E1st Street — © Brian Rose

Bicycles.

WTC book cover — © Brian Rose

WTC is now available for purchase. Call it a soft opening, I will be sending out books to key editors and individuals, and will endeavor to gradually get the word out. I will certainly do an announcement at my Lower East Side slide talk on March 29. Scroll down for information about that. I’ll be doing reminders as the date approaches.

The book is available in two sizes, 8×10 and 11×13. The large book is really beautiful. It is made with heavier paper, a bit glossier coating, hard cover only. It is $125. If you can afford it, get this one. The small book is available in either soft or hard cover at $45 or $57.

All my books are now available in the sidebar to the right or from my books page here.

Book cover with images by Bill Owens and Joe Deal

Final comments on Mark’s Rice’s Lens of the City, NEA Photography Survey of the 70s. I was a participant in one of these surveys in 1981. Scroll down for other posts.

Much of the book is spent exploring the art/documentary dichotomy, which was highly controversial during the years that the NEA funded survey project between 1976 and 1981. Many of the commissioned photographers operated in a traditional documentary manner–a sort of long form of photo journalism. But others, the ones we are most likely to know about today, were working under different precepts. These photographers, Robert Adams, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, among others, created images that were factual but neutral, allusive rather than didactic–and it was understood that photographic truth was by its nature contingent.

Many critics and viewers were unsatisfied with photography that did not “tell,” but rather suggested, or simply raised an eyebrow. It would seem that the result of all the projects funded by the NEA was an unfocused, discursive view of the American urban scene. Certainly, the project I was involved with–photographing the Lower Manhattan in 1981–was a curious mixed bag of photographic styles and approaches. Ed Fausty and I, working together and later alone, were the youngest of our group, and we were working in color with a view camera while the rest were shooting in black and white with small cameras. I don’t remember the other photographers’ work except for Larry Fink who photographed the hurly-burly atmosphere on the floor of the stock exchange.

The NEA projects may have been uneven in quality, but individual photographers often did exemplary, even groundbreaking, work. Several of the projects funded the work of single photographers with noteworthy results. Joel Meyerowitz’s St. Louis and the Arch and Lee Friedlander’s Factory Valleys were among the finest explorations of the urban landscape of their era. Friedlander’s project extended beyond place by incorporating images of people and the machines they operated. These are some of his strongest photographs–formally arresting, as always, but simultaneously expressive of the human condition.

In the end, the NEA survey grants were killed not so much by disagreement about what constituted art vs. documentary photography, but by the ascendancy of conservative politics. It did not matter that the survey grants were administered by local institutions and communities, nor did it matter that the grants were required to find matching funding from private sources. The survey grants ended with Ronald Reagan’s election, and in a few years, the individual artists’ grants would also be eliminated. We have had a neutered and ineffectual National Endowment for the Arts ever since.

Government funding of the arts will always be problematic, but when art is left primarily to the galleries whose interests tend toward protecting relatively small stables of brand names, the result is brutally Darwinian. Meanwhile, the schools keep churning out MFA grads, and a cottage industry built on webzines, blogs, contests and portfolio reviews picks up the slack, sometimes receiving funding from the NEA and private benefactors. But where is the support for individual artists? When I think of the burst of work done during the few years of the NEA survey grants–made for a minuscule fraction of the NEA’s budget of around $150 million in 1980–well, it’s obvious that our priorities are a tad skewed.

I don’t recall exactly how much money I got to do my photographs of Lower Manhattan. Maybe $2,500. At the time I was 27 years old, and it seemed like a fortune.

This is still a ways off, so this is an early alert. I’m planning to step through the book, reading short text pieces, and sharing observations and anecdotes. I will have a limited number of books for sale, and plan to use the occasion to announce my new WTC book. I will, of course, be available for questions afterwards, and look forward to meeting people. Hope to see you there!

This may be the first Blurb book presentation at the New York Public Library. A commentary of sorts on the state of photo book publishing.

Don’t worry, I’ll be posting reminders as the date approaches.

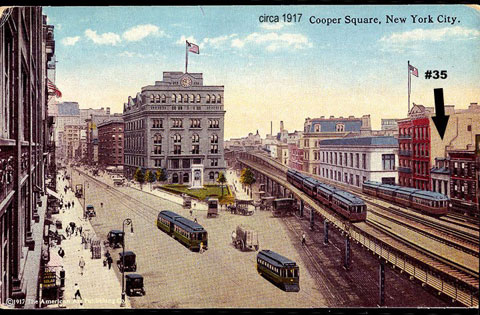

Cooper Square (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

The small federal-style building at center dating from the early 19th century may not stand much longer. It is now surrounded by scaffolding, and demolition of the roof has begun. The city has just issued a stop work order, but my guess is that it will only postpone the inevitable. The preservation groups seeking to save the character of the Bowery–this is the northern extension of the Bowery–are admirable, but rather late as you can see by the architectural context. Here is the latest news.

Presumably, the vacant lot at the corner of Third Avenue and E6th Street would be joined with the land under 35 Cooper Square to create a larger site for development.

Cooper Square in 1917

Even in 1917 few of the federal period buildings remained in this part of town.

Dorothea Lange photographs, the Museum of Modern Art — © Brian Rose

I’ve been reading Through the Lens of the City, NEA Photography Surveys of the 1970s by Mark Rice. A few comments mid-stream.

The NEA survey grants were an outgrowth of a proposal championed by Walter Mondale to commemorate the U.S. bicentennial by commissioning photographers to create a visual documentation of America along the lines of the work done by the FSA in the 1930s. That initiative died of politics, but the National Endowment for the Arts picked up the ball themselves and established the survey program that ran for several years.

In all of this, there were lots of arguments about what kind of documentary photography was desired. The work done by Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange–and many others–were recognized as the paradigm, but perhaps for the wrong reasons, or as the result of misunderstandings. Lange produced iconic images that sought to ennoble the poor farmers she photographed. And Evans was attracted to the humble vernacular structures of the south. His intellectual clarity transcended the nostalgic nature of the subject matter, and his evenhanded visual discipline provided a way to show places, things, and people which would otherwise remain invisible. Both Lange and Evans–as different from each other as they were–defined a new hybrid kind of photography that was both document and art.

The America the FSA photographers presented was a narrow view of society, intentionally of course, as part of the mandate of the Farm Security Administration. What the bicentennial project envisioned was something more ambitious, but nevertheless rooted in the FSA style of documentation, and preferably directed by someone with the strong vision of the FSA’s Roy Stryker. When the NEA took over the idea, they set up a more diverse and geographically dispersed structure. Hence there were survey projects scattered all over the United States, and unlike the rural based FSA photography, most were focused on urban areas.

From the Brooklyn Bridge, 1981 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose/Ed Fausty

By the time I was asked to participate in the Lower Manhattan project, the survey program had just about run its course. I had just completed photographing the Lower East Side with collaborator Ed Fausty, so naturally I–we–jumped at the chance to extend the project further. I don’t think we ever had a sense of what the bigger context was, that this was one of dozens of similar survey projects in other communities. In the end, ours was a failed project. There was no book or catalog, only an exhibition in Federal Hall on Wall Street that was not critically reviewed. As far as I know none of the work was placed in an archive for future research or perusal.

The work Ed and I did together or separately ended it up in boxes. It’s clear, however, in putting together the series of images for WTC, my book about the World Trade Center, that we were onto something.

Wall Street, 1981 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Although I’ve been posting photographs of the World Trade Center made in 1981, I also did lots of photographs of Lower Manhattan that did not include the constantly looming Twin Towers. And not all were sweeping views of the skyline like so many of the images in my WTC book. The picture above was made one evening on Wall Street, the spire of Trinity Church in the background echoed nicely by the icons on the Johnny Walker billboard. “Moon Can’t Be Deported” refers to Sun Myung Moon of the Unification Church who was in trouble because of tax fraud.

In the midst of the current drama in Egypt there was an article in the Times this morning about a possible merger between the Frankfurt exchange and the New York Stock Exchange. In practical terms such a merger would only highlight the increasingly international nature of finance. When I took the photograph above, trading was mostly done directly on the floor of the nearby stock exchange. But symbolically, this could be a big deal–a perceived loss of prestige–and it will be interesting to see how it plays out politically.

I am still reading Lens of the City, which tells the history of the documentary survey grants made by the National Endowment for the Arts in the late 70s and early 80s. My Lower Manhattan pictures were funded by one of those NEA grants. Comments and thoughts to come soon.

Showed my work to Robert Mann the gallery owner–someone I’ve stayed in touch with over the years. He likes my work a lot, and will keep me in mind as things go along. Meanwhile, I keep schlepping my portfolio around.

Maiden Lane from the FDR Drive, 1981 — © Brian Rose/Ed Fausty

Google street view of Maiden Lane from the FDR Drive

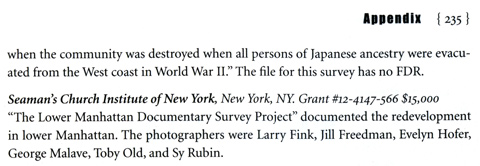

In the previous post I began discussing Through the Lens of the City, NEA Photography Surveys of the 1970s by Mark Rice. From 1978 to 1981 the National Endowment for the Arts funded documentary photography projects around the country. I was a participant in the Lower Manhattan survey, which began in 1981. In the appendix of the book is a list of all the surveys, but my name (and Ed Fausty’s) is not included among the photographers doing the New York project.

The quick explanation is that one of the original participants, Evelyn Hofer, was unable to take part–for reasons I can’t recall. Although my memory is fuzzy, I believe that Sy Rubin, another of the photographers, asked me and Ed Fausty to step in. Sy, who at that time ran the Midtown Y photography gallery–an important gallery and photographer’s clubhouse–knew us from the Lower East Side project, and was one of the organizers of the Lower Manhattan survey. I am only one of many photographers mentored by Sy Rubin, a man of great generosity with a discerning eye. Sy Rubin died a few years ago.

The Lower Manhattan survey project was eventually exhibited in 1984 at Federal Hall on Wall Street. I have not been able to find much about it on the internet, but here is an article that ran in the New York Times–and proof that Ed Fausty and I were indeed included:

It is interesting that Lower Manhattan is described in the article as humming with activity, “more so recently – when it seems never to shut down – than in past years when keyed to office hours.” It is true that artists had moved into many of the smaller commercial structures of the area, but compared to the present, the Financial District was desolate after hours and on weekends. Moreover, there are no longer any “musty, narrow byways.” Narrow streets, yes–one of the pleasures of walking the area is retracing the original Dutch layout of New Amsterdam. But musty, no. The picture above was taken from the roadway of the FDR Drive on a Sunday morning. Try doing that now.

Trinity churchyard (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

The images of the World Trade Center recently posted were not made as a specific project to photograph the Twin Towers and the WTC complex. They come from a more comprehensive look at Lower Manhattan that I did with Ed Fausty in 1981 and 1982. Ed and I–after the Lower East Side project–were asked to participate in a photographic survey sponsored by the Seaman’s Church Institute and funded by the National Endowment for the Arts. We began working together, as we had previously, but eventually finished the project separately.

The image above of the Trinity churchyard on Broadway–made in early 1981–was taken shortly after a ticker tape parade welcoming home the diplomats held hostage in Iran in the wake of the Iranian revolution. It should be noted that events presently unfolding in Egypt echo that event. An authoritarian government stands on the brink while millions demonstrate in the street. In Iran the widely unified opposition to the Shah gave rise to the religious extremism of the Ayatollahs. There is hope that things will turn out better in Egypt.

Since digging into my Lower Manhattan archive I’ve been doing a little research on how that project came about. I came across a book published in 2005 called Through the Lens of the City, NEA Photography Surveys of the 1970s. It’s written by Mark Rice, a historian, and tells the story of the short-lived grant program intended to produce a portrait of American urban life. I recall doing the project without a great deal of background knowledge on how my work, and the five other photographers involved, fit into the bigger scheme. This book will fill in the gaps.

I will comment more once I’ve read further, but first, let’s look at the appendix for a list of all the projects.

Uh-oh.

No Brian Rose or Ed Fausty. Down the memory hole again. To be continued…

I’ve put a lot more work into WTC, adding four new images and replacing a digital image with one from 4×5 film. One image is out. I’ve fine tuned the text and added a conclusion that goes opposite a 1978 image of the Twin Towers reflected in a pool of water. I think the book now has a much stronger last section.

Here is the concluding text:

Reflection

In bringing this narrative to a close I find myself equipped only with the most recent and tentative images, not yet resonant with the past. I circle ground zero with my camera dodging the drift of tourists who have made it a place of pilgrimage.

It seems sometimes, disconcertingly, that I am in the business of photographing things that precipitously cease to exist—the Berlin Wall, the Twin Towers.

New York moves forward, new towers rise, and a new generation claims the old neighborhoods. The rapidity of change rattles even the newcomers who feel history slipping through their fingers as they fumble for their keys.

Here is New York. E.B. White wrote about the city in another time of great anxiety: The sublest change in New York is something people don’t speak much about but that is in everyone’s mind. The city, for the first time in its long history, is destructible. We who live here know that all too well.

Let us then look back at what is gone–reflected towers in a pool of water. Philippe Petit on a slender wire. The names. The faces. Rising steel. The beginning of what comes after.

Smith Street, Brooklyn (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

I finally got the film back from the subway trip to Smith Street in the area near the Gowanus Canal. The image in WTC was from my small digital camera–the one above is from a 4×5 negative. Several pictures I took there are usable, but I think I will stick with this view.

West Street (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

This is the 4×5 version of an image posted earlier show 1 WTC and 7 WTC in the center.

Info kiosk with 1 and 7 WTC (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

I will update my WTC book with the images above and the two below. I’ve felt that the series needed strengthening near the end. These should do the trick.

At this point, unless something unexpected happens with a publisher, I am planning on putting this book out on Blurb in two sizes–the full size 11×13 hardcover and an 8×10 hard and softcover. The smaller books will sell for $45 to $55 as opposed to $100 plus for the larger size. From an aesthetic standpoint, the 11×13 best conveys the monumental nature of the subject, but the small book will look good, too. All three of my self-produced books will be available in the 8×10 format including Time and Space on the Lower East Side and Berlin: In from the Cold.

I’ll post a new link to the updated book once it’s ready. Link here.

Greenwich Street, Fireman’s Memorial (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Church Street, St. Paul’s Chapel Churchyard (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Earlier this week I picked up the film from my two days of shooting around ground zero. So these are scans of 4×5 film. Despite difficult snowy conditions, and a 30 second exposure for the evening shot, both negatives are razor sharp. The tall building at center of both images is One World Trade Center. The sweeping view of the site made next to the Fireman’s Memorial was, until a few weeks ago, blocked by the remnants of the Deutsche Bank building behind the blue fence to the left. I’m very pleased with these images and intend to work them into the WTC book. Stay tuned for several more images.

It’s taken me a while to get these up because I had jury duty–two days on call–didn’t get picked. A jury of your peers in Manhattan can be a pretty rarefied group. A hundred of us were taken into a courtroom for jury selection and 18 were interviewed by the prosecution and defense attorney. You were asked to respond to basic questions about career, education, and family. 17 of the 18 in that first group had college degrees. Many had masters degrees. The jury was selected before I had a chance to be interviewed. It was an armed robbery.