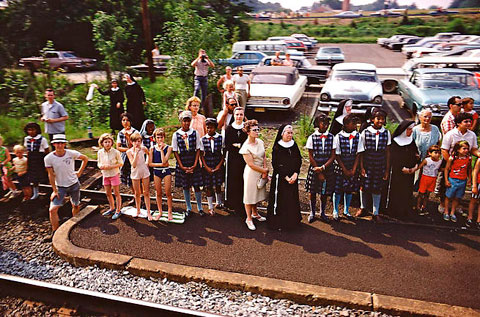

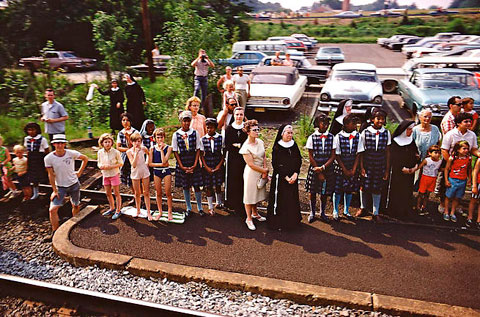

Paul Fusco, RFK funeral train, 1968

I was 14 years old in 1968, undoubtedly the most tumultuous year since World War II–at least in the western world. Although I was too young to be seriously engaged in what was going on, I was acutely aware of the epic events occurring–Vietnam, civil rights, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, and the violent end to Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia.

Two exhibits I visited recently in New York touch on events of 1968: Paul Fusco at Danziger Projects (show closed October 4) and Josef Koudelka at Aperture. Fusco photographed Robert Kennedy’s viewers of the funeral train as it made its way from New York to Washington, D.C.

I remember well watching the railroad cortege on television as it passed the thousands of people who lined the tracks. I also have a distinct memory of a brief bit of video shown once, in which a train coming from the opposite direction mowed down a number of people standing on the tracks adjacent to the funeral train.

Paul Fusco, RFK funeral train, 1968

When I first saw the Fusco pictures, I was immediately swept back to the sorrow and apprehension of that time, to the fear and uncertainty that I have never been able to shake, a fear that rises to the surface today as a black man carrying the hope embodied in the Kennedy brothers nears the presidency, as earthshaking economic events rumble around us.

Fusco’s photographs were very simply made. On assignment from Look magazine, he rode the funeral train and did what he could from a fixed vantage point. He aimed his camera at the crowds and small knots of people standing at relaxed attention, some waving, some saluting, troubled, saddened faces, staring, transfixed, as the rail coaches slid by.

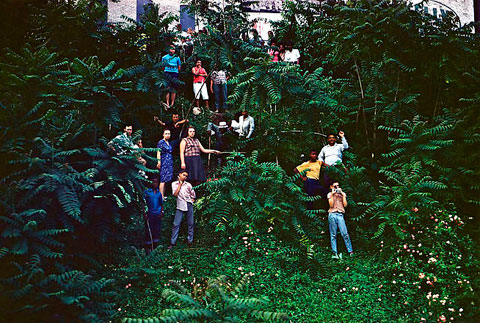

Paul Fusco, RFK funeral train, 1968

Fusco made his photos on 35mm Kodachrome, a vibrant slide film that stands up well over time unlike early color negative film, which tends to shift color and fade. As a result, these images from 40 years ago seem fresh and immediate, which makes them emotionally all the more jarring. The people depicted came “as-they-were” in a colorful array of flowered prints and decidedly unfunereal stripes and plaids. It was June and people came in shorts, bathing suits, sandals and bare feet. And although it was 1968, one sees scant evidence of the psychedelic trappings that so dominate our collective memory of the era.

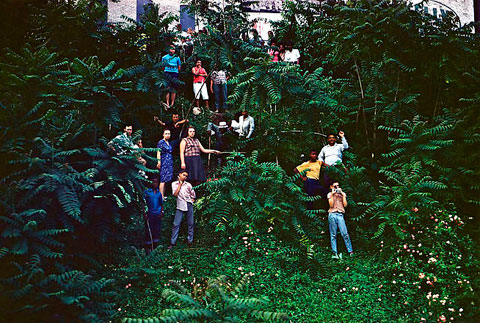

The train passed through rural areas, small cities like Trenton, and big ones like Philadelphia and Baltimore where the faces are mostly black, people standing in scruffy backyards and vacant areas along the tracks. Some of these neighborhoods were in the midst of violent upheaval as racial frustrations boiled over after the murder of Martin Luther King. Fusco’s pictures, while freezing the momentary unity of grief, also reveal the racially segregated nature of a society coming apart at the seams.

Paul Fusco, RFK funeral train, 1968

Because the train remained in motion, most of Fusco’s photographs were necessarily made on the fly. They are fleeting glimpses, poignant, abbreviated moments of individual solitude among crowds. Fusco focused on the motionless people, rotating his head and camera slightly to stay fixed on his subjects, as the train moved horizontally. The blurring of the surrounding landscape further isolates the figures and creates a model-like hyper-reality, akin to recent narrow focus imagery created in Photoshop.

The images have a posed quality as well, due to the fact that people had staked out viewing positions, sometimes awkwardly balancing on steep embankments or even standing on elevated objects. As the train went by they looked intently at the coaches and often their eyes met the gaze of the photographer. In Fusco’s photographs this relationship creates a strange and compelling phenomenon–they seem to look at us as we look at them. Do we recognize ourselves?

***

Paul Fusco’s photographs have been collected in a handsome book, RFK, published by Aperture. It tries to be both a tribute to Bobby Kennedy and an art photo book, which I think is a little forced. The book starts with pictures not taken from the train of the memorial service held in St. Patrick’s Cathedral and ends with the funeral in Washington. I would be happier without these bookends.

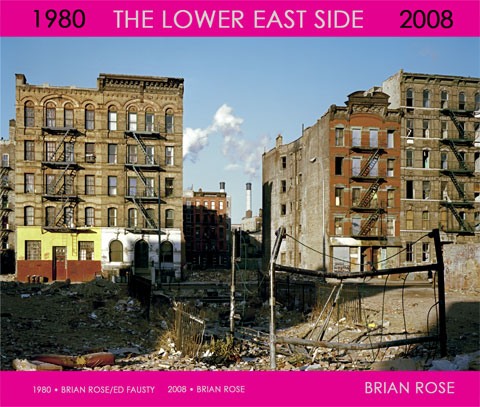

Paul Fusco at Danziger Projects • Brendan, my son, at left (digital)

The images as printed in the book, however, are nicer than the gallery prints, which are somewhat harsh and over saturated. The slightly more muted tones in the book seem more natural to me. Kodachrome is a punchy color material, but I don’t think prints have to mimic the straight slide film.

Next, a look at the Koudelka exhibit.