Stephen Shore exhibit at ICP

Closing this week at ICP in New York is Biographical Landscape: The Photography of Stephen Shore, 1969-79. If you are in the city in the next few days, don’t pass up the chance. When I first began shooting color in 1976 Shore was well on the way to completing the work that established his career and public personna. As a student I was aware of only several people shooting color with a serious artistic intent: Joel Meyerowitz, William Eggleston, and Stephen Shore. For me, Meyerowitz was a street photographer (before he began working with the view camera), Eggleston was a visual diarist, and Shore was a documenter of the American landscape.

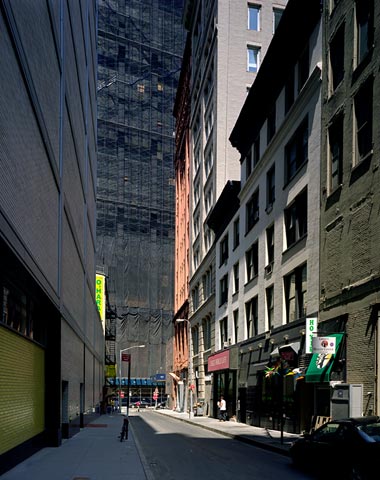

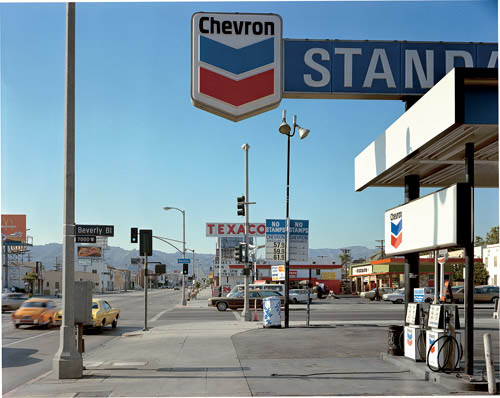

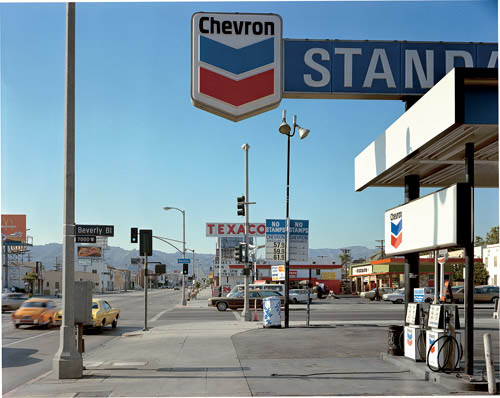

Stephen Shore

Beverly Boulevard and La Brea Avenue, Los Angeles, California, June 21, 1975

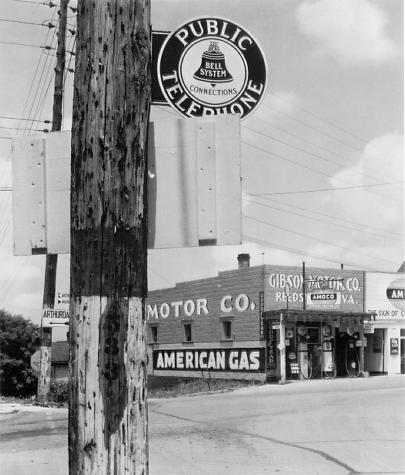

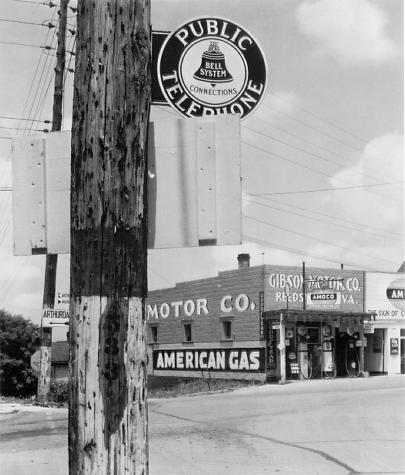

The landscape that Shore photographed was not the picturesque idealized panoramas of Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, or Carlton Watkins. In fact, as I recall it, many people were angered by Shore’s dystopian view of the American highway. The photographs were bland, random, and lacking a point of view–visually and politically. At the Maryland Institute where I went to school before transferring to Cooper Union, sneering at Shore’s work was the norm, and no one seemed to make the connection to Walker Evans’ pioneering take on the American landscape.

Walker Evans

Gas Station, Reedsville, West Virginia, 1936

For me, Shore’s work was revelatory. Having been schooled in the decisive moment, I immediately recognized that Shore was doing exactly the opposite. He was finding timeless, non-moments, and in the process revealing a landscape that was all around us, the outer fringes of cities, parking lots, silent streets, the bric-a-brac of culture and advertising reaching out into the no longer pristine environment of the US and Canada. Ultimately, Shore’s pictures were inclusive and open to interpretation. Less anecdotal, and more about the totality contained within the frame.

Stephen Shore

California 177, Desert Center, California, December 8, 1976

Most of this is obvious now. We’ve become accustomed to seeing this way, thanks to Shore, and others. But at the time this was clearly not work that appealed to the camera club crowd–it was work that challenged the protective boundaries of the photography tribe. The connection to Warhol, the early one man show at the Metropolitan Museum, and the way in which the art world sat up and took notice all contributed to separating him from “regular” photographers.

In retrospect this all seems like nonsense. Shore is both a regular photographer and a unique artist. Seeing the exhibition at ICP is to realize how beautifully transcendent the 1970s view camera work is. I doubt that the original C prints ever looked as balanced and vivid as the new digitally made prints. I know from printing my own work from the early 80s that time has not been kind to the film. My guess is that Shore’s negatives have been better stored than mine, but even so, I would imagine that scanning and color correcting was a major undertaking.

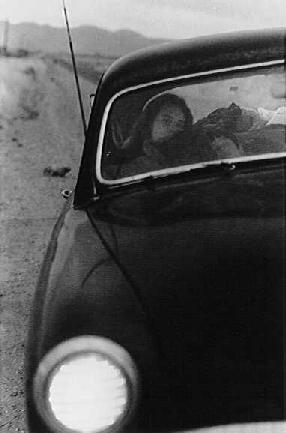

Robert Frank

U.S. 90, en route to Del Rio

It’s especially fitting to acknowledge Shore’s work in relation to the 50th anniversary of Jack Kerouac’s book On the Road because it is part of that American impulse to take to the highway and chronicle what one finds there–both visually and psychologically. Kerouac is, of course, more closely associated with Robert Frank generationally and stylistically. With Shore the temperature is lower, the sense of movement through space slowed. Stream of consciousness has been replaced by a more systematic cataloging of facts and surfaces. Earnestness, while not absent, is tinged with irony and an astringent eye.