Jefferson Davis gravesite, Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia — © Brian Rose

Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond is the final resting place of Jefferson Davis the president of the Confederacy. His statue is visited regularly, and Confederate flags are often placed around the monument. Elsewhere in the cemetery, John Tyler, the 10th president of the United States, is buried. Staunchly pro slavery he aligned himself with the Confederacy. And there are 18,000 Confederate soldiers buried in the rolling hills of this hauntingly beautiful place perched above the James River. I wrote about Hollywood a few years ago here and here.

***

I have mixed feelings about the removal of Confederate Civil War monuments for a number of reasons that have not received much attention in the wake of the the shocking events in Charlottesville, Virginia. And I’d like to explore the subject especially with regard to Richmond, a city I know well. Although I have lived much of my life in New York City, I was born and raised in Virginia, and went to the University of Virginia for two years. My family lived briefly in Richmond, but most of my childhood was spent nearby in Williamsburg, the restored Virginia capital.

First of all, let me be clear. I do not regard Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, or any of the other Confederate leaders worthy of veneration. Whether they were brave in battle or noble in defeat makes no difference. As W.E.B. DuBois wrote about Lee in 1928: His personal comeliness, his aristocratic birth and his military prowess all call for the verdict of greatness and genius. But one thing–one terrible fact–militates against this and that is the inescapable truth that Robert E. Lee led a bloody war to perpetuate slavery.

Many historians and commentators have pointed out that most of the Civil War statues were erected well after the war was over – after Reconstruction – when Jim Crow laws institutionalized segregation and the repression of African Americans. Mitch Landrieu, the mayor New Orleans, gave an eloquent speech just hours before the removal of the city’s Confederate statues pointing out the facts in a compelling manner:

These statues are not just stone and metal. They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.

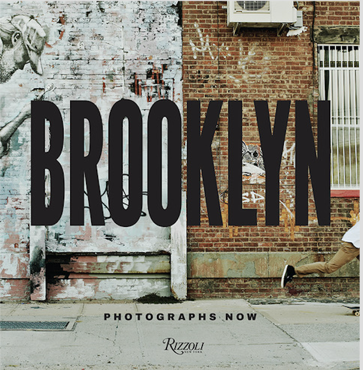

Henry Ward Beecher, Brooklyn, New York — © Brian Rose

The Henry Ward Beecher statue in downtown Brooklyn honors the leading abolitionist of his day — some called him the most famous man in America. His sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin. But even Beecher’s statue has a problematic element. A supplicant slave reaches up to the great man in gratitude.

***

While it is true that these monuments were intended to promote the myth of the Confederacy as a noble cause, they were also an expression of the Beaux Arts movement, which transformed American cities by creating broad boulevards, public parks, and grand classically inspired architecture. The Beaux Arts period, running from 1890 to 1920 corresponds almost exactly with the commissioning of Civil War monuments. In the North, most of the statues, of course, portrayed Union heroes like Ulysses S. Grant or William Tecumseh Sherman. In the South, it was Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. These statues were typically situated in prominent ceremonial places in major cities throughout the United States.

The best sculptors of the time were commissioned to produce these heroic monuments. The most prominent was Augustus St. Gaudens who created the Sherman statue at the corner of Central Park and Fifth Avenue. An angel leads the beatifically rendered Sherman on his path of destruction and victory. St. Gaudens’ masterwork is the Shaw memorial on the edge of Boston Common, completed in 1897, which depicts, in meticulous detail, Colonel Robert Shaw leading a black regiment down Beacon Street on their way to battle.

In the South, the civic goals corresponded with those in the North — to elevate public space with works of grandeur and nobility. Richmond, the former capital of the Confederacy best exemplifies the city beautiful movement. A grand boulevard was envisioned west of downtown with designated sites for monuments at major cross streets. The first to be erected was an equestrian sculpture of Robert E. Lee created by the French artist Antonin Mercié, fabricated in France, and shipped to the United Sates, much like the Statue of Liberty.

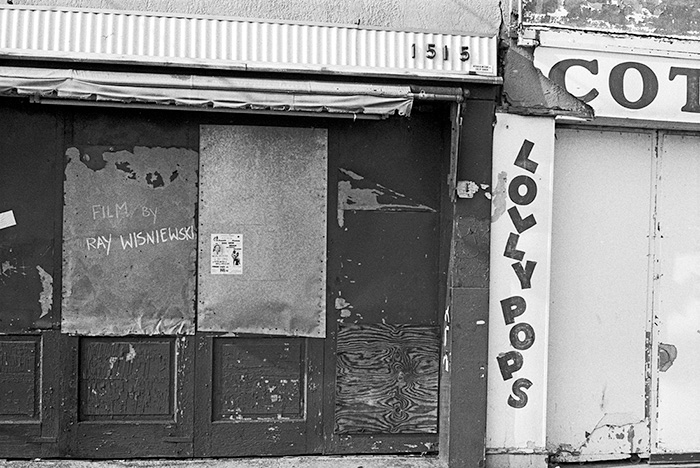

Washington at Valley Forge, Williamsburg, Brooklyn — © Brian Rose

Henry Shrady was the creator of the Robert E. Lee equestrian sculpture in Charlottesville. The city’s decision to remove the statue led to protest marches by hundreds of neo-Nazis carrying weapons, torches, and Confederate flags. Three deaths resulted. Shrady was also the sculptor of George Washington at Valley Forge, a powerful presence at the foot of the Williamsburg Bridge in Brooklyn, New York.

***

The J.E.B. Stuart monument in Richmond was created by Frederick Moynihan, who produced sculptures in the North and South depicting both Union and Confederate heroes. He and other artists of Monument Avenue were American, but all studied with the leading sculptors of the time in Europe. In Charlottesville, Virginia, the now infamous Lee Statue was sculpted by Henry Shrady who also is responsible for the Grant monument directly in front of the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. I have no idea if it mattered to Shrady which side of the “War Between the States” he was memorializing.

There were many, however, who understood what Lee represented to the dominant white society of the South. When the Lee monument was proposed in the 1890s, black members of the Richmond city council opposed it. One of them, John Mitchel, the editor of the Richmond Planet wrote: “The capital of the late Confederacy has been decorated with emblems of the ‘Lost Cause,” and the Lee statue represented a “legacy of treason and blood.”

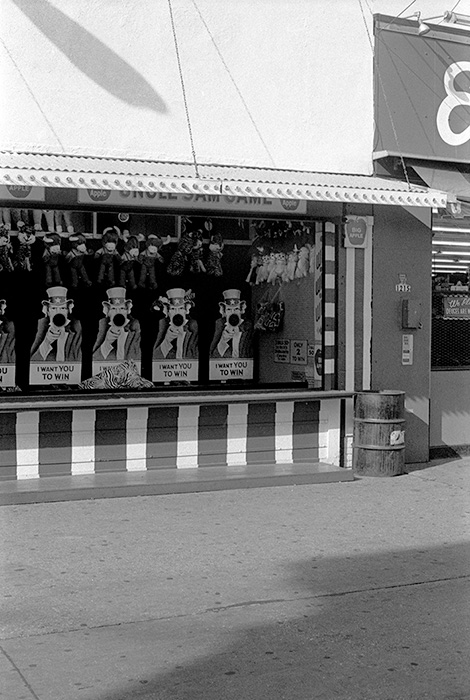

Ulysses S. Grant, Brooklyn, New York — © Brian Rose

The Grant monument on Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn was designed by William Ordway Partridge who also was commissioned to create a sculpture of Pocahontas in Jamestown, Virginia. Few New Yorkers know the Grant monument, but the Pocahontas sculpture is popular, and the image of this Native American icon is a fascinating study in itself of American mythology and history.

***

That’s where we are today. Richmond, a greatly rejuvenated city of over 200,000 people, about evenly divided black and white, is grappling with the future of its monuments. Ten years ago the city sought to balance the story of Monument Avenue by erecting a statue of Richmond native and former tennis great Arthur Ashe. The statue is awkwardly executed, too small in scale for its site, and comes off as an add-on rather than an integral part of the avenue’s overall ensemble. Are there contemporary artists who can do life-like sculptures worthy of St. Gaudens? Should we even try?

The people of Richmond will decide for themselves what to do, but I see two possible scenarios. One is to keep the monuments, and introduce a serious and comprehensive program to provide historical context, which will require an honest appraisal of Robert E. Lee, one that sets straight the fictitious myth of the noble warrior. The other is to relocate the statues – a major task presenting its own set of quandaries – and the commissioning of new works to replace the old – installations that respect the urbanistic and historic nature of the boulevard, but address contemporary issues and new aesthetic visions.

I agree that maintaining the status quo is no longer tenable. The Confederate battle flag should certainly not be flying from public buildings, and it’s time to acknowledge that the Lost Cause of the South belongs in the dustbin of history. But if it’s possible in the heat of the moment to slow down, let’s consider the options available for our monuments, Civil War and otherwise. In many cases, these are significant works of art that reflect the rebuilding of American cities, North and South, at the beginning of the 20th Century. The wholesale removal of monuments is an erasure of history rather than an attempt to understand it and learn from it.