his chosen field, becoming known for his photography for Life, Vogue, and many others, for directing films like Shaft, and for his humanitarian efforts. By the looks of the room, filled to capacity with his admirers and his photographs, it is a legacy well worth celebrating.

The photographic world of Alex Harsley intersects with that of Gordon Parks, but it a world portrayed in a drastically different way. He, too, photographed images that deal with racism, poverty, and even celebrity. But his images rarely strike that “family of man” chord that Parks played so well. In the image above, one of many Harsley nocturnal scenes, we are in the city, possibly the Lower East Side. The street is deserted, bedecked in steadily falling snow. A police car idles, lights on. A couple of individuals approach in the distance. There is no conventional meaning here. It is a moment of hushed solitude, of uneasy anticipation, composed without artifice, presented without statement. Only clarity of vision.

.