Williamsburg, Brooklyn — © Brian Rose

After the storm.

Long Beach, New York — © Brian Rose

Children at Play.

Rockaway Beach, New York — © Brian Rose

Slices ‘n’ Ices.

Kingsbridge Road, The Bronx — © Brian Rose

Elevated subway platform.

Caesars Casino, Atlantic City — © Brian Rose

In all the brouhaha about Public Theater’s production of Julius Caesar I’d like to point out that I made the connection to Shakespeare in a blog post on the day Trump’s inauguration. I used the quote below:

Men at some time are masters of their fates.

The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars,

But in ourselves, that we are underlings.

Cassius is trying to persuade Brutus to join the insurrection against Caesar, which in the case of the play leads to the assassination of the leader returning from war. In a literary sense it is about taking action as opposed to being a passive observer — that history is not determined by fate, but belongs to those who seize the moment.

The assassination of Caesar, however, does not lead to the triumph of Cassius and Brutus, but to their own deaths and the ascendence of Mark Antony. The empire is preserved, but at great cost.

As in all of Shakespeare’s tragedies, there are battles, literal and psychological, over honor and moral rectitude. Blood is inevitably spilled, and the heroes are often victims of their own flaws. Shakespeare’s plays are both highly dramatic entertainment and complex interrogations of human character.

Caesars Casino and the abandoned Trump Plaza in rear, Atlantic City — © Brian Rose

I wasn’t able to see the Public’s interpretation of Julius Caesar in Central Park (closing tomorrow) with Caesar portrayed as Donald Trump. One assumes, based on the plot of the play, that the murder of “Trump” should be seen as a cautionary tale. Violence leads to more violence, and to tyranny. We are left understanding that change must come through our democratic institutions, and when necessary, in the streets — peacefully.

That Trump supporters do not see this — or willfully refuse to see it — is, of course, to be expected.

Beach 116th Street, Rockaway Beach — © Brian Rose

Despite becoming a cool beach destination in recent years, Rockaway Beach still has its scruffy aspects. There are SROs, nursing homes, and low income projects. There was a time when the beach was a convenient place to dump things — and people. There are also blocks and blocks of neatly kept houses.

Beach 116th Street, Rockaway Beach — © Brian Rose

Chewing out a rhythm on my bubble gum

The sun is out and I want some

It’s not hard, not far to reach, we can hitch a ride to Rockaway Beach

Up on the roof, out on the street

Down in the playground, the hot concrete

Bus ride is too slow, they blast out the disco on the radio

Rock-rock, Rockaway Beach

Rock-rock, Rockaway Beach

Rock-rock, Rockaway Beach

We can hitch a ride to Rockaway Beach

— The Ramones

Rockaway Beach boardwalk — © Brian Rose

Rockaway Beach was badly hit by Hurricane Sandy back in 2012 — hard to believe it was almost five years ago. The damage is still evident, though much has been rebuilt along the beach in the Rockaways. Elevated modular structures house a lifeguard station and restrooms. The wooden boardwalk has been replaced with a sturdier concrete surface that is less comfortable to walk on barefoot. We didn’t hitch a ride like the Ramones, but took the NYC Ferry back to Manhattan, which is a great ride, and only $2.75.

Long Beach, New York — © Brian Rose

Despite the it’s bucolic “field of dreams” image, baseball has urban roots. Before the development of suburbs after World War II, baseball was a city game played in vacant lots, and even in the street. The development of the suburbs changed the geographic and socio-economic basis of the game, and the rising popularity of football and basketball displaced the primacy of baseball as the great American pastime.

But baseball is still played in the city on scruffy fields caged behind yards of chain-link fencing. My son, Brendan, is one of a relatively small number of New York City kids who made it all the way through Little League to college ball. I’ve journeyed to dozens of games in the Bronx and all over the five boroughs. These fields are not glamorous places — unlike nearby Yankee Stadium. They don’t engender much nostalgia, though I still feel somewhat attached to Pier 40 on the Hudson River in lower Manhattan, a disused passenger ship terminal converted into a recreational facility.

But baseball is still played in the city on scruffy fields caged behind yards of chain-link fencing. My son, Brendan, is one of a relatively small number of New York City kids who made it all the way through Little League to college ball. I’ve journeyed to dozens of games in the Bronx and all over the five boroughs. These fields are not glamorous places — unlike nearby Yankee Stadium. They don’t engender much nostalgia, though I still feel somewhat attached to Pier 40 on the Hudson River in lower Manhattan, a disused passenger ship terminal converted into a recreational facility.

Monroe High School, The Bronx, New York — © Brian Rose

Baseball is played on fan-shaped fields, while New York is a city of rectilinear blocks. It’s not a natural fit. Nevertheless, baseball remains deeply associated with the city historically and in the present. In Greenwich Village Little Leaguers play on J.J. Walker field hemmed in by a high outfield fence to prevent well-struck balls from breaking windows across the street. And in the Bronx, housing projects overlook Monroe High School where many of the best Latino players in the city learn the game.

Atlantic City — © Brian Rose (4×5 negative)

President Trump has a magnetic personality and exudes positive energy, which is infectious to those around him. He has an unparalleled ability to communicate with people, whether he is speaking to a room of three or an arena of 30,000. He has built great relationships throughout his life and treats everyone with respect. He is brilliant with a great sense of humor . . . and an amazing ability to make people feel special and aspire to be more than even they thought possible.

— Hope Hicks, White House spokeswoman

Trump Taj Mahal, Atlantic City — © Brian Rose (see more Atlantic City photos)

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

Donald Trump and King Salman of Saudi Arabia

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread

For he on honey-dew hath fed,

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

(from Kubla Khan by Samuel Coleridge)

Broadway, one week after 9/11 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

The three books I have published in the past seven years comprise a New York trilogy — the city seen and explored over an extended period of time. Taken together they form a portrait of New York, especially lower Manhattan, during a period of extreme transformation. I hesitate to say “unprecedented” because change is integral to the nature of New York going all the way back to the first Dutch settlers.

The story told in these books relates to past photographic projects even to the way in which Marville and Atget documented Paris during the remaking of the city under Haussmann. I was familiar with all of that history when I began photographing the Lower East Side in 1980. At the same time, I was influenced by contemporary strains of street, architectural, and landscape photography. Color was an exceptionally new thing when I started this work in the 1970s, Today, it is the default photographic medium. As I was exploring New York with my camera, I was also discovering color’s descriptive nature, and its capacity to reveal as well as obscure.

These books also form a personal narrative, and I have kept my voice present throughout the text accompanying the photographs. I was 23 when the first images were made, and 62 when the most recent were done. At the center of this trilogy — though not seen directly — the World Trade Center was destroyed by terrorists on September 11, 2001. That wrenching event propelled the city forward, inexplicably, as a complex barely understood motive — and simultaneously, propelled the nation backward, convulsively, to the present moment of political crisis.

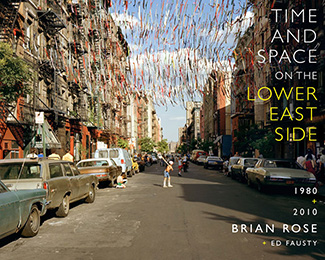

Time and Space on the Lower East Side is a portrait of place, one of America’s most vibrant and historic neighborhoods seen over a span of 30 years.

Time and Space on the Lower East Side is a portrait of place, one of America’s most vibrant and historic neighborhoods seen over a span of 30 years.

The trade edition of this book is, unfortunately, sold out, though used copies can be found on the internet.

The limited edition is still available — signed books in a slipcover with an 8×10 inch print inside.

Purchase the limited edition or browse images and reviews here.

Metamorphosis. Meatpacking District 1985 + 2013 is before/after view showing rthe dramatic transformation of the former meat market of New York City. Rose spent several days in 1985 photographing the neighborhood with a 4×5 view camera. The negatives remained in a box unseen for over three decades. Rediscovered a few years ago, the images portray the streets and architecture of New York, stunningly empty, but vividly real.

Metamorphosis. Meatpacking District 1985 + 2013 is before/after view showing rthe dramatic transformation of the former meat market of New York City. Rose spent several days in 1985 photographing the neighborhood with a 4×5 view camera. The negatives remained in a box unseen for over three decades. Rediscovered a few years ago, the images portray the streets and architecture of New York, stunningly empty, but vividly real.

There are only 150 copies of this book still available.

Purchase the trade or limited edition of the book here.

WTC is a visual history of the Twin Towers and the rebuilding of the city after 9/11. It serves as both historical record and personal story going all the way back to 1977 when the Trade Center was only a few years old and Rose was a newcomer to the city.

WTC is a visual history of the Twin Towers and the rebuilding of the city after 9/11. It serves as both historical record and personal story going all the way back to 1977 when the Trade Center was only a few years old and Rose was a newcomer to the city.

WTC pivots off of 9/11 with a series of images made directly after the destruction of the Towers, and moves forward to the ascendance of One World Trade Center on the skyline.

Purchase the trade or limited edition of the book here.

Stephen Shore, Wilde Street and Colonization Avenue, Dryden, Ontario, August 15, 1974

Forty-two years ago, an exhibition called New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape caused a stir in the photography world, and the controversy around it, surprisingly, has continued to ripple down through the decades. I was 21 in 1975 when William Jenkins mounted his now famous exhibition of landscape photography. I was in art school in Baltimore, and just beginning to shoot in color. No one at the Maryland Institute – teachers or students – was doing anything like what Jenkins highlighted in his exhibition, and certainly not color landscape photography.

Scene from Red Desert, Michelangelo Antonioni, 1965

It took longer in those days for new ideas to percolate through the image making community, especially if you were not in New York City, or Rochester, the home of the George Eastman House where the exhibit took place. My strongest influences at that time were masters of the 35mm camera like Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander, but perhaps to a greater extent, I was fascinated by the color imagery of Michaelangelo Antonioni’s films from the 1960s and 70s, especially Red Desert and The Passenger. Consciously or unconsciously, I set out to bridge those worlds – socially aware street photography and the more studied color landscapes of Antonioni’s movies.

Joel Meyerowitz, ‘Camel Coats, New York City’, 1975

In 1975 I was basically following my instincts, not exactly in a vacuum, but at a remove from the groundbreaking shows that were coming out of the Museum of Modern Art under the leadership of the enormously important curator John Szarkowski. At some point, I came across several images by Stephen Shore, William Eggleston, and Joel Meyerowitz, pioneers of color photography. Seeing those pictures printed in a magazine, it was as if the future flashed before my eyes. I knew what I needed to do.

By 1977 I was in New York where I studied with Meyerowitz at Cooper Union. It was the heyday of Light Gallery, which was one of the few galleries in the world dedicated to serious art photography. I remember seeing Frank Gohlke’s pictures of grain elevators at the Museum of Modern Art, and became familiar with Joe Deal and Robert Adams, particularly their images of the expanding suburbs of the American West. The way in which many of these photographers stayed back a bit, and allowed the detail afforded by the large format to do the work, appealed to me. When I photographed the Lower East Side in 1980 I turned to the 4×5 view camera as the best way to describe the neighborhood and its architecture.

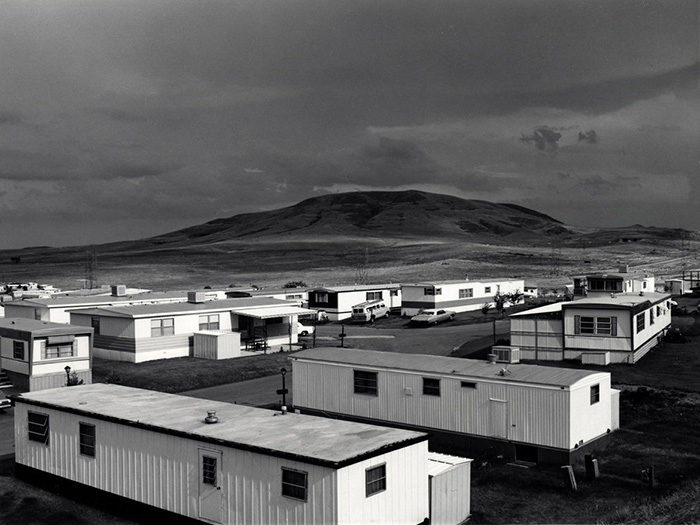

Robert Adams, Mobile Homes, Jefferson County, Colorado, 1973

I don’t remember when I became aware of the term New Topographics, but for me it was a curator’s thing – I was interested in individual photographers whose work I found compelling. To me, Robert Adams’ images possessed an almost spiritual power that transcended labels and art theory speak. At the same time, his pictures expressed the uneasy symbiosis of our relationship with the natural world. That is true to some extent of all of the photographers that Jenkins grouped together in his show.

That’s where Jenkins was most persuasive, I think, to point out that landscape photography had moved away from the romantic idealization of the world epitomized by Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. I’m afraid, however, that Jenkins unintentionally diminished the individuality of the photographers he chose for New Topographics. Placed in the same cubbyhole, the singular richness and complexity of their images was diluted by proximity, and this diverse group of photographers were seen to be part of some kind of group think. At the same time, many viewers were put off by the cool temperature of the images, the way in which visual content was diffused over the entire frame, rather than organized hierarchically.

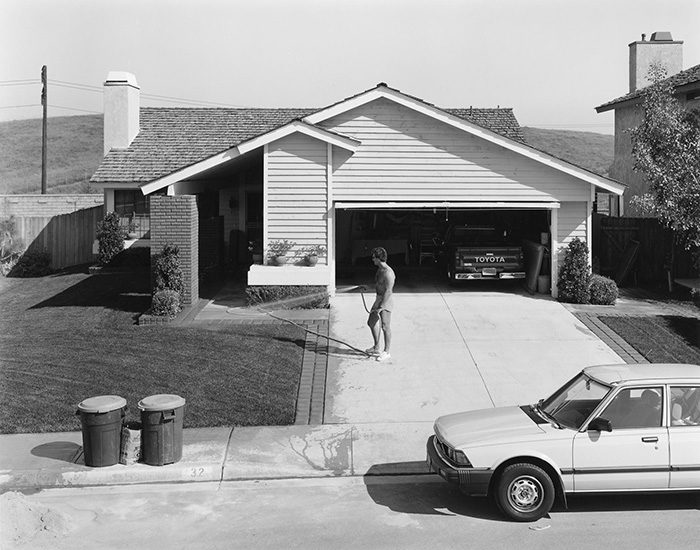

Watering, Phillips Ranch, California, 1983

Recently, in a Facebook group about contemporary landscape photography, a contributor suggested that too much of the work posted there looked derivative of New Topographics. I don’t actually know what that means. I suspect it refers to the wide angle, evenhanded, approach that many of Jenkins’ selected photographers employed. But that seems to me a narrow criterion for work by markedly different photographers. Are we talking about Lewis Baltz? Stephen Shore? Henry Wessel? New Topographics was a cuator’s thesis supported by the work of a number of talented photographers who eschewed conventional approaches to landscape. But it was never a movement, nor a particular style.

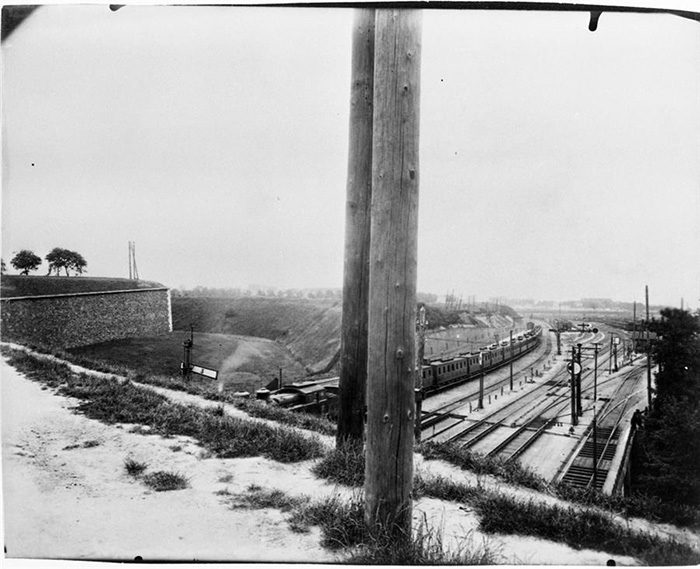

Charles Marville, Demolition of Butte des Moulins for Avenue de l’opera, 1870

The reality is that photographers have been documenting human presence on the landscape since the medium was invented. It could be argued that the photographs of Ansel Adams and others depicting a pristine picturesque world were the true aberrations, and that the New Topographics photographers were actually extending — in various different ways — an unbroken line running through Marville, Atget, O’Sullivan, Evans, and others. The Düsseldorf School photographers who are often connected to New Topographics were undoubtedly influenced by this continuum inspired as well by German photographers like August Sander and Albert Renger-Patsch. Even the more conceptual work of Bernd and Hilla Becher echoes that history.

Albert Renger-Patzsch, Winter landscape with colliery Pluto in Wanne-Eickel (1929)

Walker Evans, Birmingham Steel Mill and Workers’ Houses, 1936

Walker Evans, Birmingham Steel Mill and Workers’ Houses, 1936

Lee Friedlander, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1980

As photographers we need not feel enslaved to curatorial constructs like New Topographics. What Williams Jenkins came up with was a timely recognition of the way in which photographers were becoming attentive to the accelerating encroachment of urban development in the late 20th century. That attention and the formal rigor of the images ran counter to the prevailing aesthetics of fine art photography, which had already been challenged by Winogrand, Frank, and other small camera practitioners. In my view, the whole uproar around New Topographics had less to do with an aesthetic or conceptual break than it had to do with a reconfiguration of the photography world including the growing importance of museums, curators, art schools, and galleries.

Eugène Atget, Porte de Bercy, 1910

Let’s not get distracted by all this. In my view, the critical observation of the landscape by photographers remains an important if not essential practice. With the explosion of new technologies, the increasingly inward gaze of virtual reality, and the lure of alternate notions of truth, the counter weight of objective observation keeps us attentive to the physical world we continue to inhabit with its ongoing environmental depredations, spasms of war and destruction – and beauty — wherever we may find it.

St. Nicholas Church, under construction, WTC — © Brian Rose

When the Twin Towers were destroyed on September 11, 2001, a small Greek Orthodox church, St. Nicholas, was obliterated by the falling debris. A replacement church designed by Santiago Calatrava is now under construction a short distance from the original structure. I snapped the picture above returning from an appointment at the 9/11 Museum offices. My book, WTC, will soon be available in the museum shop.

St. Nicholas Church, 1981 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose/Edward Fausty

The original church served a small congregation just south of the WTC on Cedar Street. The building, converted from earlier use as a tavern, stood alone on a parking lot. Photographers were fond of tilting up at the cross with the Twin Tower rising above. It was a perspective that Edward Fausty and I avoided when we made our picture back in 1981.

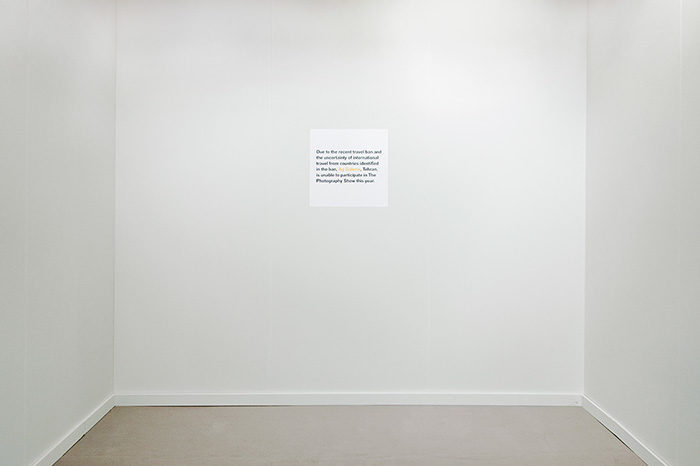

Empty AIPAD booth — © Brian Rose

There are hundreds of booths at AIPAD (The Photography Show) and thousands of people attending. Lots of different languages overheard while walking around, which is typical of New York.

But one booth is empty. The sign says:

Due to the recent travel ban and

the uncertainty of international

travel from countries identified

in the ban, Ag Galerie, Tehran,

is unable to participate in The

Photography Show this year.

Ran into several friends, Hans Knijnenburg from the Netherlands who is avid photo book collector, Art Presson and Eve Kessler, who have a wonderful photography collection, Joel Sternfeld, the photographer, and I met Hendrik Kerstens, the Dutch photographer who I wrote about in my blog a number of years ago.

DART, the newsletter for design professionals and photographers, is promoting the work of artists who are responding to the election of Donald Trump and the current political fallout from this national disaster. Today, my Atlantic City project is being featured. Thanks go out to Peggy Roalf for providing a showcase for this work and that of other artists.

The full project, Atlantic City: In the Wake of Destruction left by Donald Trump, can be viewed here.

Dillon + Lee booth at AIPAD

I am pleased to be in this year’s AIPAD (Association of International Photography Art Dealers) show at Pier 94 on the westside of Manhattan. I’ve attended several times in the past, but this is the first time I’ve had a piece on display. AIPAD provides a great overview of what the galleries are showing in New York and beyond. My gallery, Dillon + Lee, is not exclusively a photography gallery, but they have assembled a diverse stable of artists that includes a significant number who work with photography. I hold down the landscape view camera department.

AIPAD show — East 4th Street 1980 (Rose/Fausty)

I am showing a 4×5 foot print of one of the Lower East Side photographs made in 1980 by me and Edward Fausty. It’s the cover image of Time and Space on the Lower East Side, and it was taken in front of the building I lived in at the time. It is, perhaps, the most iconic of the Lower East Side images, and although shown a lot, it’s still one of my favorites.

Dillon + Lee booth at AIPAD

If you are serious about photography collecting — or want to see what is going on the photo gallery world — it is definitely worth the $30. There are more than 100 dealers and galleries represented, and they have added a section on photo book publishing this year, which I will be checking out. The show runs from March 30 – April 2.

Eons ago — about 10 years — when George Bush was president, I wrote with dismay about how reality was becoming more and more a relative concept, untethered from facts, infinitely malleable. I quoted a Bush administration aide who said:

”That’s not the way the world really works anymore,” he continued. ”We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will — we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which  you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

This was was from Time magazine, which still exists, despite the vast dispersion of the media across the internet in an information space that freely mixes social media and journalism, where rumor and fake news compete — and oftentimes win — over factually based reporting and observation.

Last week Time’s cover features only the text Is Truth Dead? This is where we are now. A dangerous con man was elected president on a wave of lies, disinformation, and willful ignorance. We are in big trouble.

There has been a lot of discussion over the years about photography and its relationship to truth and reality. You hear a lot about how Photoshop has undermined the credibility of the image. You hear terms like “post factual.” There are deeply mind numbing discussions about semiotics and the indeterminate nature of meaning — and truth. These themes make wonderful parlor discussions, and graduate school theses.

They are irrelevant right now. We are in an emergency. We need to employ words and images as we understand them — to drill down to what is essential and knowable in practical terms.

I’m sick to death of hearing things from

Uptight short sided narrow minded hypocritics

All I want is the truth, just give me some truth

I’ve had enough of reading things

By neurotic psychotic pigheaded politicians

All I want is the truth, just give me some truth

All I want is the truth, just give me some truth

All I want is the truth, just give me some truth

— John Lennon

UPDATE:

Case in point. I just received an email from a photography organization in the Netherlands promoting their next exhibition, Simulacrum. The basic premise of the show is that reality and manufactured reality are becoming indistinguishable. This is hardly an original concept — a curatorial container for a bunch of artists using technology to create alternative realities. I am not interested in this. I am interested in what artists have to say concretely and coherently — including those who make use of new technology. When we get waylaid by aesthetic and philosophical strategies that purposely blur the difference between truth and untruth in images and language, we run the risk of becoming complicit with the shape shifters and charlatans who seek dominance of our institutions and who currently occupy the White House in Washington, D.C.

Get real!

—

http://www.noorderlicht.com/en/photogallery/expected/

Simulacrum

What is real, what is artificial? The border between the two is beginning to fade. In the visual language of the advertising industry, the border between real photography and digitally calculated models is almost indistinguishable… It’s becoming somewhat of a challenge to distinguish between images that represent reality and images that depict reality. This theme lies at the heart of the exhibition: a Simulacrum stands for a simulation that takes the place of the reality it stems from.

Heinersdorf, Germany 1987 — from The Lost Border, The Landscape of the Iron Curtain

— © Brian Rose

Unsurprisingly, there are engineering firms and architects who are interested. One small architectural firm explains their willingness to participate:

To put it directly: we have never said that we are designing a wall. We are responding to the government’s solicitation for a new model of border infrastructure which we hope will provide a corrective to the privileging of iconicity, spectacle, and security at the border. (full text here)

Jake Matatyaou and Kyle Hovenkotter, JuneJuly, March 3, 2017

management@junejuly.co

We are barely two months into the Trump presidency and it’s been some scary ride. I have gotten a good start on my Atlantic City project, which highlights Trump’s bankrupt casinos as a jumping off point. I don’t know where things go from here — with my project, or with Trump’s reality TV show writ large. As the esteemed blogger Digby says, “He’s running the country like he ran the Taj Mahal.”

Most of my landscape projects have incorporated social/political issues, but this is by the most targeted, and the most connected to current events. So, in the interest of getting the work out into the world as soon as possible, I’ve taken the photographs I’ve run on my blog over the past few months and put them together in a mini-website. Please take a look — recommend to others. Resist!

Williamsburg, Brooklyn — © Brian Rose (Painting by Damien Mitchell)

Trump unmasked.

Update — a quote from Simon Schama’s piece in the Financial Times. I first came across Schama when living in the Netherlands. His book The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age is highly recommended along with his later Landscape and Memory.

He writes:

The challenge, as with all such imaginative counter-attacks, is the capacity to project the message beyond the halls of college and museum and into the street where it counts. Prints lend themselves perfectly to poster polemics but the most effective challenge may yet come from creative adventures in the digital media, where inspired derision coupled with the defence of truth can go viral. Should that happen, the complacent dismissal of resistance art as the self-indulgent playtime of a defeated “elite” will die on the faces of the powerful. Aux armes, les artistes!

https://www.ft.com/content/0ded5de4-fe6d-11e6-96f8-3700c5664d30

Trump Taj Mahal, Atlantic City — © Brian Rose

By the time I get back to Atlantic City, these images of Trump Taj Mahal and Trump Plaza will almost certainly be gone. Workmen were busy removing any signs of Trump’s involvement in Atlantic City when I was there less than two weeks ago. But the evidence will not be easily erased.

In 2015, the Trump Taj Mahal was fined $10 million for money laundering.

“Trump Taj Mahal received many warnings about its deficiencies,” said FinCEN Director Jennifer Shaky Calvery. “Like all casinos in this country, Trump Taj Mahal has a duty to help protect our financial system from being exploited by criminals, terrorists, and other bad actors. Far from meeting these expectation, poor compliance practices, over many years, left the casino and our financial system unacceptably exposed.”

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

United States Department of the Treasury

Press release — March 6, 2015