Williamsburg, Brooklyn — © Brian Rose

Without comment.

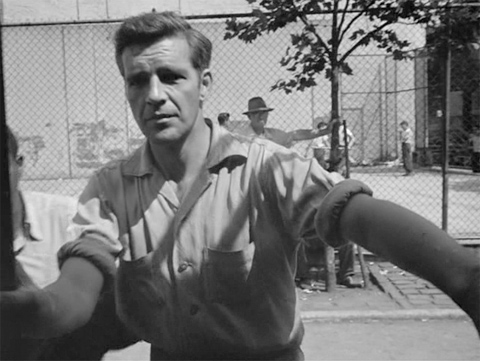

Houston Street and Bowery 1957 — from the film On the Bowery

In the previous post I wrote about seeing On the Bowery at Film Forum, and I connected several film locations with contemporary views of the same places. One of the spots that jumped out at me was the corner of Houston and Bowery where the protagonist in the story, Ray Salyer, goes in search of a day’s work. In the screen capture above, he walks up to the window of a truck–we see him from inside–and behind him is a chain link enclosed handball court with several people playing. That playground, and other open spaces along Houston, was created in the 1930s when the buildings on the north side of the street were demolished, displacing thousands of tenement dwellers, to allow for the digging of the IND subway line.

Watching the film, I suddenly realized that the wall in the rear is the same one that Keith Haring painted on in 1982, and which was used to recreate his mural in 2008. Many other graffiti artists have also worked on its surface. The original wall shown in On the Bowery is still there, but presently boxed in, now being used to showcase a changing array of artists.

Unfinished Kenny Scharf on the Houston/Bowery wall — © Brian Rose

The photo above was taken from approximately the same position as the scene in On the Bowery. But there is a major difference, and it took me a while to figure things out. In the film there is a broad sidewalk and full depth handball court on the north side of Houston. Today, as you can see above, a swath of sidewalk and about four feet of gravel is all that separates the street from the wall. What happened is that Houston Street was widened along the north side turning a four lane undivided street into the monster thoroughfare that it is today.

From the Times:

THE widening of the Houston Street roadbed, to two 45-foot-wide roadways separated by a narrow mall, did not start until 1957. The Times reported that ”new black-on-yellow street name signs will replace the outmoded blue-on-white signs,” referring to the old luminous enameled signs that occasionally show up on eBay. The new Houston Street, an eight-lane crosstown artery, was opened in 1963, just before the area south of Houston Street began to emerge as an artists’ enclave.

Unfinished Kenny Scharf on the Houston/Bowery wall

— © Brian Rose

Although the concrete handball court wall remains (a historic artifact encased in plywood), the Ray Salyers of the world no longer congregate at Houston and Bowery looking for work.

Film Forum, Houston Street — © Brian Rose

On Wednesday I walked over to Film Forum on West Houston to see On the Bowery, a movie I had heard about over the years, but never seen. It was recently re-released in a newly restored print. On the Bowery was made by Lionel Rogosin in 1957, and depicts three days of life on what was at that time America’s most infamous skid row. It is a hybrid film–part documentary, part directed narrative–and its characters were played by actual denizens of the Bowery, people that Rogosin had met over several month’s research before the movie was shot.

It remains, 53 years after its making, a cinematic tour de force. Rogosin worked with an extraordinary team, especially the cameraman Dick Bagley, and the editor Carl Lerner, who also worked on classic Hollywood movies such as 12 Angry Men. The story is minimal–a young man arrives on the Bowery with nothing but a suitcase and a powerful thirst for alcohol. He meets several regulars at a bar, ends up sleeping on the street, gets robbed, and is helped by his thief, a sly but sympathetic Bowery old-timer, who gives him some of the money he got from selling the newcomer’s stolen pocket watch.

The Bowery between Houston and Prince — still from On the Bowery

Most of the film was shot on the block between Houston and Prince Streets, and the Confidence Bar and Grill (above) once stood at the point where Stanton Street meets the Bowery. This is my corner of the world–my office/apartment is on Stanton just off the Bowery. When I first arrived in New York in 1977, I lived on East 4th Street five blocks north. The Bowery was still skid row in those days, and remained a seedy final destination for untold thousands until well into the 1990s. It is skid row no longer as high end restaurants and galleries supplant the cheap hotels and restaurant supply stores that dominated the area, some of which of can be seen in the film.

The Bowery between Houston and Prince — still from On the Bowery

The Bowery between Houston and Prince — similar view as above

— © Brian Rose

For nearly 75 years the Bowery was darkened by the elevated tracks running its length and on up Third Avenue into the Bronx. But by 1957 the steel viaduct was no longer used and was in the process of being demolished. In Rogosin’s film the hulking structure of the El lends many of the scenes a closed off subterranean feel. The stretch of Bowery buildings shown above still stands, almost as ragged looking as before, but without the encompassing gloom and claustrophobia.

The Bowery between Houston and Prince (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

A few years ago I took the picture above with my view camera. The building at left with the cutouts attached to the facade is 254 Bowery, the former location of the Confidence Bar and Grill. In the movie still you can see the word Paragon on the building next door. That’s the same building above from around 2005.

The Bowery between Houston and Prince — © Brian Rose

But those buildings are gone now. The site was cleared for the construction of a luxury hotel, a project that died when the economy collapsed in 2008. The lot has sat vacant since then, but I read recently on Curbed, the architecture and real estate blog, that a new project may be in the works.

The Sunshine Hotel, Bowery and Stanton Street — still from On the Bowery

Near the end of On the Bowery, the lead character, Ray Salyer, goes to the Bowery Mission with hopes of staying sober, but after being preached to and finding he has to sleep on newspapers spread on the floor, he heads back out to the street. In a stunning montage, as he drinks himself into a stupor, he and the other men get louder and louder, epithets are hurled, fisticuffs break out–however ineffectual–and the scene unwinds in a chaotic drunken din. Salyer, with a woman on his arm, stumbles from the bar and heads for the Sunshine Hotel, where he slaps her away (seen above). The Sunshine is one of the last Bowery flophouses, right next door to the New Museum, still home to a dwindling assortment of derelict men, a no vacancy sign on the door, the end in sight.

The film closes with another montage, as astonishing as the barroom scene. As Salyer stands on the Bowery contemplating his next move, a sequence of closeups of faces is shown, each held on the screen a few seconds. Each visage a portrait of utter dissolution, each line and crease, stubble of beard and trickle of dried blood, rendered vividly, dispassionately.

There is no redemption suggested in this ending, and even though On the Bowery was hailed by many, and nominated for an Oscar, its bleak outlook was not generally welcome in the propagandistic 1950s. Rogosin’s On the Bowery shares the unsparing outlook of Robert Frank who also revealed the underside of American society in his book The Americans. Frank’s documentary approach has been widely absorbed by several generations of photographers, but Rogosin’s method, combining documentary and staged reality, remains under appreciated by those of us schooled in the cinema verite style.

Seeing the movie, and then walking back to my office right where the film was made, a neighborhood already changed, undergoing even more radical transformation–it’s quite a lot to reflect on.

Smith Street Station, Brooklyn — © Brian Rose

If you’ve been following this blog, you know that I have been piecing together a series of images that relate directly or indirectly to the World Trade Center. A couple of years ago I came across a Twin Towers mural near the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. I did a quick snapshot of it with the intention of returning to photograph it with the view camera. This morning, I finally got back there.

I took the F Train, which emerges from underground just past Carroll Gardens in Brooklyn. The tracks are carried high up on a massive steel bridge that spans the Gowanus Canal, an infamously polluted industrial area that has become a haven for artists, and as a result, ripe for upper middle class development. With the downturn in the economy, however, and given the cost of cleaning up the area, not much has happened. The Gowanus is still a fabulously gritty blue collar lowland between Carroll Gardens and Park Slope, two of Brooklyn’s most desirable neighborhoods.

WTC mural on Smith Street, Brooklyn — © Brian Rose

Across the street from the subway entrance is a somewhat forlorn car wash decorated with tattered red white and blue streamers–but across Smith Street a row of old houses with slanted roofs and dormer windows is being renovated. The WTC mural with its flag motif is painted on the side of a small building next to a chain linked vacant lot. Across the street from the mural is a heating oil depot where trucks drive up and fill their tanks. A glass enclosed command post overlooks the operation, and when I set up my camera on the asphalt just off the sidewalk, I was informed by a stern voice coming over a loudspeaker that I was standing on private property. I managed to get off one shot with my 4×5 camera.

Smith Street, Brooklyn — © Brian Rose

Retreating from the oil depot, I went across the street and set up the camera at an oblique angle to the mural. Promptly, a gruff voice barked accusingly, “Are you taking a picture of my truck?” I jerked my head toward the voice, and saw a grinning face sitting behind the wheel of a truck with a battered container mounted behind. He was kidding. I told him I just got yelled at by the guys across the street, and was a little jumpy. We chatted a bit, he smiled for the camera and roared off.

WTC mural on Smith Street, Brooklyn — © Brian Rose

Here is the image taken from “private property.” And while I think the 4×5 shot will be good, I really like these two white trucks caught left and right in the frame. You don’t see it the pictures, but there were lots of people walking around–some pretty damaged people it seemed to me–probably coming from some sort of social services facility nearby. Others were standing around under the subway viaduct waiting for a bus, or perhaps, waiting to be picked up as day laborers.

One guy started talking to me, asked me what I was doing. I pointed to the mural and told him I was photographing WTC things. He asked me about the mosque/cultural center proposed for downtown near ground zero. I looked at him more intently–he seemed to be Hispanic–I didn’t ask him where he was from. He had just seen an article in the paper. The group building the center was applying for money meant to support projects around the Word Trade Center site. The right wingers were agitating again. He wanted to know what I thought about it. I said, ” I know Christians, Jews, and I know Muslims. This is New York. I think they should be able to build their center. He said, somewhat to my surprise, “I’m with you.”

Greenpoint, Queens (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

This is my America, from my heart, and by my heart. I give it now to my children and grandchildren, and to yours, so they will always know what it was like in America when people were free.

–Sarah Palin (from the introduction to her forthcoming book America By Heart)

Delusional and dangerous.

Lafayette and Bond Street — © Brian Rose

Everybody knows that the dice are loaded

Everybody rolls with their fingers crossed

Everybody knows that the war is over

Everybody knows the good guys lost

Everybody knows the fight was fixed

The poor stay poor, the rich get rich

That’s how it goes

Everybody knows

Everybody knows that the boat is leaking

Everybody knows that the captain lied

Everybody got this broken feeling

Like their father or their dog just died

Everybody talking to their pockets

Everybody wants a box of chocolates

And a long stem rose

Everybody knows

Song lyrics by Leonard Cohen

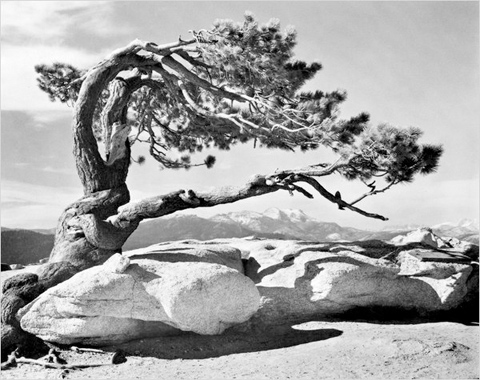

Photograph by Ansel Adams

By now you have probably heard about the controversy surrounding a bunch of negatives of Yosemite National park attributed to Ansel Adams. Rick Norsigian from California bought them at a garage sale for $45 and now a dealer is selling them for $200 million. Now there’s more.

From the New York Times:

Then an 87-year-old woman surfaced to say that she had three prints that looked a lot like Mr. Norsigian’s images — one was hanging in her bathroom — and that they had been shot, she said, not by Adams, but by Earl Brooks, her uncle, who was a little-known photographer.

Now Melinda Pillsbury-Foster says her grandfather Arthur C. Pillsbury, a well-known photographer of the period, should be added to the list of possible creators of the images of Yosemite park and the Northern California coast that Mr. Norsigian bought a decade ago.

It seems they all photographed the same subjects with view cameras around the same period of time–Adams, of course, being the more famous by far. As with the story of the newly uncovered Jackson Pollocks–or forgeries–the interest is all about money and the potential undermining of a brand jealously guarded by dealers and estates. None of this has anything to do with the art itself.

Yosemite Valley by Ansel Adams

Which is where I will get myself in trouble with some folks. I’m sorry, but some of us long ago became photographers because, among a few other more positive reasons, we hated Ansel Adams’ photographs and the whole heroic landscape aesthetic. I am well aware that Adams did a lot to put photography on the map, and that his pictures were important to the creation of the National Park system. But there was never a more stultifying influence on photography than Adams and his zone system, and the attendant cult-like worship of the silver print. Moreover, his depiction of America as a land of untrammeled beauty was always a lie–even before we realized how rapidly our environment was being despoiled.

Yosemite Valley by Carleton Watkins

Before there was Adams, photographers like William Henry Jackson and Carleton Watkins revealed the majestic scope of the American west to the public. Their images, while meticulously and artfully composed, were as much utilitarian as aesthetic. In contrast, Adams’ images–especially printed in almost surreal high dynamic range–are bombastic, theatrical.

Adams is popular because his work offers escape rather than engagement. His self-consciously composed images of a pristine American landscape were nostalgic and retrograde the second they were taken, and in today’s political climate of global warming deniers and “drill baby drill” extremists, Adams’ imagery supports, however unintended, an anodyne version of American ideals.

It seemed that way to me in 1970 when as a teenager I first started taking pictures–well before the “new topographics” rejiggered our way of seeing the landscape–and nothing since has changed my opinion.

West 4th Street subway station — © Brian Rose

I came across a photo of mine in the West 4th Street subway station–part of a large installation called “Made in New York,” which features the work of New York City based architects. It’s the image on the top row, second from left, of the Holocaust Center at Queensborough Community College by TEK Architects.

Here’s an article about the project. And another.

I went to PS1 in Long Island City to the New York Art Book Fair, an immense bazaar of independent publishers and self publishers. It was overwhelming. Thousands of books and a crowd exuding off-the-charts coolness. I felt I was in some parallel universe, a self-contained world of hyper-awareness and solipsism. Lots of great stuff I’m sure, but it all began to diminish before me, like looking through the wrong end of a telescope, smaller and smaller and smaller.

So, I did what I always do when confronted with such situations–I took pictures. First a security guard leaning against a glass wall. Then out the window, the Citibank tower aglow. Then in the courtyard, a concrete wall and rosy sky. Through the museum entrance and into the street I followed the last shards of sunlight bursting in a kaleidoscope of graffiti painted walls, I walked home toward the G train past a contructivist mashup of shapes and letters.

A photographic impromptu done while documenting the Louis Kahn bath house and day camp pavilions. The series starts with a view of the pavilions and then takes in the grove of trees, sheds, and various objects that dot this nondescript, but oddly compelling landscape.

© Brian Rose

© Brian Rose

© Brian Rose

© Brian Rose

© Brian Rose

© Brian Rose

© Brian Rose

© Brian Rose

Fall little league in J.J. Walker Park — © Brian Rose

The liberal marxist San Franciso Giants beat the right wing brownshirt Texas Rangers last night in the World Series. Such is the state of our politics on this election day. Somehow, I think we are all going to come out of this election as losers.

Louis Kahn Bath House, Trenton, New Jersey — © Brian Rose

As I suggested in an earlier post about the Kahn bath house, there is more to the project than the cinderblock changing rooms that most people are familiar with. The photo above shows the central courtyard of the bath house with floating pyramidal roofs resting on hollow piers, which act as separate spaces–as baffles for access to the changing rooms, and as storage and mechanical spaces. The complex is rigidly symmetrical. Four square rooms and a square central court with a circle inscribed in the pavement.

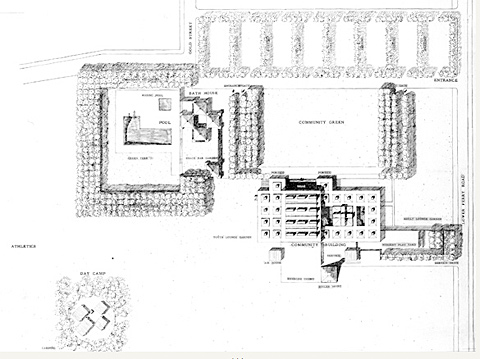

Kahn was originally hired to create a campus for the Jewish Community Center, which was to include a pool/bath house, a community building, and a day camp for outdoor activities. Only parts of it were carried out. In the plan above you can see the bath house and pool in the upper left. At the lower left is a collection of small pavilions that comprised the day camp. These were built, and despite falling into disrepair, survived to be restored as part of the overall project headed by FMG Architects of Princeton.

Here is a historic view of the pavilions in use. The columns were made of terracotta pipe material filled with concrete. My understanding is that the outer material soon cracked and was stripped off leaving the bare concrete pillars. When I photographed the bath house last February the day camp pavilions were in ruins.

Kahn day camp pavilions, February 2010 © Brian Rose

Kahn day camp pavilions, October 2010 © Brian Rose

The day camp stands perhaps 100 yards from the bath house, and the four rectangular pavilions are arranged asymmetrically inside an earthen circle. The pavilions were meant as open air and indoor space in which various activities could take place. Today, there is an amphitheater adjacent, and a collection of small sheds or play houses. The terracotta columns have been recreated.

Kahn day camp pavilions, October 2010 © Brian Rose

The pavilions while made from utilitarian materials with a very prosaic recreational purpose, evoke an ancient temple complex set in a clearing, raised slightly on a plinth. Moving through and around the pavilions provides a constantly changing series of spacial and visual relationships.

Around the pavilions, the day camp has built a collection of small huts, which I imagine are club houses, or play houses for kids. Their toy-like presence echoes and contrasts with Kahn’s serious temples of play nearby.

The Louis Kahn bath house, now restored, consists of two groupings of buildings–the pool complex and the day camp–juxtaposed across an open field. In these two extremely modest constructions, Kahn, early in his career, experimented with the architectural elements that would serve as the basis for his most ambitious work. For the first time in many years, these two pieces of Kahn’s unfinished site plan can be viewed together, in relation to one another.

I mentioned a few months ago that I was expecting the Museum of Modern Art to acquire two of my photographs. It is now official. The acquisition committee approved the purchase. This is not the first time I have sold prints to the museum. They have previously acquired images from my Lost Border/Iron Curtain series. But, I am pleased that they have now added more recent work from Berlin and Amsterdam.

Mauerstrasse, Berlin (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

From the series Berlin: In from the Cold

Since the Wall came down I have been returning to Berlin every couple years looking at developments in the former border zone, and venturing beyond to places and themes that resonate with my earlier work. Berlin, while having undergone two waves of rebuilding–first after World War II, and then after the Cold War–remains a city of scars, of vacant land and rough edges, in which history is laid bare.

In the photograph above, the layering of eras, architectural styles, materials and objects, conspire in an almost bewildering jumble. The location is but a few steps away from Checkpoint Charlie and the trace of the former Berlin Wall. As I was walking around the area, I discovered an opening to an inner courtyard–a Hinterhof, common in Berlin–and came across this scene.

There are any number of ways I approach things as a photographer. Sometimes, the subject–a building or object–demands to be respected as is, as opposed to being integrated into a willful composition. It is the composition. One of the things I’ve learned from my experience as an architectural photographer is that sometimes–often, perhaps–one has to remain subservient to the subject. And as an artist/photographer I realize that it is not necessary, nor is it advantageous, to attempt to reinvent the medium each time I set up my camera and release the shutter.

There are also times when the subject is illusive. It may be contained in the inchoate envelope of a space, or found in the interstices of a barely recognized structure. For me, the spacial world is always a multidimensional reality, not simply a compositional layering of one thing upon another. I see things rather as a matrix, a situation comprised of any number of anecdotal or accidental relationships. The photograph above is that kind of image. In simpler terms, it’s about how all that stuff hangs together visually–about nothing–and about something essential that defines, in this case, Berlin.

Jewish Cemetery, Amsterdam (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

For 15 years, while living in Amsterdam, I photographed the changing periphery of the city and its less determined edges. I call the series Amsterdam on Edge, which expresses not just the physical location of the photographs, but the psychological condition of a society deeply unsure of its identity and its future in a multicultural Europe.

In exploring the outskirts of the city, I often took trams to their end points, or drove to obscure areas along the freeways. One unexpected discovery was a Jewish cemetery bisected by a train viaduct and hemmed in by a freeway and high-tension power lines. Many of the gravestones were marked Westerbork, the name of the camp that served as a way station en route to Auschwitz and other Nazi camps. Nearly 90,000 Jews, more than 10 percent of the population of Amsterdam at that time, were killed.

Williamsburg Bridge and East River Park — © Brian Rose

I went to East River Park to my son’s soccer game yesterday evening. 107 years ago when the Williamsburg Bridge was opened, this area, just to the south–called Corlears Hook–was comprised of docks, factories, and tenement housing. 19th century Corlears Hook had an unsavory reputation due to its thieves and prostitutes–hence the term “hookers.”

Today, the docks have been replaced by parkland, and towering housing projects dominate the area.

The first thing that has to be done is secure the border. . . East Germany was very, very able to reduce the flow. Now, obviously, other things were involved. We have the capacity to, as a great nation, secure the border. If East Germany could, we could.

— Joe Miller, Republican candidate for U.S. Senate, Alaska

Heinersdorf, Germany on the Iron Curtain border, 1987 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Just in case anyone is confused. The Iron Curtain split towns, divided families, and crushed lives. It was the nuclear trip wire between east and west, the real and symbolic expression of the authoritarian ideology of the Soviet Union and its proxy states. It was designed not to keep people out, but to keep people in.