As a landscape photographer working in color with a view camera I have always had enormous respect for Richard Misrach. I own several of his books, and regard him as a pioneer in the field. After years of sticking to a reliable, if predictable, way of working, Misrach has recently experimented with different points of view–the beach series–and now, has begun exploring digital photography, both with camera and print.

Photograph by Richard Misrach — from On the Beach

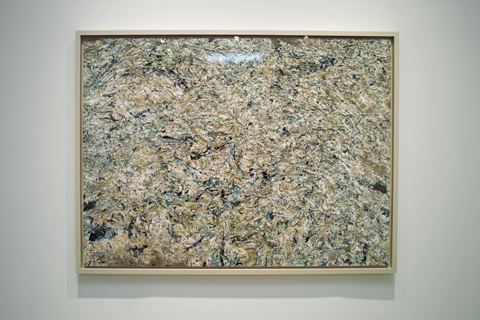

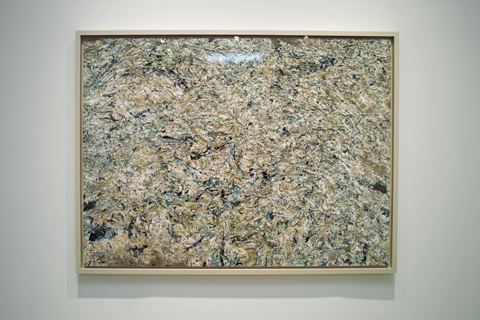

The current show at Pace Wildenstein presents a series of large scale photographs printed as negative images, that is, inverted in Photoshop. Going to the gallery I had trepidations about the work having seen a few small images on the Internet. My first reaction on seeing the actual prints, however, was that I found them seductively beautiful, especially at such a size. And I was not troubled by the trick of inverting the images.

Since leaving the gallery, I’ve been having second thoughts, and I’ve gone back and forth on my opinion of the validity of the “the trick.” It’s not that this kind of thing is unheard of in the history of the medium. On the contrary, such experimentation has long been a part of the development of photography from Man Ray to recent color enhanced views of the surface of Mars.

Richard Misrach show at Pace Wildenstein — © Brian Rose

Mouse over for effect, click through to larger image.

Looking at my snapshots of the exhibit I began thinking that the prints were essentially inverted versions of typical Misrach scenes of the American west, no more, no less. The inversion gave them an otherworldly appearance, but really, they were less strange once the initial disorientation wore off.

And then suddenly I thought, what if I flipped the images in Photoshop. What would they look like? First, I inverted whole snapshots, but then just the images within their frames. The startling result can be seen by mousing over the snapshots posted above and below.

Richard Misrach show at Pace Wildenstein — © Brian Rose

Mouse over for effect, click through to larger image.

I’ve decided, for the moment, that I prefer the more abstract images because they are less recognizable as landscapes, but I’m still wrestling with the whole thing. As gorgeous as the prints are, I’m more and more convinced that the negative effect is too much a Photoshop product, a passing infatuation with digital wizardry. Very simplistic wizardry at that. And I’m put off by the press release language: Misrach’s newest pictures – the majority of which are made entirely without film – mark a radical shift from his past work and herald a new era in photography’s history.

Entirely without film. Wow.

Richard Misrach show at Pace Wildenstein — © Brian Rose

Mouse over for effect, click through to larger image.

I still really love the image of stars in motion, the first picture one sees entering the gallery. The sky is white and the streaking stars are black. And I like the “Pollock” evocation above, which is disorienting without being inverted. It’s positively a positive.