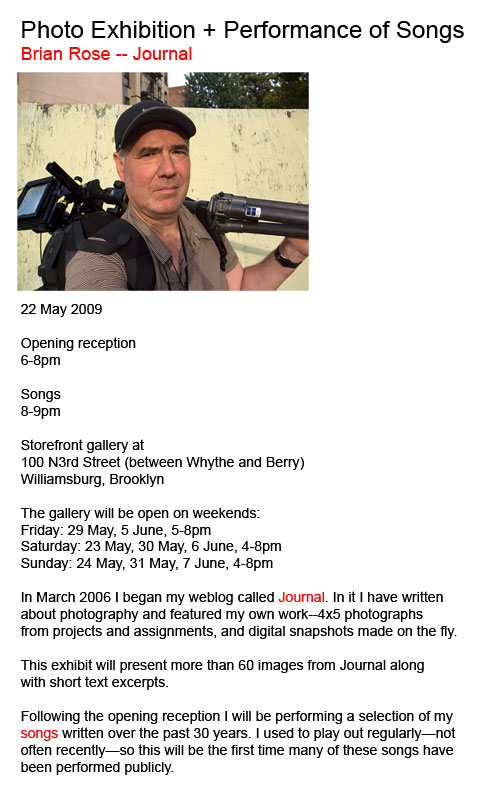

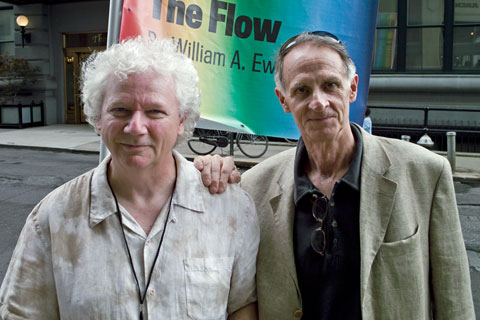

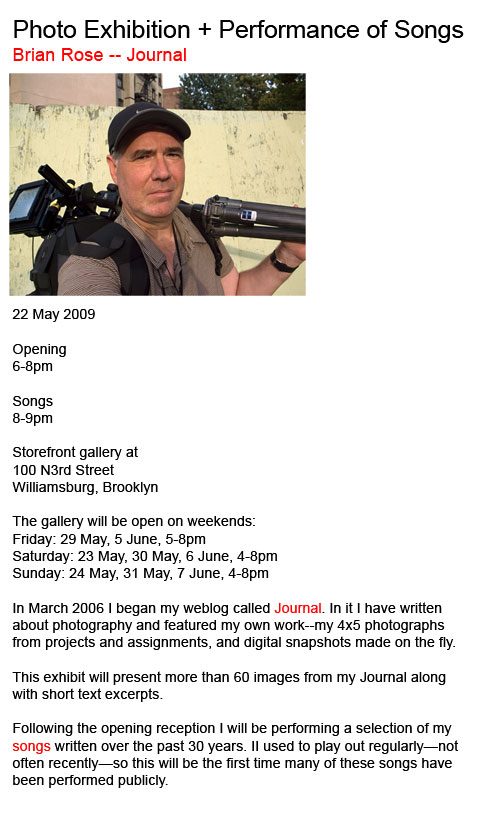

The opening and performance at the gallery in Williamsburg went well. Scroll down for more information about the show and gallery hours. A decent crowd considering it was the beginning of the Memorial Day weekend. I performed a batch of my songs after the reception, the first time I’ve played in public in several years. I did around eight songs, some early ones from the late ’70s, and a few from recent years. I was happy to see Cervin Robinson, the architectural photographer, as well as music friends Greg Anderson and Jim Allen.

Under the Manhattan Bridge in Dumbo, Brooklyn

A few additional comments from the New York Photo Festival. I think the most provocative work in the show was by Danish photographer Jacob Holdt, a sort of outsider artist, whose work has generally escaped notice in the art world. A couple of years ago his photographs made in the early 1970s while traveling around the US were published by Steidl. But his work has not been seen much on this side of the pond.

Photo by Jacob Holdt

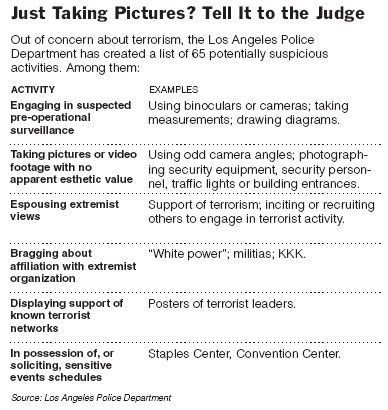

Hitchhiking around the country, Holdt hung out with and lived with people of all walks of life, but particularly the down and out. His photographs show the squalor of urban and rural life in the ’70s, violence, guns, racism. He even befriended member of the KKK, and photographed cross burnings. Holdt presents his work as political activism, and in fact, he has given lectures and slide shows for years since making the photographs. At the festival his slides were shown on several old-fashioned carousel projectors, their fans whirring, the slides click clacking into place.

Photo by Jacob Holdt

There is zero art gloss to his photographic method–the images are crudely powerful. Disturbing. And although I think the attention he is now getting is legitimate, I am somewhat suspicious of the high culture assimilation of his work. By all means spend some time on his website. Where does work like this fit into the history of photography and social documentation?

Photo by Jacob Holdt

William Ewing, one of the curators of the festival, argues that the photo history canon of the past few decades needs to be shaken up. That older photographers like Holdt have been overlooked, and that younger photographers from all corners of the globe aren’t getting the attention they deserve. I am sympathetic to his curatorial quest, but remain uncertain where to place someone as strange and insistently didactic as Jocob Holdt. Perhaps, he is best left outside the canon. Someone to be dealt with on his own terms.

Dumbo, Brooklyn