All over town there are posters for the movie Cloverfield depicting a ruined lower Manhattan. For those of living downtown (or anywhere?) the images are chilling reminders of what happened in 2001. Is making a movie like this shameless exploitation? Yes. Should one avoid seeing it? Yes.

New York/Grand Central

New York/Bowery

East 1st Street/Bowery/Houston Street

I’m working on a series of pictures of the Bowery taken over the past few years as an adjunct to my Lower East Side project. The picture above was taken during the demolition of the AvalonBay development site bounded by the East 1st Street, The Bowery, and Houston Street.

The single building standing is 295 Bowery, infamous as the location of McGurk’s Suicide Hall, where a number of prostitutes were said to have ended their lives by swallowing acid. That was in the late 1890s long before the street had reached its most desolate nadir as skid row. The history of the building is nicely told by Rob Hill on his website.

In its last days, artists, most notably feminist author and artist Kate Millet lived there. She and others were relocated to make way for approximately 600 apartments built on both sides of Houston Street–very expensive rentals–with 20 percent of the units reserved for low income residents. Newcomers to the neighborhood are mostly unaware that the redevelopment of this site was part of a deal made with the community to rehabilitate and preserve another 600 units of low cost tenement housing on several adjacent blocks.

New York/Lower East Side

The Bowery Mission and New Museum

Yesterday, the temperature soared into the 60s, so I took the opportunity to do more Lower East Side pictures. I left my apartment/office on Stanton Street and began walking down the Bowery stopping to do a photograph of the Bowery Mission adjacent to the New Museum. There are few facilities ministering to the homeless and addicted left in the neighborhood, but this is one of the oldest, and it continues to provide meals and other services even as the flophouses and bars have vanished.

The Bowery and Hester Street

I walked through the lighting district to the south of Delancey/Kenmare Street. There used to be many such unofficial markets in Manhattan–the flower district in the West 20s, the radio district obliterated by the World Trade Center, the restaurant supply area of the Bowery hanging by a thread–but gradually they’ve been dispersed at a loss to the diversity of the city. At Grand Street, the Bowery has been subsumed into the ever expanding Chinatown, which has grown north and east further into the Lower East Side. On the corner of Hester a large site has been cleared for new construction, a tacky glass tower pictured on a sign on the construction fence. I did a series of shots here with the 4×5 camera.

Eldridge Street Synogogue

I then walked east on Hester and then downtown on Eldridge to the Eldridge Street Synogogue that I visited a few weeks ago. The late 19th century structure has been restored and functions now in part as a museum. It is surrounded by the visual cacophany of Chinatown, a scene I’ve been trying, with mixed success, to get into a photograph. Today, I tried again, timing my arrival for the low winter sun raking just above the nearby Manhattan Bridge. I got up on a rather high stoop of a tenement opposite the synagogue and did two wide views of the synogogue showing adjacent buildings. I also did a photograph looking north through layers of signs with Chinese lettering.

Eldridge Street

A tourist came by holding a Time Out guide gazing up at the building. As we chatted, it struck me how much this scene was an echo of the old Lower East Side when people jammed the streets and sidewalks, commerce of every description was carried out in the open, and when there was a density of sights, noises and smells that filled the senses.

East Broadway and Pike Street

I walked around several blocks in this area photographing various storefronts as the light began to fade. At Canal and Eldridge a large 19th century building was being demolished–another development site.

The project continues. Today I sent out 200 postcards to galleries, museums, and individuals. Book? Exhibit? Website for now.

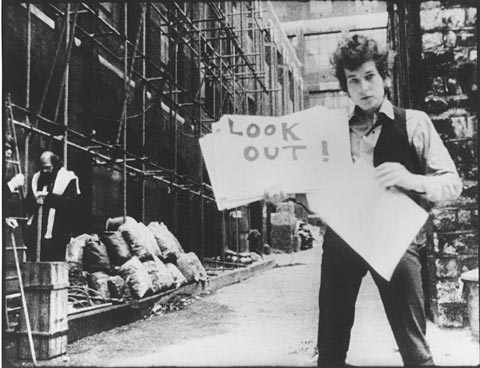

New York/I’m Not There

On Saturday I finally got to see I’m Not There, the non-documentary film circumscribing the figure of Bob Dylan by Todd Haynes. It’s a stunning movie, one that explores the myths, clichés, and even lies that form the persona of the man born as Robert Zimmerman. Six actors play different aspects, or different periods, of Dylan’s life, including an 11 year old black boy as Dylan’s Woody Guthrie doppelgänger, and Cate Blanchett as the acerbic Don’t Look Back Dylan.

Don’t Look Back, Allen Ginsburg in background

The latter, of course, refers to the ground breaking direct cinema film by D.A. Pennebaker (who was a teacher of mine at Cooper Union). Pennebaker’s masterpiece, while presumably a fly on the wall peek at Dylan on the road, probably furthers the mythology of Bob Dylan more than any other film. It’s a knowing collaboration between two ambitious artists, each with a profound understanding of the power of the camera to document and manipulate.

Cate Blanchett on screen in Film Forum

All of the six visions of Dylan are effective, but Cate Blanchett’s performance as the wild-haired skinny-legged black and white Dylan of the mid-sixties is amazing and has to be seen to be believed. Her sly smiling gaze at the camera as the film ends, is brilliant—Dylan, as the ultimate joker, however much he may have been victimized by celebrity, the press, and the insatiable blood lust of his fans. There’s lots of humor in I’m Not There, despite the art film gravity—Dylan and the mop-topped Beatles rolling down a hill, and Allen Ginsburg (another great joker) riding alongside Dylan’s limo. The obvious reference is to the wonderful Beatles mock documentary A Hard Day’s Night, while Ginsburg, way back then, made a cameo appearance in Don’t Look Back.

Although Haynes is dealing with an American icon through and through, I’m Not There is a film suffused with the spirit of the French New Wave, particularly Jean Luc Godard’s Masculin Feminin another film that veers between a verité style and a deconstruction of the conceits of cinematic storytelling. There are also Felliniesque moments with costumes and freaks, and the outlaw segment with Richard Gere is all McCabe & Mrs. Miller, the early Robert Altman film. The references go on and on, and the the bones of the film will undoubtedly be picked clean by film buffs and Dylanologists.

Walking through Soho after the film. Numerous scenes in the film

were set in the streets near Film Forum in Greenwich Village.

The one persona, however, that’s not there in I’m Not There, is the latest incarnation of Bob Dylan, the grizzled veteran whose last few albums have plumbed the depths of American music with songs as strange and enigmatic as those from his Basement Tapes era. The story is not over as Dylan writes—songs and memoirs—and continues to tour and tour as if there’s nothing else left to do. It may not be Woody Guthrie’s hobo boxcar that Dylan rides from town to town, but its a long train curling into the night, nevertheless.

New York/New Year

My family has survived its first year together in New York. For the past 15 years I’ve been traveling back and forth between here and Amsterdam, but for my wife and son, this was a new, and potentially challenging experience. Brendan has thrived at PS 3, the elementary school in the West Village, and Renée has worked a half year for Community Board 4, one of the citizen advisory bodies involved in the official decision making process for the city. CB 4 covers Hell’s Kitchen (west Midtown) and Chelsea where many important urban projects are in the works–the Highline, the west side rail yards, and the rebuilding of Penn Station to name a few.

We look forward to new adventures this year, photographic and otherwise, and I plan to keep this blog going through it all. Thanks to all who have been following it.

New York/New Museum

The Museum (Hell Yes! – Ugo Rondinone)

The installation encapsulates the philosophy of openness, fearlessness, and optimism that surrounds the New Museum’s reemergence in the contemporary art community, as well as its history as the home of socially committed contemporary art. — The New Museum website

I finally got to the New Museum the other day braving the holiday crowd that has pressed into this out of whack wedding cake of a building since it opened a month ago. I’ve already written about the exterior architecture, which fits admirably into the polyglot of the Bowery. If there’s ever a place where anything goes, this is it.

Inside, the building is less arresting, somewhat sober, a series of white containers for art. The offset setbacks of the exterior allow for unobtrusive skylights, which supplement fluorescent tube lighting. I’ve never cared for this kind of “European lighting”–you see it lots of galleries over there–but it works fine for the sculptural pieces in the opening exhibition “Unmonumental.” For most wall art I prefer spots.

The New Museum

No photography in the galleries, so we’ll settle for a restroom view.

The New Museum has none of the luxe quality of the Museum of Modern Art, and I have no problem with that. The architects’ make only a few signature gestures, most notably the narrow stairs linking three floors of galleries. It’s just wide enough for two people to pass going up and down, and it reminded me how the old Modern once featured a human scale staircase as an important element of circulation. (I think it’s still there, actually, lost in the hustle and bustle and endless escalators.)

Museum of Modern Art, photo via CitySpecific

I was pleasantly surprised to see a rather accessible and generous opening exhibition at the New Museum. Surprised, because so much art these days is coded for the smug acknowledgment of the select few or panders to the titillation of the semi-sophisticated. Unmonumental is the apt title of the exhibit, which can be loosely described as assemblage art, three-dimensional constructions often made from disposable bric-a-brac. It’s a sculpture show.

I won’t go into the specific pieces–not as long as picture taking is forbidden in the galleries–but I found much of it freshly energetic, clever without being off putting, and just a lot of fun to rummage through. There were too many people in the museum for a leisurely visit, and we’ll see if the crowds continue after the first of the year.

The Sunshine Hotel adjacent the New Museum

One of the last Bowery flophouses

I went when I did because they were screening a documentary about the Bowery, where the museum is located, and which forms the western periphery of my Lower East Side project. The film presented the history of the street from its days as the road to Peter Stuyvesant’s farm to a last stop skid row. Except for a few hangers on in places like the Sunshine Hotel, there are no more Bowery bums.

New York/Hudson Street

New York/LES

East 1st Street, The Bowery and Second Avenue, 1980 (4×5 film)

In the post below I ranted a little about the supposed death of photography (Is Photography Dead/Newsweek) caused, in part, by Photoshop, a program so amazing that one no longer needs the temporal world to make images. Anyway, back in 1980 when photography was, presumably, still alive I began making pictures of the Lower East Side in collaboration with Ed Fausty using a 4×5 view camera. You can click on the link at the top right to see the whole thing.

We were doing the project by the skin of our teeth financially, and rarely checked exposures with expensive Polaroids. So, some of the negatives are a little thin (underexposed), making them difficult to print. And some of them were not developed properly, and have problematic color shifts. The picture above was one of those, both thin and color shifted. Add to that the degradation of the film over the years, due to the instability of the materials from of that era, and you have a near impossible situation.

But thanks to Photoshop it is possible to coax the color back and largely correct the color imbalances–bring dead pictures back to life, as it were. It’s not a pushbutton process, however, takes a lot of time, and requires a good deal of experience with the many different ways to select areas, colors, and densities. The end result, in this case, is an image never printed before, that comes alive in the present.

The Lower East Side project spans 28 years of time, and is about looking back, reinterpreting, and looking again in the present. In that sense the work is not primarily about static visual documents, but rather a process that takes into account the actions of time and change. Understanding the notion, that images of the “real world” are constantly acted upon by the shifting sands of culture, opinion, and history, is critical to working with these factoids called photographs. Nevertheless, one does not necessarily give up on the enterprise of “taking pictures” because their veracity can be questioned.

Peter Plagens in his Newsweek article refers at one point to “photography’s tango with the truth.” I think that’s an apt description, and it encapsulates the power of photography not its weakness. As a photographer I may play the part of Joe Friday in search of hard evidence. “Just the facts, ma’am.” But it’s the tango with the truth that holds our interest and keeps the game alive.

New York/Death of Photography

Tangier Island, Chesapeake Bay, Virginia, 1984 (4×5 film)

Is Photography Dead? Peter Plagens in a Newsweek article makes a mess of the recent explosion of photography in the museum/gallery scene and the concomitant use of Photoshop to create seamless fictional realities.

Here’s the key paragraph from his article:

Yet wandering the galleries of these two shows (the Met and National Gallery), you can’t help but wonder if the entire medium hasn’t fractured itself beyond all recognition. Sculpture did the same thing a while back, so that now “sculpture” can indicate a hole in the ground as readily as a bronze statue. Digitalization has made much of art photography’s vast variety possible. But it’s also a major reason that, 25 years after the technology exploded what photography could do and be, the medium seems to have lost its soul. Film photography’s artistic cachet was always that no matter how much darkroom fiddling someone added to a photograph, the picture was, at its core, a record of something real that occurred in front of the camera. A digital photograph, on the other hand, can be a Photoshop fairy tale, containing only a tiny trace of a small fragment of reality. By now, we’ve witnessed all the magical morphing and seen all the clever tricks that have turned so many photographers—formerly bearers of truth—into conjurers of fiction. It’s hard to say “gee whiz” anymore.

First of all, there have always been photographers who used the medium to create alternate realities, or who sought to make photography more art-like by using different techniques, materials, or color palettes, and, of course, those who mixed media to create hybrid objects that were not easily classifiable. Indeed, it has long been understood that photography’s relationship with reality, while rooted in it, is tenuous. Even a photographer like Cartier-Bresson considered himself, ultimately, a surrealist despite being the epitome of a “straight photographer.” As the Richard Lacayo wrote in Time earlier this year:

We connect Cartier-Bresson to photojournalism because he founded the news photo agency Magnum. But he was trained first as a painter. And when he started to take pictures in the early 1930s he wasn’t interested in gathering news. He was a newly hatched surrealist on the hunt for miracles, moments when the real world somehow gave you a fleeting glimpse of the uncanny.

I recall the John Szarkowski curated show at the Modern in 1978 (just after I arrived in New York) called Mirrors and Windows, which posited two main paths in photography, the one seeing out into the world through a frame, the other reflecting the inner world of the photographer. This dialectic made for a contentious exhibition–which side of the great divide do you live on? Obviously, there was and is no clear divide between inside and outside, although there is no doubt that photographers and artist have different intentions with regard to depicting the inner and outer world. Those intentions are still at the heart of the matter, and the introduction of Photoshop has not changed things one bit.

Robert Hughes, back then, wrote in Time about Mirrors and Windows:

The most striking thing illustrated by the show is how far behind photography—meaning the photographs Szarkowski designates as “serious”—has left its old role as witness to public events. …Wars, elections, riots, disasters, communal ecstasies, the speeches of politicians and their deaths—all are eaten up by the omnivorous lens, as photography (through journalism) defines the terms of our fictitious intimacy with the world.

So in 1978 Hughes talked about photography and the “fictitious intimacy” with the world, and now almost 30 years later Plagens refers to photographers as former bearers of truth turned into “conjurers of fiction.” Plagens goes on to suggest that the turning point in this move away from realism was the work of Cindy Sherman, specifically her movie stills series, which quoted a photographic genre expressive of verisimilitude as opposed to unmediated reality. As actual photographs, however, they are documents of a performance–her dressing up and posing in carefully chosen locales–and have nothing to do with a Photoshop created reality. While they were groundbreaking pictures conceptually, they were, otherwise, conventionally made.

Tangier Island, the Chesapeake Bay, Virginia, 1984 (4×5 film)

For a while it appeared that postmodernism, which Cindy Sherman is linked with, declared every creative endeavor dead on arrival. How could one write a conventional story, make a painting, or compose music as authentic expressions of observation or self-reflection once we knew that such attempts were exercises in futility like trying to nail jello to a wall?

Well, we stared down that abyss and moved on with a myriad of different strategies (fractured beyond all recognition) in spite of the eschatological pronouncements of the high priests of art criticism. I will have more to say about all this, perhaps, unless the now useless task of making photographs gets in the way. Stay tuned.

New York/Houston Street

New York/New Museum

Here is a wider view of my rooftop looking toward the New Museum made with the 4×5 camera. It was a crisp, but not uncomfortably cold morning. This is the back of the building, although, except for the transparent glass ground floor, there really isn’t a front or back to the tower. But since it only takes up a small lot on the Bowery, it will tend to be viewed primarily from the street.

This is an oblique view that will work well in my Lower East Side series–a roofscape rather than a streetscape. Another icon of the rapidly changing neighborhood.

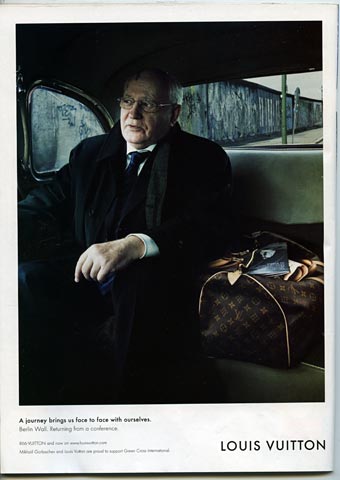

New York/Gorbachev

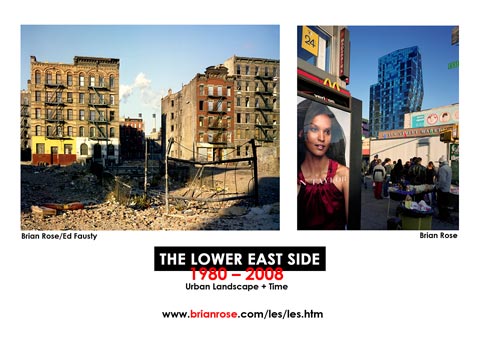

New York/LES

Today I launched my newly redesigned Lower East Side web pages. I’m planning to send out, shortly, the card above. As I worked on the new LES pictures, I realized that I have a surprisingly complete set of images of the Bowery taken in the past five years. This last remaining strip of gritty reality in Lower Manhattan is poised for rapid gentrification, the recent opening of the New Museum a vivid marker of the change. So, I am also putting together a Bowery web page.

Yesterday, I discovered that the popular blog MetaFilter featured my Lost Border website, and since then, I’ve gotten about 1,500 visits–it’s usually 50.

New York/Eldridge Street Synagogue

It snowed on Sunday and for much of the day the city looked quite magical. Brendan, my son, and I walked across town and down the Lower East Side to visit the opening of the newly renovated Eldridge Street Synagogue, which as I understand it, will be called Museum at Eldridge Street. The restoration looked beautiful, a good sized crowd was on hand, and a klezmer band played jauntily in the main sanctuary.

The synagogue is located at the southern end of Eldridge Street near the Manhattan Bridge, an area that is now the heart of Chinatown. The incongruity of the old world Moorish themed building surrounded by Chinese businesses is striking. But this is the kind of jarring cultural collision that makes the Lower East Side and New York in general so fascinating.

New York/New Museum

Calvin Klein ad morphs into New Museum ad on Houston Street

Well, I won’t be going to the New Museum today as planned because they have already given out all the tickets to the 30 hour free admission marathon. The ultimate brilliance of the New Museum may be their ability to harness the full corporate/media juggernaut that runs this town. Will “new” art be mostly about the art establishment creating a new brand? Will the New Museum serve primarily to give museum imprimatur to artists already ensconced in the commercial galleries? For those of us toiling in the shadow of the museum–literally in my case–the museum may represent a shining, but unattainable Oz.

The New Museum from my rooftop

Yesterday morning I climbed out my window and up the fire escape to photograph the New Museum from the roof. It is perhaps the best way to view the building, its off kilter boxes emerging amid the confusion of the elevator sheds, skylights, and water towers that define the rooftop landscape of lower Manhattan.

The New Museum building, designed by Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa of the firm Sanaa, is, on the one hand, a pristine object standing aloof from the still very gritty Bowery. But viewed close up, the metal scrim, which glistens in the sun from a distance, is rather more utilitarian. As I wrote a while back in an earlier post, it has a provisional off-the-shelf feel unlike the richer materiality usually associated with museums. It is, after all, a institution dedicated to the here and now as opposed to the preservation of the past.

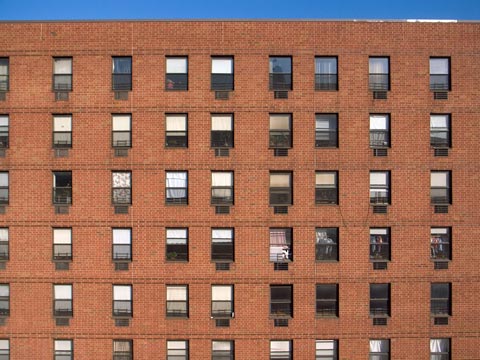

I took a number of pictures with the view camera, a few not including the New Museum. Running the whole block of Stanton between the Bowery and Chrystie is a low income housing project built during the ’80s composed of an endless monotony of brick and windows. This, too, is part of the neighborhood in which the New Museum now calls home.

New York/Hampton Roads

I traveled with my family to Virginia for the Thanksgiving holiday to visit with my parents–separately–as has been necessary since their divorce a long time ago. Extended sit downs with one parent or the other are to be avoided since they usually, unfortunately, turn painful. My mother reminisces about my growing up, remembering things as a parallel universe that barely jibes with my own recollections. My father, who is elderly but not senile, cannot or chooses not to remember anything at all.

The Monitor Center, The Mariner’s Museum, Newport News, Virginia

So, excursions out into the real world are necessary, especially since we are traveling with a nine year old who is not content to sit around the living room. This time we drove down the peninsula (between the James and York rivers) to the Mariner’s Museum in Newport News. I’d only been there once as a child and knew that much had changed in the last few years, most notably the building of the Monitor Center, a new wing of the museum to house the recently recovered turret of the ironclad Civil War ship the Monitor.

The Monitor Center is actually a vast addition to the original museum, perhaps doubling its size, and it tells the story of the famous battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac (dubbed the Virginia by the Confederates). The center includes interior and exterior mock-ups of both ships as well as the actual rotating gun turret of the original ship salvaged from beneath the sea off the Outer Banks of North Carolina.

Monitor memorial, Greenpoint, Brooklyn

Earlier this summer I photographed the Monitor memorial in McGolrick Park in Greenpoint as part of a documentation of Civil War monuments in Brooklyn. Standing before the memorial for the first time I wondered why this rather odd statue was placed here. On it were the words:

STATE OF NEW YORK

TO COMMEMORATE THE BATTLE OF THE

MONTOR AND MERRIMAC

MARCH 9TH 1862

AND IN MEMORY OF THE MEN OF THE MONITOR

AND ITS DESIGNER JOHN ERICSSON

So it goes with a majority of memorials that inhabit, often invisibly, the streets and parks we pass through daily. The event, person, or locale depicted has, with the passing of time, become disconnected from our own era. These, often, lavish tours de force of sculpture serve more as urban furniture than as carriers of memory or history.

The Monitor’s turret

In Hampton Roads, in the heart of Navy country, the battle between the Monitor and Merrimac is central to the region’s symbology and meaning. The Monitor’s turret lies in repose beneath a watery solution (eventually to be exhibited dry) like Lenin embalmed in his tomb in Red Square. The accompanying exhibition is exhaustive in detail, almost fetishistic in its focus on this one story and object.

In New York, however, where the Monitor was built, there are two monuments offering cryptic references to the ship and the battle. One is the strange sculpture in Greenpoint, the other is a statue of Ericsson in Battery Park in Manhattan, which I have undoubtedly walked by, but have so recollection of ever seeing.