Depth of Field: Modern Photography at the Metropolitan

Lots of milling about and reading explanatory labels.

I went to the Metropolitan Museum yesterday to check out two photography exhibits that have been up for a while. The most prominent of the two–at least in terms of publicity and location–is Depth of Field: Modern Photography at the Metropolitan, which occupies a new gallery dedicated to contemporary photography. As is usual of group shows, it is primarily about photography, as opposed to a show of photography. Above all, it is a curators show, a staking out of turf, a doctoral thesis, if you will, that the rest of us, perhaps, shouldn’t have to be subjected to.

Pixellated World Trade Center image by Thomas Ruff

The exhibition introductory text lays out the tired–for me anyway–premise that the past 40 years have been chiefly about experimentation, the breaking down of boundaries, and the blurring of “the line between reality and the imagination.” And naturally, that digitalization has rendered analog photography almost obsolete. The lineup of artists/photographers offered as evidence of all this is largely comprised of the same names one encounters over and over in commercial galleries and other museums. (Bechers, Sherman, Ruff, Struth, Gursky, Dijkstra, etc.)

There are also a number of artists included who only use photography tangentially like Dennis Oppenheim and Gordon Matta-Clark, which is obviously supposed to make a point about photography’s extended reach into conceptual, performance, and installation art. Not a particularly novel idea. I appreciate, more, how Adam Fuss’s large photogram evokes the most basic elements of photography, light and shadow.

Granted there are some nice images in the show–though few that I haven’t seen elsewhere–and many of the photographers deserve the attention they’ve gotten, but… I guess I’m exhausted of having “the old new” shoved down my throat, and I’m yearning for a fresher perspective on where we are, or might be going.

Untitled, Sharon Lockhart

Rodney Graham’s upside down tree seen right side up in the display case reflection.

Intro text:

The hallucinatory clarity of Rodney Graham’s upside-down tree, Sharon Lockhart’s reflection-filled hotel room, and Uta Barth’s luminous river view are all, nevertheless, rooted in an exploration of analog photography’s unique technical and material underpinnings, pushed to the point of a bedazzled transcendence.

Okay. Maybe. Analog is all right as long as it’s transcendent. I left the gallery and began looking for the Lee Friedlander exhibition that I knew was nearby. I saw that the main photo/print galleries were closed for a show change, so I wandered out into the European sculpture gallery filed with Rodins and the like, and still I couldn’t find Friedlander. Finally, I came across a little sign pointing toward a doorway with the word “Photographs” printed on it. Ah, this must be the place.

Friedlander must be around here somwhere.

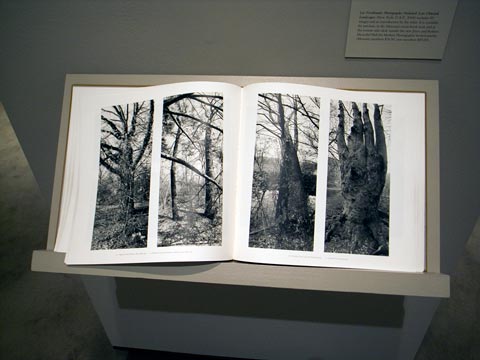

Inside was Lee Friedlander: A Ramble in Olmsted Parks, the result of many years of his project photographing the landscapes of Frederick Law Olmsted. Let me say right up front, as someone who has spent a lot of time photographing in Central Park and Prospect Park–both Olmsted masterpieces–that Friedlander’s photographs have little to do with Olmsted or the particular design aspects of these landscapes. These pictures are visual journeys into the strange and unfamiliar, or to borrow from John MacPhee, into “suspect terrain.”

Sparsely visited “hidden” gallery.

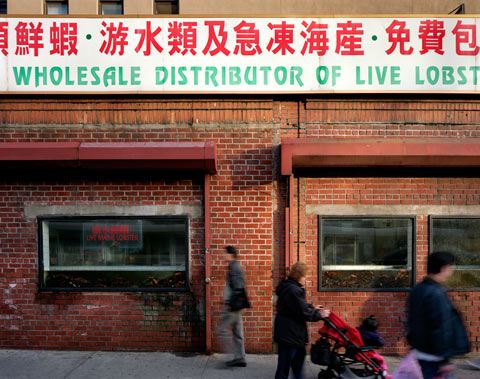

As is well known, Friedlander’s early work dealt with the social landscape, street photography, and the bric-a-brac of pop culture all around us. He was in love with advertising signs, crazy juxtapositions, objects near and far, reflections, the great jumble of stuff in the world all held together by a spider’s web of compositional tension. Sometimes his work encompassed social criticism as in his pictures of factory workers, a disturbing series of photographs of humanity at the mercy of machinery and the drudgery of manual labor.

Later, when Friedlander turned to the natural landscape, albeit man-made landscape, he began to explore the idea of making photographs emptied of the cultural touchstones integral to his earlier work. These pictures rather than losing their power probe deeply into the visual wilderness of pure imagery. Friedlander consciously sought out this wilderness in the semi-civilized landscape of Olmsted. I know from my own experience that Olmsted’s landscapes, while natural in appearance, are highly ordered compositions with carefully framed vistas and hierarchical progressions through space. Friedlander is not really interested in these aspects of Olmsted. He uses Olmsted’s order for his own purposes.

Friedlander trees.

These photographs, as I read them, push the act of making pictures into uncharted territory, both terrible and beautiful. Trees loom as anthropomorphic beings throwing apples at Dorothy on the Yellow Brick Road. Shadows splay over layer upon layer of bare branches obscuring any way of escape. A complex rippling and dappling of sunlight projected onto leaves and stones obliterates recognition. Throughout these pictures Friedlander utilizes the compositional devices of his older work, but even though the moves are familiar, I find myself led into a disorienting world, shimmering with light, where boulders and trees are made ephemeral, and Olmsted’s ordered space is shattered.

Call it “bedazzled transcendence.”