Without comment.

New York/Cervin Robinson

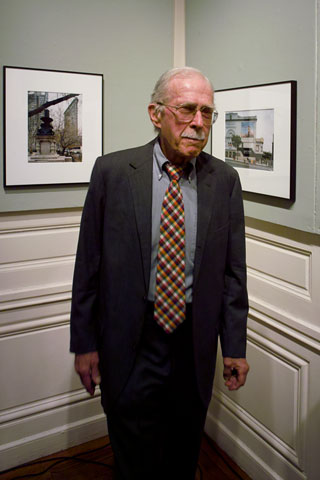

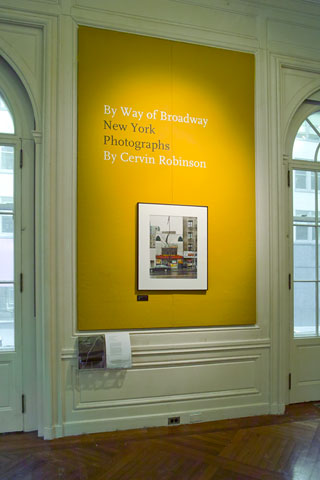

A few weeks ago I went to Cervin Robinson’s opening at the Urban Center Gallery. It was a crowded affair, and not a good moment to look at the photographs. So, yesterday I returned to the exhibit, By Way of Broadway, and spent some time with the pictures.

The gallery consists of two large rooms of the former Villard Houses, which now are home to the Municipal Arts Society and the Urban Center bookstore. The Palace Hotel uses part of the original buildings as well, and its bland tower looms over the entry courtyard seen above. How that happened is a story in itself.

Cervin Robinson at the Urban Center Gallery — © Brian Rose

Despite the use of the rooms as a gallery, their historic appearance has been preserved. But that means that any exhibition mounted has to contend with wainscotting and other architectural details. It’s beautiful, but not always the most flexible space, much like the old ICP galleries, which were housed in a historic mansion on East 94th Street.

Urban Center Gallery — © Brian Rose

On one wall of the gallery (pictured above), a fireplace has been covered, and a large mirror stands above it. Casement doors connect the gallery to the main lobby. It’s a gracious and dignified space, and works pretty well for Cervin Robinson’s equally well-mannered photographs.

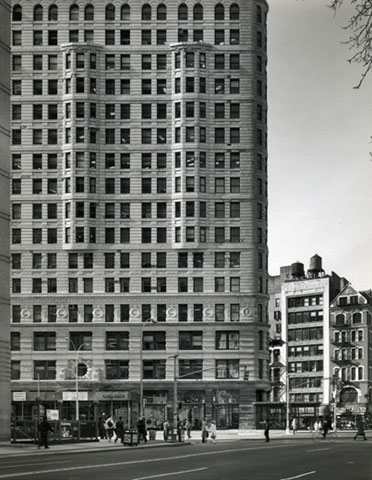

Cervin Robinson, the Flatiron Building

Robinson is one of a handful of photographers who defined what is understood today as architectural photography. He is in the company of the late Ezra Stoller, and Julius Shulman, who is still with us in his nineties. Dutch photographer Jan Versnel–not well known in the United States–was another of this select club. Together, they not only helped establish the profession of architectural photography, they also made the images that form our collective awareness and recognition of important works of architecture.

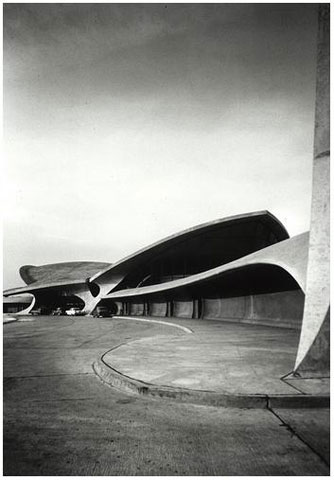

TWA Terminal — photo by Ezra Stoller

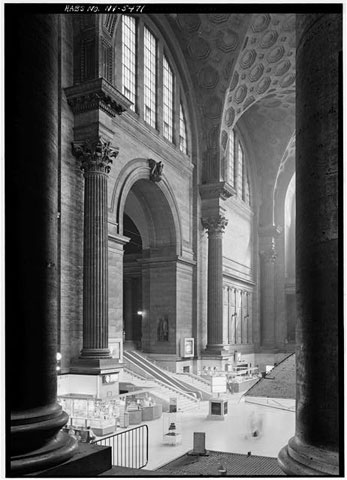

When we think of Saarinen’s TWA terminal, we see it through the pictures that Stoller made of that swooping structure. When we think of the Case Study houses of Southern California we see them through the photographs of Julius Shulman. And when we think of the innovations of Louis Sullivan, or remember the much mourned Pennsylvania Station by McKim Mead and White , we do so with the help of images made by Cervin Robinson.

Pennsylvania Station — photo by Cervin Robinson

The show at the Urban Center, however, is not about Robinson’s commissioned work or extensive book projects. This series of images focuses on Broadway, Manhattan’s slightly meandering street that runs from tip to tip of the island. It’s one of America’s principle thoroughfares–Wall Street lies perpendicular to it, Times Square is formed by its vector across Seventh Avenue, and it brushes the corner of Central Park at Columbus Circle. Further uptown it slices past Lincoln Center, bisects the campus of Columbia University, crosses 125th Street in Harlem, eventually leaving Manhattan and continuing up through the Bronx and further upstate as route 9.

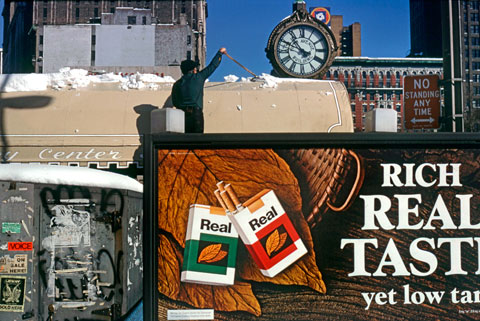

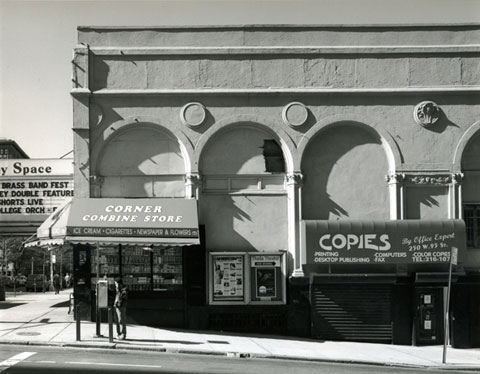

Broadway — Cervin Robinson

Robinson’s photography can be difficult to write about because there is so little artifice in it. One of the things architectural photographers learn is that they have an obligation to the building they are documenting–that their own style or signature as a photographer must take a backseat to allowing the architectural object to come through. Robinson brings this same self-effacing approach to his personal work in the streets of New York.

Broadway — Cervin Robinson

Here the object is more diverse, multifaceted, but Robinson finds in the jumble of the city points of attention, organizing elements in an otherwise chaotic scene, and always, the beauty of structures both grand and humble. In the years he has been photographing Broadway, many of those structures have disappeared, preserved only by his view camera. And Robinson returns dignity to lost art deco gems, obscured by signs, robbed of their original functions.

Broadway — Cervin Robinson

Robinson does this without a note of lachrymosity, though we may weep for the things he reveals. Above all, however, Robinson celebrates the richness of the architectural heritage of the city–and although he remains even handed in his attention to the cityscape new and old, his eye lingers on the crafted masonry facades of pre-war New York. But despite Robinson’s objective acuity, it is his street–he lives on Broadway–and in the end By Way of Broadway is a personal project, the linear path of a life devoted to describing the city, the nature of place, and the ennobling power of architecture.

The entire exhibition can be viewed here.

New York/Midtown

New York/Into the Sunset

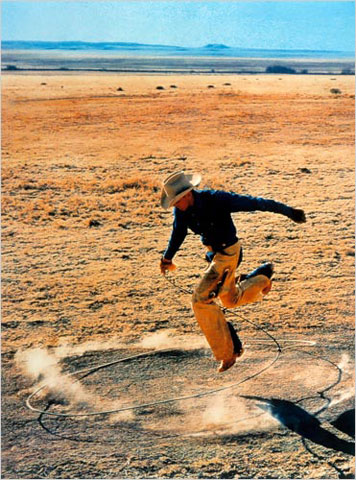

Into the Sunset at MoMA begins with one of Richard Prince’s cowboy appropriations, which is meant as a signal that this exhibition about photography and the west is meant to challenge conventional assumptions. I’ve visited the show twice, which is chock-a-block with famous images by famous photographers, but feel oddly ambivalent about it all.

Richard Prince (original by Jim Krantz)

For me, Richard Prince is old (10 gallon) hat, the art equivalent of AIG credit default swaps and other toxic paper. The system needs to be purged, the debt retired. There’s too much about “Into the Sunset” that calls up familiar critical tropes and cliches. It’s all true that early photographers romanticized the west, that Manifest Destiny was evil, that the landscape has been scarred by sprawl and pollution, that the history of the west has been full of charlatans, drifters, losers, religious zealots, pornographers, etc., and that we still cling to heroic images of cowboys used to sell everything from cigarettes to 4×4 trucks.

I guess I want a different narrative–but if that’s not possible, at least a different take on the narrative. One that sneaks up on me a little, gets me to think about things less rectangularly than the bed of that 4×4 truck. I think I’m looking for an exhibition that gets beyond the flat files of MoMA’s photography department. I’m not sure what that exhibition would look like, or who the photographers would be. Probably some of the photographers in the exhibit, and probably a whole lot not there. More photography, fewer curatorial checked boxes.

Museum of Modern Art — © Brian Rose

At the entrance to the exhibit right in front of Richard Prince’s “plagiarized” cowboy–a photograph of another photograph–there is a “photography is not permitted” sign. Time to saddle up and get out of Dodge.

New York/Pickup Basketball

This time I went out with the view camera, and shot about 10 sheets of film. I want the detail of the 4×5. Ideally, I’d get a high megapixel digital camera–bigger than any of the dslrs–but they are expensive even to rent. These pics are from my Sigma DP1.

Between games.

New York/Helen Levitt

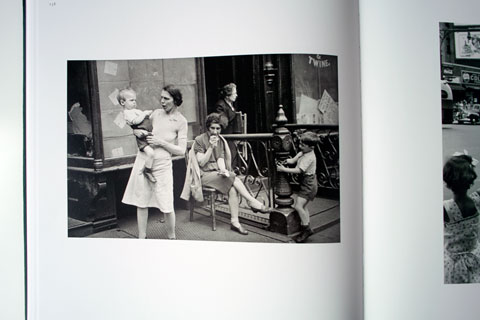

From the book Helen Levitt published by powerHouse Books

A lot has been written in the past week since Helen Levitt passed away at the age of 95. I have just a few comments and an anecdote.

Helen Levitt was the quintessential street photographer. Her work was lyrical, joyful, even as she focused on New York’s poorest neighborhoods. Her streets were filled with people and activity–above all children who grew up outdoors in the city–no longer the case today. Her work exhibited both affection for picture making and for humanity seen without sentimentality or condescension. And while she sought candid moments in the street, her subjects, while momentarily exposed, were not unduly robbed of dignity.

When I began photographing the Lower East Side in 1980, I was well aware of Helen Levitt, and knew that she had often prowled the streets of the neighborhood. One day, while walking somewhere in the vicinity of Orchard Street, or perhaps Ludlow, I saw a small, older woman in a mousy gray raincoat taking pictures. She wore a hat. She moved slowly, but cat-like. She carried a Leica. It was Helen Levitt.

New York/Houston Street

New York/Phillip-Lorca diCorcia

Phillip-Lorca diCorcia at David Zwirner Gallery

I first met Phillip-Lorca diCorcia years ago at My Own Color Lab, a rental lab where a lot of art photographers were making their own prints. I liked what he was doing, but only saw his work in bits and pieces, and didn’t realize until later that his career was beginning to take off.

Although I’ve had mixed feelings about the recent spate of staged or semi-staged photography, I’ve always appreciated diCorcia’s hybrid approach–working in the street or landscape, but introducing a theatrical element like lighting or posing of individuals in situ. Sometimes his subjects are isolated, other times engaged with the photographer.

Phillip-Lorca diCorcia at David Zwirner Gallery

DiCorcia’s recent show–Thousand–at David Zwirner Gallery represents 25 years of his work–outtakes, snapshots, tests–some from his various projects, others of family, friends, travel, everyday life. For all that time, diCorcia made medium format size Polaroids, which are placed along a small shelf wrapping around the gallery walls.

It’s the first time I needed reading glasses to see a photo exhibit, and I found myself moving continuously left to right, ocassionally pausing to look at a particular image, then resuming my sideways movement.

Phillip-Lorca diCorcia at David Zwirner Gallery

The images vary from icons of diCorcia’s work to throw-away snapshots and blurry bits of color and light. Seeing all 1,000 images, as I did, is hypnotic, even a little dizzying and disorienting. But I found the process of taking in so many tiny images quite compelling–a life’s work laid out end to end, though not chronologically. Individual images jump out jewel-like and precise. Passages, like music, emerge out of the linearity, blurriness and sharpness alternate. Familiar faces repeat, including diCorcia’s own.

New York/Pickup Basketball

New York/AIPAD

Went to AIPAD (Association of International Photography Art Dealers) show at the cavernous Armory at 67th and Park Avenue with friends Art Presson and Eve Kessler.

Hard to come to any conclusions about the direction of photography from the multifarious offering on display. There was plenty of contemporary photography, but old masters reigned. The scuttlebutt is that super-sized prints are out–so yesterday, pre-recession.

The Andrew Moore picture, above, used for the show’s poster advertising hung adjacent some tables where we had lunch. An arresting image–a wide angle view of Times Square in all its intensity–I was bemused by the extreme saturation, especially in the yellows, and the hyper sharpening applied overall. The Pandora’s box of Photoshop. In contrast, was a beautifully rendered recent print from Joel Meyerowitz’s Cape Light series. It had all the lushness one would want, but retained a softer, more naturalistic quality.

New York/The Bowery

New York/Cervin Robinson

Went to Cervin Robinson’s opening at the Urban Center Gallery in Midtown. Cervin, who lives on Broadway, has photographed Manhattan’s singular, slightly meandering avenue for many years. Thirty photographs are on display–black and white images and more recent color–all made with a view camera.

I will write more about the exhibit once I’ve had a chance to revisit and spend some time with the pictures.

New York/The Bowery

New York/Stadiums

Opening day is not far off for New York’s two teams each with new stadiums. Both promise to be more pleasant places to watch baseball, even if some historical patina is lost forever. Yankee Stadium as I wrote before “will, like the old one, remain a building on the street hugging the elevated subway. Not a stadium machine, like so many others. Glimpses of the field will still be possible from the windows of the passing trains, and a replica of the famous frieze will wrap around the upper deck.”

Both stadiums follow the fashion of retro ballparks inspired by Camden Yards in Baltimore, and replicated in various forms numerous times since. Yankee Stadium echoes itself–or rather its original self–before renovation. It relates to the neighborhood around it, and will, I think wear well in the Bronx.

The Mets new stadium in Queens, named CitiField after the barely breathing mega bank relates to the distant memory of Ebbet’s Field, which of course was in Brooklyn, not Queens. It replaces a mostly unloved stadium that had little charm or comfort. It was, however, a very streamlined structure reflecting its time period compared with the new/old rather fussy architecture of Citifield.

CitiField rendering, Queens

Ebbet’s Field, Brooklyn

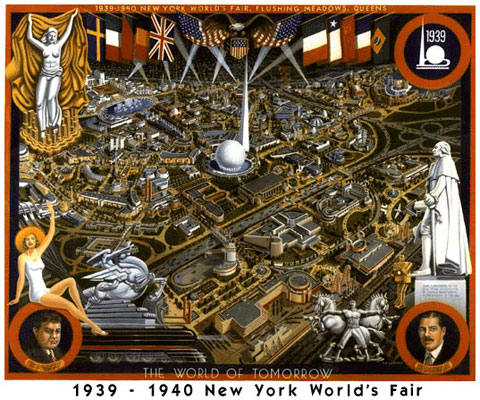

Ebbet’s Field stood in the midst of a tightly knit urban neighborhood while the new reincarnation of it stands in the same vacant parking lot that Shea Stadium used to occupy. Wrong history, wrong location. The real history here is the still vivid memory of two world fairs with their visions of modernity and utopian urbanism. Imagine a stadium design that played to those memories rather than a neighborhood in Flatbush, Brooklyn.

1964 World’s Fair with Shea Stadium at rear

Alas, the new ballpark evokes only fictitious history, though it will undoubtedly be a nice place to see a game. But it’s another lost opportunity for architecture in New York City.

New York/AIG

AIG headquarters in lower Manhattan

The New York Times:

The company paid the bonuses, including more than $1 million each to 73 people, to almost all of the employees in the financial products unit responsible for creating the exotic derivatives that caused A.I.G.’s near collapse and started the government rescue to avoid a global financial crisis.

The AIG building, originally, known as 70 Pine Street or the Cities Service Building, is one of the great Deco period skyscrapers, and still one of the tallest in the city.

New York/Prince Street

New York/Morning Walk

Houston and Mulberry Street — © Brian Rose

Most mornings I walk across town from my son’s school in the West Village to my office apartment just off the Bowery. I’ve been watching the construction of the apartment building above for quite some time. It’s almost finished, another new building entering the market at this particularly uncertain time. The architects are SHoP, one of the most innovative New York firms.

The Puck Building, Mulberry Street facade — © Brian Rose

Houston and Mulberry Street — © Brian Rose

It’s right across the street from the richly detailed brick of the Puck Building with its gold statue of Puck, “that shrewd and knavish sprite” from Shakespeare. My understanding is that the prefabricated brick panels used by SHoP were used to meet contextual zoning requirements. Brick vs. brick. Anyone who has walked along Houston Street in the immediate area knows–the Puck Building’s glory not withstanding–that anything goes here.

Houston and Mulberry Street — © Brian Rose

Houston and Lafayette Street — © Brian Rose

Despite the undulating facade, SHoP’s building feels somewhat reserved in this cacophonous context. But a bit of dignity, with a sly wink, might be the best policy with Puck himself looking on from across the street.