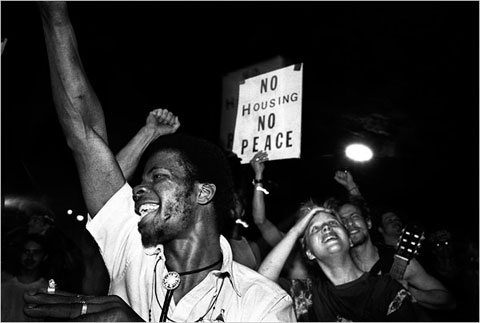

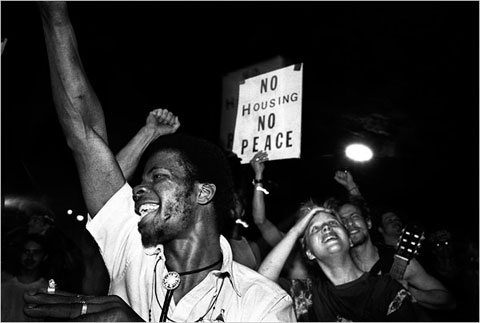

East Village protest, 1989, Q. Sakamaki

I have to admit being astonished to see the New York Times run no fewer than eight photographs from Q. Sakamaki’s new book “Tompkins Square Park.” This is a book about the tumultuous period during the late ’80s and early ’90s in the East Village. The black and white pictures of the showdown between squatters and activists on one side and the police on the other strike me as classic examples of what so often goes wrong with photo journalism. We as viewers are thrust into the action–whether protests, violent confrontations, or rock concerts–but are given little breathing room for a more considered view of things. History becomes rendered as a series of spasmodic incidents, character types, and visual clichés.

It’s not that the things seen in Sakamaki’s photos didn’t happen, it’s that they happened to different people in different ways. The photographs and accompanying polemic do not offer the possibility of differing experiences of the same time and place.

***

Tompkins Square basketball courts, cold winter day, 1980

© Rose/Fausty (4×5 film)

I was a frequent user of the park in those days, playing basketball on the courts at the corner of Avenue B and 10th Street. We were a ragtag bunch of ex-high school stars, ex-college players, and even a few guys who played pro overseas. The basketball could be amazingly good at times, but ultimately nobody was tall enough, fast enough, or strong enough to escape life on the courts of Avenue B.

The players were black and latino, many from the projects nearby, with a few white guys like me thrown in. And there was the incomparable Joe Ski, his last name shortened, I think, from an unpronounceable Polish appellation. Joe had the best jump shot I’ve ever seen. Not so much because his form was mechanically perfect, but because when any game was on the line, Joe would bury the winning shot. I guarded him a lot–we were both about 6’4″–and I gave him everything I had defensively. Joe’s favorite ploy was to draw me right into his jump shot–I’d go up in the air hanging all over him 20 feet from the bucket–he barely able to glimpse the rim–and somehow, miraculously, he would bang the damn thing in and walk off the court like it was the most routine thing in the world.

There was another guy who hung out in the park in those days–his name has vanished from my brain–and he loved to watch us play basketball. I had no idea where he lived, what he did, how he survived, but I knew he wrote poetry, and he also loved to talk politics. One day we heard that our poet fan had died–of natural causes I believe–and a memorial was held on the following Saturday on the basketball court. So, we all stood there, a motley crew if there ever was one ranging from school dropouts from the projects to college grads like me. A friend read one of his poems, a starkly honest portrait of Joe Ski–a white man in a black man’s sport, too slow, not tall enough–but as magnificent a player as you’d ever see.

The basketball players were mostly disdainful of the white anarchist types who inhabited Tompkins Square Park during the late ’80s. These were guys who grew up poor, worked hard, and in some cases, had just escaped becoming another Lower East Side statistic. Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s the park was often desolate, like much of the neighborhood around it. The squatters came later, after a lot of political activism had already secured buildings and gardens for the community–despite losing many battles–and acted like their cause was the only cause that mattered.

***

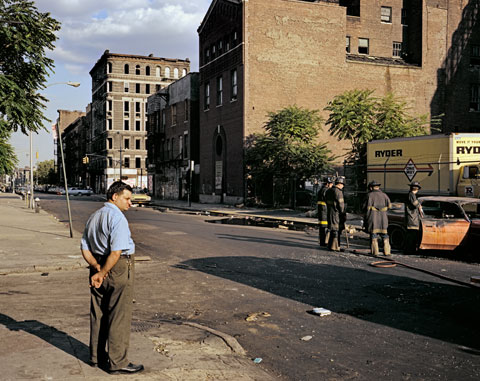

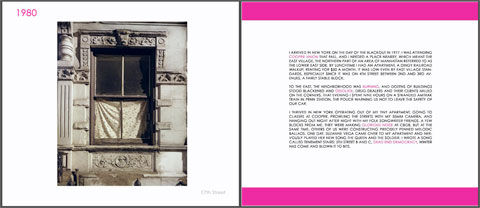

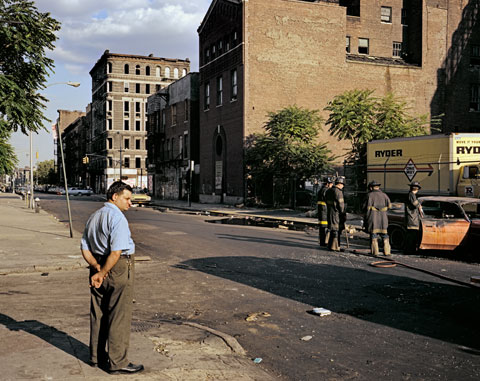

E1st Street with the Cube Building in rear, 1980

© Rose/Fausty (4×5 film)

1988, the same year as the Tompkins Square riots, I was involved in a hard fought battle to save an abandoned building on the corner of Second Avenue and E1st Street. The city had proposed selling the Cube Building, as it was known, for a dollar to a private developer. As a member of the Cooper Square Committee, a housing advocacy group, I led the effort to get city approval and state funding to rehabilitate the building for 22 formerly homeless families. It was just one project on the Lower East Side–a drop in the bucket, perhaps–but for me a concrete triumph against the forces that others ranted, often impotently, about.

We essentially suckered New York state into the deal claiming that it would cost about a million dollars to renovate the building, even though we knew it would likely take more. It ended up over 2 million dollars. But the state was eager, if not desperate, to give out funds earmarked for alleviating the mounting homeless problem, and we had a project ready to go.

I remember well the critical moment when we met with state officials in the World Trade Center for final approval of our plans, such as they were. I was both terrified and sick with stomach flu at the meeting, which ended with state commitment to fund the project. Afterwards, I rushed home in a cab, feeling elated but increasingly ill, ordered the driver to stop, jumped out and collapsed on the street, throwing up on the Bowery at Houston Street, looking like just another of the hundreds of derelicts who inhabited the area at that time.

***

Tompkins Square Park, jazz festival, 2007

© Brian Rose (4×5 film)

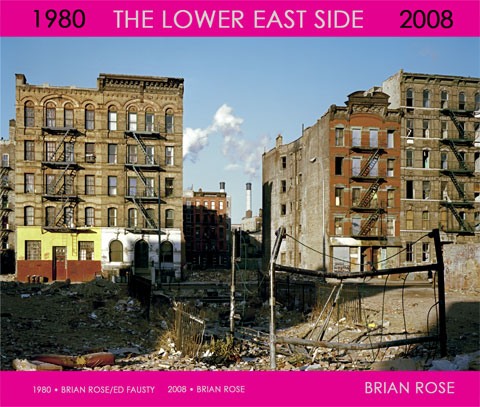

So, I cringe when I read this in the Times:

“This book focuses on Tompkins Square Park as the symbol and stronghold of the anti-gentrification movement, the scene of one of the most important political and avant-garde movements in New York history,” Mr. Sakamaki writes in an introduction.

There was no single overarching political and avant-garde movement in New York at that time. There were a great many different conflicting initiatives and struggles–there were wins and losses–and in the end, the wave of gentrification that swept over the East Village and the Lower East Side, especially after 9/11, was the result of far reaching forces extending beyond the microcosm of Tompkins Square Park that have transformed the whole city.