Berry Street, Williamsburg — © Brian Rose

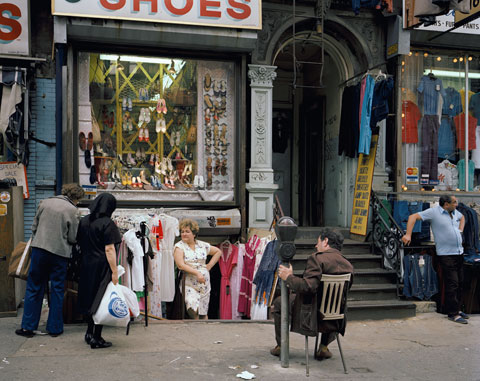

A very nice post about one of my Lower East Side photographs from 1980.

Berry Street, Williamsburg — © Brian Rose

A very nice post about one of my Lower East Side photographs from 1980.

Somewhere in Wyoming, 1981 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

First some disappointing news. My application for a grant from the Graham Foundation to photograph the New Religious Landscape, a project focused on Megachurches and their surrounding areas was unsuccessful. At this point, it is just about impossible for me to take on ambitious projects like this without external funding.

I’ve spent the last two days writing an article for a special edition of the Fast Folk magazine dedicated to Jack Hardy, the late songwriter. Scroll down for earlier posts on Hardy. It is basically the story of my relationship with Jack from 1977 to 1984 during which time we hung out in Greenwich Village folk clubs,, traveled across country together and established the Fast Folk, a monthly LP/magazine of the latest songs from our weekly songwriters meetings. I may post the article here later, but I don’t want to preempt the Fast Folk, which will be available online–probably through the Smithsonian Folkways record label. Stay tuned for that.

The photograph above was taken while driving with Hardy through Wyoming in 1981. There are many other pictures from that trip, and none have ever been printed. A slight light leak in my view camera caused streaking on about half of the images making them near impossible to print–the old way in the darkroom. The defect is easily remedied with Photoshop. So, stay tuned for a series of images taken all over the United States in the early ’80s.

Chrystie Street — © Brian Rose

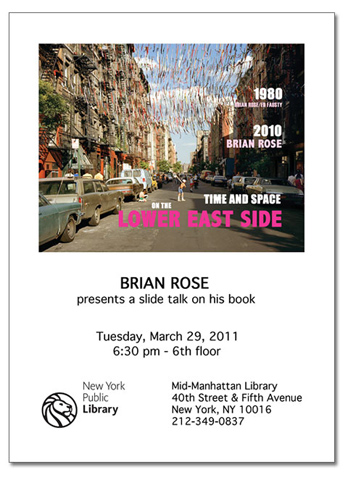

My slide talk went well last night at the Mid-Manhattan library. I heard there were 58 people in the audience. Ed Fausty who did the 1980 Lower East Side photographs with me was there and participated in the Q&A. I sold a few books, and talked with lots of people afterward.

I stepped through Time and Space on the Lower East Side reading most of the text pieces and adding a few additional comments here and there. Since I was showing the images one at a time, some of the connections between images–on facing pages in the book–were not so easily made. I don’t mean actual before/after pairs, which are obvious enough, but other less direct relationships. But it was my choice to fill the screen with large single images rather than show pairs at a smaller size.

Here is a review of the slide talk.

***

Today I am recording one of Jack Hardy’s songs for a special project dedicated to the late songwriter. Jack died a couple of weeks ago–a great shock to all of us in the folk songwriting community in New York and elsewhere. Jack and I founded the Fast Folk back in 1981 with the intention of getting new songs on the street quickly while still fresh. I will write more about the Fast Folk in the future. Tomorrow there will be a memorial event:

Jack Hardy Memorial Gathering in New York City: There will be an evening of song in memory of Jack, hosted by David Massengill, on March 31st, 2011. It will be at the Christopher Street Coffee House, in St. John’s Lutheran Church, at 81 Christopher Street. There is more information on the Christopher Street Coffee House web site

A number of YouTube videos of Jack Hardy performances have been added recently including this one from the 50th anniversary of the former Village folk club Folk City. It was the last time I saw Jack perform on stage. I was doing still photographs for the event and that’s the back of my head interfering with some of the video–sorry. This is Jack at his best surrounded by terrific musicians including Kirk Siee on bass, Mark Dann on guitar, and Lisa Gutkin on violin. Jack’s daughters Morgan and Miranda sing harmonies, and midway through, Terre Roche joins them.

And here’s a video of Suzanne Vega visiting the songwriters’ exchange at Jack Hardy’s apartment on Houston Street. I wasn’t there that day, but I see several familiar faces–Tim Robinson, Frank Tedesso, and Erik Frandsen–three of the best songwriters around.

Last weekend I went to AIPAD, the giant photography dealer’s fair at the Armory on Park Avenue. I don’t have any particular opinion about what I saw–a lot of photographs–no trends spotted. Not enough time or energy to think critically about such a dizzying display of dreck to pearls. Primary observation: more galleries present and a number from outside New York. Business seems to be picking up. So far, it’s not helping me.

Afterward, I dashed uptown to the Guggenheim to meet my sister who was visiting from San Francisco. We wanted to see a video installation by Omer Fast who in 2005 made a piece dealing with Williamsburg, Virginia, the restored colonial capitol, and where we grew up.

From the 2008 Whitney Biennial:

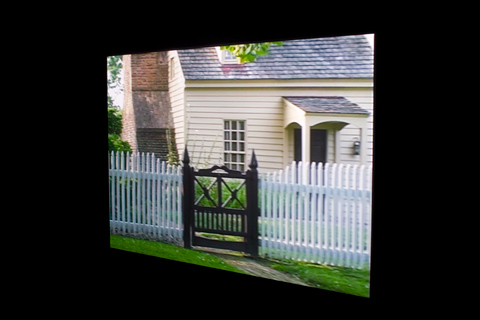

In Godville (2005), a 51-minute, two-channel color video, historical reenactors at the Colonial Williamsburg living-history museum in Virginia describe their eighteenth-century characters’ lives and their personal lives in ways that seem interchangeable. Fast splices the reenacted and real biographies together, often word-by-word, into a rambling narrative that is as aurally fluent as it is temporally dissonant. The work tells the story of a town in America whose residents are unmoored, floating somewhere between the past and the present, between revolution and reenactment, between fiction and life.

Godville by Omer Fast — seen at the Guggenheim Museum — © Brian Rose

Both my sister and I played roles in the open air museum of Colonial Williamsburg. I was part of the fife and drum corps, a professional musical group that performed regularly for visitors as well as for presidents and dignitaries. My sister was a costumed ticket taker, and later a costumed sweeper hostess at the nearby Busch Gardens “old Europe” theme park. A sweeper hostess, as I understand it, picked up trash and chatted with tourists.

I found the film fascinating, though unsure about its ultimate message. I liked the idea of intercutting between real and fictional, and in the process blurring the lines. I have made photographs of the architecture of Colonial Williamsburg, and was particularly interested in the juxtaposition of views of the historic structures and contemporary suburban neighborhoods. Confusing, however, was that many of the contemporary architectural and landscape images shown were not made in Williamsburg, but in unidentified generic locations. Some of the images included mountains and scenes from the west, which I presume was intended to allude to larger American mythological themes.

Godville by Omer Fast — seen at the Guggenheim Museum — © Brian Rose

Three costumed reenactors spoke either in character or from their real life experiences. Some of the time they were shown speaking uninterrupted, other times their words were chopped up and reconnected. The depiction of these people–and their words–is extremely manipulative, but I can’t say that they were shown unsympathetically or portrayed unfavorably. It is, however, a highly problematic approach. Knowing what I know about art and media, I would be very wary of participating in such an enterprise.

Godville by Omer Fast — seen at the Guggenheim Museum — © Brian Rose

In so many ways Colonial Williamsburg is an easy mark. It is easy to see it as kitsch and a distortion of American history. Too easy. There is lots of room for critical analysis, but unfortunately most of it to date has been facile. Omer Fast’s Godville, despite my reservations, is worth seeing and thinking about. Not that many people visiting the Guggenheim are doing that. In the hour that I spent watching the video in the museum on a busy Sunday afternoon, not one person gave it more than a minute’s attention.

Colonial Williamsburg outbuildings (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Which brings me to my own work dealing with Williamsburg. A number of years ago I photographed the outbuildings and surrounding gardens behind the main buildings. The pictures deal with the structures as architectural vocabulary filtered through modern interpretation and context. On the one hand they reveal the complex dichotomy of old and new, and on the other hand they are what they are–formally composed, often beautiful, collections of little buildings, fences, and trees.

Since it appears I will be continuing to go down to Williamsburg in the future–my father still lives there, and my mother may return there soon, I am thinking I should revisit the project. The idea I have is to photograph some of the new urbanist communities that have been developed outside of the restored area–places that recycle the architectural and urban planning vocabulary of the past–and juxtapose those pictures with the ones I have taken of the outbuildings and dependencies of Colonial Williamsburg.

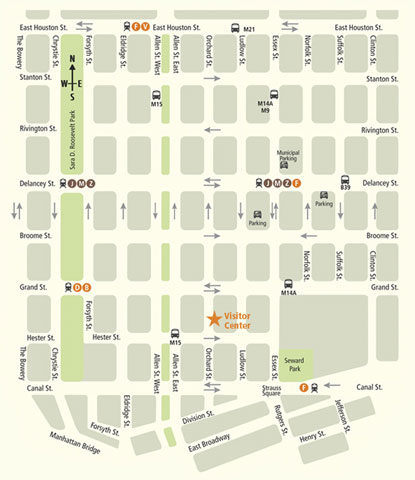

The reception at the Lower East Side Visitor Center went well. A mixture of invited guests and people passing through as part of Third Thursdays, a once a month evening when the galleries in the neighborhood stay open later. The prints look great on the wall, and they will be up through April 21. Drop in at 54 Orchard Street, ground floor.

Next up is my slide talk at the Mid-Manhattan library on March 29. I will be presenting Time and Space on the Lower East Side, and I am hoping that Ed Fausty, who I collaborated with on the 1980 photographs, will be present. Ed is working on an exhibition and catalog for a beautiful series of photographs on the landscape and night sky. Unlike anything anybody else has done. I’ll write about it once it’s up.

The following photos were snapped yesterday on my way to and from my LES exhibit.

Orchard and Grand Streets — © Brian Rose

Orchard Street, 1980 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose/Ed Fausty

My exhibition at the Lower East Side Visitor Center begins this evening–reception from 6 to 8pm. Art galleries throughout the Lower East Side will be open until 9pm. Maps and guides are available at the Visitor Center. Please feel free to stop by and say hello. The show will have 14 images primarily of the area below the East Village, an equal number between 1980 and recent photographs. The show will run through Thursday April 21.

54 Orchard St. (between Hester and Grand)

New York, NY 10002

212-226-9010

Orchard Street, 1980 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose/Ed Fausty

My exhibition at the Lower East Side Visitor Center begins tomorrow evening–reception from 6 to 8pm. Art galleries throughout the Lower East Side will be open until 9pm. Maps and guides are available at the Visitor Center. Please feel free to stop by and say hello. The show will have 14 images primarily of the area below the East Village, an equal number between 1980 and recent photographs. The show will run through Thursday April 21.

54 Orchard St. (between Hester and Grand)

New York, NY 10002

212-226-9010

Jack Hardy in his apartment on Houston Street (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Jack Hardy, the extraordinary song craftsman, and one of my most cherished friends died last night of cancer. New York Times obituary here.

From The Boulevardiers by Suzanne Vega:

(I am the tall lover of the city, Jack the quick and fair.)

He loves the city with the bricks and broken bottles

and the pretty little flowers as they grow against the wall.

He is dark, he is tall, he is the tallest one of all of us.

You are bright and quick and fair

and seems that you have lost some hair

but this is all right.

This is OK. We do not mind.

We write and fight and sing

and this is fine.

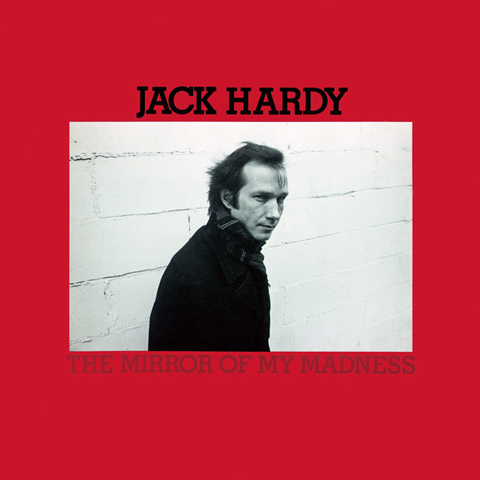

This is the cover of one of Jack’s earliest albums. I did the photograph. It was originally a blank LP sleeve, and we called it the White Album. At some point a record company picked it up and a proper cover was made. I don’t remember the location of the photograph, but it was undoubtedly somewhere in Greenwich Village, or very possibly near my apartment in the East Village.

When I met Jack in 1977 he was a charismatic figure full of a sense of personal destiny. The picture above expresses some of that ambitious confidence–and an image carefully cultivated. Later, the trajectory of his career leveled off, but his songwriting skills did not. If anything, they grew and deepened over the years.

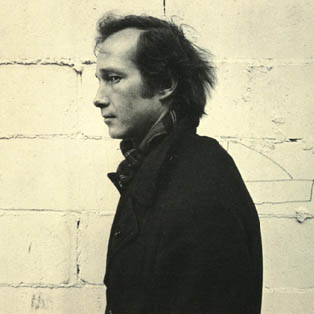

Jack Hardy — © Brian Rose

This photo found on the internet is from the same session as the one above. I do not seem to have the negatives, although I haven’t finished looking. I may have some prints. I am guessing that I gave the negatives to Jack shortly after they were made, and they may be in his archive. Nothing was digital in those days, of course.

UPDATE:

Arrived somewhat late to an impromptu memorial concert at Banjo Jim’s, a small club in the East Village. I sang The Skyline, my song about 9/11, which was partly a response to Jack Hardy losing his brother in one of the Twin Towers. I did it a capella, less than perfectly, but I give myself some credit for bravery. Several people did wonderful versions of Jack’s songs, and we ended with Go Tell the Savior led by David Massengill with one of the verses sung beautifully by Jim Allen. I hear that a bigger, more formal memorial is being planned.

MORE PHOTOS:

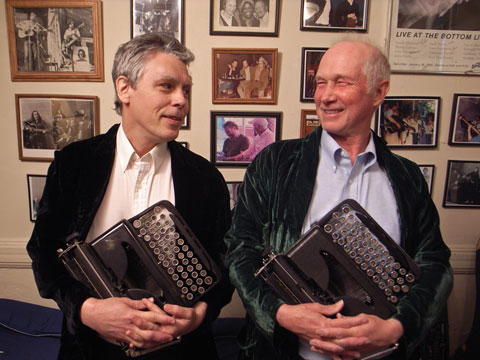

The Folk Brothers, David Massengill and Jack Hardy, 2010 — © Brian Rose

Folk City 50th anniversary, Mark Dann and Jack Hardy, 2010 — © Brian Rose

Jack Hardy and David Massengill, Houston Street apartment — © Brian Rose

Couch in Trees by Andrew Moore

I went to a slide talk by Andrew Moore at the Mid-Manhattan library last night. I’ll be doing a talk there myself on March 29–see my homepage for information. Moore is around my age, also an early practitioner of color, and normally uses a view camera. Moore’s latest work deals with Detroit, principally what has happened to this once great industrial powerhouse, now a symbol of American decline.

Many of Moore’s photographs describe the ruins of Detroit. Much has been written recently about “ruin porn” and photographic exploitation, and Moore’s work is frequently pointed to–either positively or negatively. I am not prepared to comment at length on the subject, at least for the moment, but I will say that Moore came across last night as open and sympathetic. There was some push back from several people who have roots in Detroit and who feel that Moore’s work does not treat the place altogether fairly. But in general I felt it was a useful and respectful conversation all around.

Here is an article about the subject.

I will be addressing some of the same concerns when I do my presentation in two weeks. I expect that some people will appreciate my evenhanded approach to photographing the Lower East Side, while others may feel that it doesn’t engage the politics of gentrification directly enough. I, too, have photographed ruins–as well as new construction. Sometimes it is hard to tell the two apart, which is one of the points I want to make.

23rd Street subway station — © Brian Rose

Sucker Punch.

Lower Manhattan by Corinne Vionnet

Photographic plagiarism is an almost meaningless concept. I don’t mean the stealing of copyrighted images, which is generally a well-defined legal matter, but the idea that particular images of places and things are proprietary, that repeating the same view, or imitating another photographer’s compositional approach, constitutes an infringement of someone’s unique vision. It is possible to point disapprovingly at photographers who deliberately copy the work of others. You can call them unoriginal, even unethical. But it is a slippery slope to go down because the reality is that the visual world is fair game.

Corinne Vionnet’s images of popular tourist sites around the world demonstrates this well. She combines hundreds of photos available from Flickr and other photo sharing services taken from similar perspectives creating ghostly mimetics–pictures of pictures–expressing collective visual iconography.

Vionnet:

The images made by tourists are picture imitations. They demonstrate the desire to produce a photograph of an image that already exists, one like those we have already seen. It is in fact a style of manipulating the viewer. Why do we always take the same picture, if not to interact with what already exists? The photograph proves our presence. And to be true, the picture will be perfectly consistent with the pictures in our collective memory.

The Brandenburg Gate by Corinne Vionnet

I use the two image above because they include icons that have figured prominently in my own work. Although I strive for images that go beyond visual cliches, I have never entirely avoided the obvious or the commonplace. The urban landscape we live in–even the natural landscape–is to a great extent prepackaged, designed, and pre-consumed. I consciously work with and against these structural constants, both physical and those imprinted on our brains. The pictures below could easily work into Corinne Vionnet’s Brandenburg Gate compilation.

The Brandenburg Gate, 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

The Brandenburg Gate, 1989 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

The Brandenburg Gate (4×5 film) –© Brian Rose

All three of my Brandenburg Gate pictures are locked into the axial and symmetrical nature of the space and architecture, but they are all on some level meta-images, images about images, a step removed from representation of the icon itself.

As much as I feel that I own the subject of the Berlin Wall, and to a much lesser extent Berlin itself, there have been lots of other photographers who have covered the same terrain, sometimes coming up with startlingly similar images. I have known and admired John Gossage’s work since I was a student. His book The Pond has recently been re-released. I did not know, however, until a short time ago that he also photographed the Berlin Wall back in the 80s around the same time I was there. Here are two of our photographs taken from similar vantage points:

The Berlin Wall by John Gossage

The Berlin Wall (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

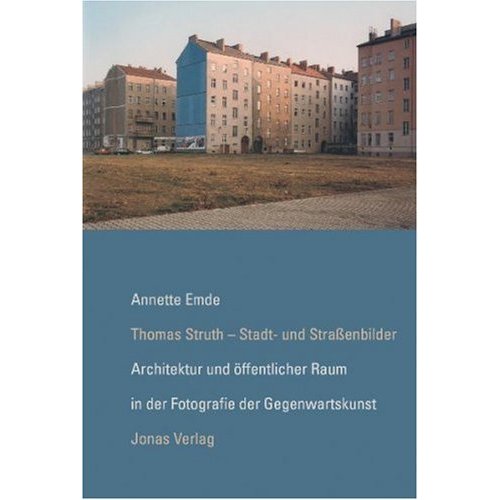

Another photographer I greatly admire is Thomas Struth, who has photographed streetscapes and architectural subjects all over the world including Berlin. Just after the Wall came down he and I, unknowingly, both photographed along Bernauerstrasse where a wide swath of former no man’s land sliced through rows of buildings in the neighborhood Prenzlauerberg. Here are two pictures:

Photograph by Thomas Struth

Bernauerstrasse (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

The world is awash in images. Legions of photographers, professional and amateur, have fanned out across the globe to document seemingly every scrap of land and every crumbling ruin no matter how banal. For me, it is occasionally deflating, thinking about this glut of imagery. But I have been doing this for a long time, doggedly following my nose where it leads, ignoring the trends and the crowds. Sometime, when I set up my view camera, people point their cameras over my shoulder, or even stand right in front of me and take a picture of what they think I am photographing.

What to make of all these similar images of the same subjects? For one thing, they are rarely identical. A millimeter this way or that can make all the difference. The transient quality of light and atmosphere. The passing stray cat, the discarded soda can, the random interplay of people moving through the scene. All these variables give the image its uniqueness. But what’s equally important, I think, is not the individual photograph, but the gradual accretion of images made over an extended period of time by a particular photographer.

I think it’s inevitable that photographer’s paths will cross and images occasionally overlap. You can’t copyright a view, and there are a lot of 1/125ths of a second to go around. Imitators will be seen for what they are. But don’t try to steal one of my images of the Brandenburg Gate. If you don’t want to pay for the rights, you can always go to Berlin, find where I stood, and get your own Brandenburg Gate.

Innovation is difficult to achieve in photography, particularly if one remains rooted in the descriptive side of the medium. There has never been a requirement, of course, that one stick to what is sometimes called “straight photography.” And from the get go, photographers have used the medium to create alternate realities–staged or transformed.

As is easy to tell from my work, I am partial to reality based photography, and I eschew what I see as passing technological fads that come during or after the fact of exposing an image on film or a digital sensor. Sure, we can get into semantic philosophical discussions about what reality is, or to paraphrase former president Bill Clinton, on the meaning of what is is. Be that as it may, I’d like to propose two trendy “innovations” for the nearest trash bin.

Selective focus tilt/shift photography. Olivio Barbieri did it first–or at least made a career of it first–and then there’s Miklos Gaal. And now there are legions of followers using either expensive tilt/shift lenses, like those used in architectural photography, or Photoshop to achieve similar results. The world looks toy-like, miniature. In all the pictures, all the time.

Photograph by Damon Winter from Lens Blog, the New York Times

Lens, the New York Times photo journalism blog brings to our attention a new effect. It’s the Hipstomatic app for use with cell phone cameras. It makes everything greenish, washed out in the middle, and contrasty. Damon Winter used it in making photographs of soldiers in Afghanistan, and he makes a very compelling case for the notion that he is telling stories with the camera, which allows for interpretive latitude. Others argue that it undermines the truth telling of photo journalism.

I have no problem with Winter’s perspective on story telling–I have grown skeptical of the highly selective “truthiness” of much photo journalism, and I applaud the efforts of photographers like Tim Hetherington to push the boundaries. In any case, my problem with effects like the Hipstomatic app is that they are so nakedly obvious. And as such I find it near impossible to see beyond the effects to what may be larger intended meanings.

JR, photographs on the Israeli West Bank barrier

The Times Magazine just did a multi-page article on JR, the “photograffeur,” who uses photography as street art. He photographs people in their communities and then blows up the images to huge size and pastes them to walls, buildings, even on the roofs of whole shanty towns–in the latter case visible only from the air. He gives faces and voices to people who are often unseen, unheard. This is photographic performance documented, integrated into the physical places where the images originate. This is brave stuff. Innovative. Not always legal. Using technology. Sometimes walking a thin line between empowerment and exploitation. But using the power of images and media in a new way. Without gimmicks.