Joel Sternfeld exhibition at Luhring Augustine, New York (digital)

© Brian Rose

A month ago I took in Joel Sternfeld’s exhibit at Luhring Augustine in Chelsea. The work shown—the Oxbow Archive—is a series of pictures of a square mile of farm, field, and woodland, along the Connecticut River, made over a year’s time, ordered by date. The full set of 77 photographs is available in a book of the same name.

View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts,

after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow, 1836, Thomas Cole,

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The landscape depicted in Sternfeld’s series was famously painted by Thomas Cole in 1836 in all the idealized grandeur of the Hudson River School. Sternfeld, rather than mount the nearby heights like Cole, stays close to the muddy ground.

August_19_2006 • Joel Sternfeld • The Oxbow Archive

It is a landscape held, for the moment, in a cautious equilibrium. Tractors leave their imprints in the soft soil among the swaying cornfields. Weeds and puddles of water luxuriate beneath changing skies, as often dull and clouded as sunny and radiant. The fields alternate between cultivated and fallow.

As in Sternfeld’s earlier pictures of the High Line in New York City, the persistence of nature springs forth everywhere despite the taming influence of the plow and other man made incursions. The smallest gestures of tangled growth are carefully described by the view camera—even celebrated. Visual events are carefully, but gently, noted in passing: a flock of sleeping geese in a field, a curled up raccoon (dead or alive?), an abandoned campfire, a toppled tree, clumps of withered cornstalks in a field.

There is no text in the book, though there is a gallery press release that emphasizes the political and social critique offered by Sternfeld’s work, especially in relation to his earlier visual essays on American utopian communities and global warming. These new images fit within the continuity of Sternfeld’s work going back to the more acerbic and ironic pictures of American Prospects. But there is something about these images that resonates on a different level–something personal or spiritual–expressing the culmination (at this stage) of a long career of looking and thinking deeply about the world we live in.

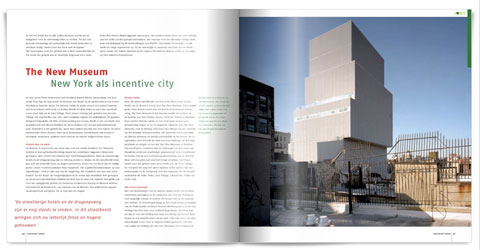

Mohonk Mountain House • New Paltz, New York (digital)

© Brian Rose

Recently, I traveled with my family up the Hudson River to the Mohonk Mountain House with its fairy tale hotel nestled in the mountains near New Paltz. And I thought about Sternfeld’s photographs as I hiked around and climbed Sky Top for the views of the surrounding countryside. The resort dates back to the 19th century and its siting in the landscape arrayed with rustic pavilions and rocky pathways embodies the romantic concept of nature expressed by Thomas Cole and his compatriots. Some of the same ideas can be found in Olmsted and Vaux’s great urban parks and private gardens. Nature majestic, yet tamed by man–if not by actually constructing upon the land, then by framing it, aestheticizing it.

Romantic Landscape with Ruined Tower, Thomas Cole, 1832-36

Albany Institute of History and Art

Smiley Memorial Tower, Mohonk Mountain House (digital)

© Brian Rose

Rustic tower on the promontory of Sky Top overlooking the surrounding Hudson River valley and Shawangunk Mountains.

The Barn Museum at the Mohonk Mountain House (digital)

© Brian Rose

Mountains framed by rocks and trees. Nature sublime, but ordered.

November 29, 2006 • Joel Sternfeld • The Oxbow Archive

For many years photographers embraced the notion of framing the landscape for heroic or picturesque affect. But it has been a long time since serious photographers have taken that approach. Sternfeld doesn’t bring a wholly new way of seeing to the task of photographing the Oxbow. He builds his visual case methodically, image by image, day by day, season by season. He treads the same ground over and over, follows the same paths repeatedly, revisits familiar fields, ponds, glades, the same briar patches. Systematic becomes meditative and vice versa. What emerges eventually is a comprehensive experience of time and space.

March 13, 2006 • Joel Sternfeld • The Oxbow Archive

When I first looked at Sternfeld’s Oxbow images, their stillness seemed absolute. But out of that silence I began to hear sounds off camera–the crunch of the photographers boots on crusted snow, the snap and crack of twigs and branches, the sibilance of wind through leaves. And then, the growl of a distant tractor, the drone of an approaching plane, the white noise of nearby Interstate 91. I began to sense the encroaching proximity of civilization in these unpeopled images.

When I greeted Joel Sternfeld at the exhibit opening back in September I told him that these were, perhaps, his most beautiful photographs. His response was that he felt that he was born to do this work. Whatever the presumed message of this project, environmental or political, I see the Oxbow Archive, ultimately, as a search for an ineffable nexus–a muddy path leading into an unknowable and uncertain future.