Inside the Statue of Liberty — © Brian Rose

The world waits for the Republican putsch to fail in the final hour.

Museum of Modern Art — © Brian Rose

Way back when — the late 70s — I studied with Hans Haacke, the distinguished political/conceptual artist. Although I did not go in that direction as a photographer, it was an important experience for me, and I have believed ever sense, that art should be grounded in historical and political context, that it needs to interact dialectically with the world we live in. This process, to me, does not necessarily resolve the questions surrounding truth and beauty, but it exposes or illuminates the language — visual or textual — that we use when we talk about these ineffable things.

Does this make sense to you? Maybe, maybe not. It’s a little dangerous going down this road, especially a road so well-trodden and rutted as to be, perhaps, irrelevant.

In New Photography 2013 at the Museum of Modern Art we get to go down this and other well-worn paths concerning conceptual/polemical photography. Curator Roxana Marcoci asserts that “there has never been just one type of photography,” as if throwing down a gauntlet. Her show presents a group of photographers who “have redefined photography as a medium of experimentation and intellectual inquiry.” In this show it is not enough to focus attention on individual artists who are attempting to stake out some small scrap of new turf in an already expansive field. No, they must be doing something truly ground breaking, “creatively reassessing the meaning of image-makingtoday.”

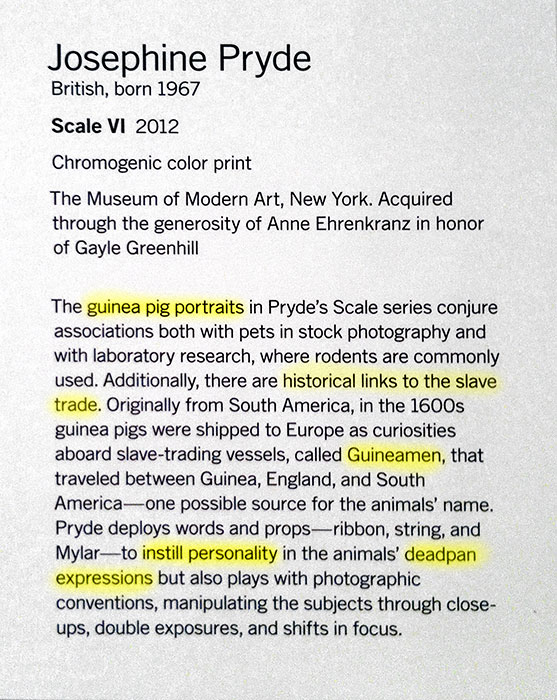

Museum of Modern Art text panel

Please read the text panel above. It is, of course, not necessary or desirable to actually see the photographs. The meaning is in the text. Were one to encounter the above guinea pig portraits unburdened of their meaning, one might miss the “historical links to the slave trade,” and one might gaze in bafflement at the “ribbon, string, and Mylar” intended to animate the “deadpan expressions” of these furry rodents.

One might, in all likelihood, not care one way or another about any of these photographs, and move on to other, hopefully more trenchant, examples of social and aesthetic engagement. Say, for instance, the Walker Evans “American Photographs” upstairs in the museum, which still look pretty new 75 years after they were made.

I believe this is one of those moments characterized by the expression “jumping the shark.” In this case guinea pigs.

Tribute in Light 2013 (digital) — © Brian Rose

Tribute in Light 2013 (digital) — © Brian Rose

I was up in the Bronx photographing a Fordham University office space. After that I headed down to Brooklyn with my assistant Chris Gallagher. I wanted to get an image of the Tribute in Light — two focused beams of light symbolic of the Twin Towers.

I’d been thinking of a good location for a while, and decided upon the park just above the Brooklyn Bridge near Jane’s Carrousel. We walked around for about an hour looking for a good spot. The area was swarming with photographers carrying everything from iPhones to zoom lensed SLRs. Unsurprisingly, I appeared to be the only person with a view camera.

I found my vantage point — at a safe distance from the shutterbugs — and alternated shooting with 4×5 film and the Canon 5D Mark III (for those interested in such things) that I’d been using for my earlier architectural shoot. The image above was made with the latter.

It was an exceedingly warm, muggy, and windless night. But good for long exposures with the view camera. Dozens of people took up stations nearby awaiting the lights. As it got darker I became aware of the amber glow from a nearby streetlight being thrown on my foreground. The result has a strange theatricality, almost like the different elements were pasted together.

I’m picking up the 4×5 film later in the day. It will be interesting to compare to the digital image..

This is an interview with me and my wife Renee Schoonbeek. First time, I think, we’ve been featured together. Bettery Magazine is an initiative of smart, the car company.

Here’s what it says on their “about” page:

Bettery Magazine is an online publication featuring the people, places and ideas that are changing our urban landscapes today. In giving their unique foresights an international stage, Bettery Magazine aims to encourage the creative thinking poised to reshape and revitalize cities around the globe.

On the street with a print from a 1985 image. (digital) — © Brian Rose

Everyone thinks I should do it, so I am working on a series of before/after images of the Meatpacking District. I originally photographed the area in 1985, also venturing uptown into west Chelsea. I had completed the Lower East Side project — which I later came back to — and I had finished photographing the Financial District — with an NEA grant. I had also begun photographing various NYC parks, and later that year I would begin my travels along the Iron Curtain border across Europe. But for a week or so in late winter of 1985 I wandered around the west side of Manhattan and documented the profoundly empty streets, like a stage set with the actors on break. Eventually, as we all know, the people would come.

Gansevoort Street 1985 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

Gansevoort Street 1985 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

Gansevoort Street 2013 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

Gansevoort Street 2013 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

My experience with photographing New York, however, does not always follow the usual expectations about then and now. And with the Time and Space on the Lower East Side I deliberately wanted to challenge preconceived notions about what change actually looks like on the streets of the city.

New York, even the relatively glittering canyons of Manhattan, remains an often gritty place. The Meatpacking District has become a center of fashion and art, but like Soho before it, it continues to show its utilitarian roots, and is still dominated by late 19th and early 20th century architecture. The Gansevoort Market is still in business under the High Line housing a number of meat purveyors. In the view above of Gansevoort Street, one has to look twice to see the changes. Florent, the famous restaurant from ’80s is gone, and another restaurant has taken its place. The storefront of the small reddish building is now a boutique, but much of the block remains empty — as a Maserati rumbles along the cobblestones.

Gansevoort Street 2013 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

Gansevoort Street 2013 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

As is often the case, “after” photographs can be less compelling than “befores.” The factors that led to the first image being made, are no longer present. These can be very subtle attributes, atmospheric, ineffable. So, part of my strategy in rephotographing the Meatpacking District is to look for new pictures, or variations on the originals. The image directly above was made a few minutes after repeating the 1985 picture. It is, perhaps, a better description of the block with the Standard Hotel looming in the background.

Washington Street 1985 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 1985 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 2013 (digital) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 2013 (digital) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 1985 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 1985 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 2013 (digital) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 2013 (digital) — © Brian Rose

I am shooting the new photographs in 4×5 film using a similar camera and lens as in 1985, but then scanning the negatives and working up the images in Photoshop. Some of the images here were taken with my point-and-shoot, which I usually have with me while working with the big camera. As the film gets processed and the images completed, I will replace the digital snaps with the final 4×5 photos.

Washington Street 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 2013 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 2013 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 2013 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Washington Street 2013 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

In a previous post, I wrote about this being the former location of the Mineshaft, an infamous men’s sex club closed at the height of the AIDS crisis just a few months after my photograph was taken in 1985. Now, other sybaritic delights beckon.

West 14th Street 1985 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

West 14th Street 1985 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

West 14th Street 2013 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

West 14th Street 2013 (4×5 negative) — © Brian Rose

The images above are both 4x5s. I made several pictures with the 14th Street Apple store clearly visible on the right, but stepping a few feet forward better duplicated the original image.

Hudson and 14th Street 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Hudson and 14th Street 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Hudson and 14th Street 2013 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Hudson and 14th Street 2013 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Little West 12th Street and West Street 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Little West 12th Street and West Street 1985 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Little West 12th Street and West Street 2013 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Little West 12th Street and West Street 2013 (4×5 film) — © Brian Rose

Pier 54 2013 (digital) — © Brian Rose

Pier 54 2013 (digital) — © Brian Rose

When I photographed the area in 1985, Pier 54 was an enclosed building as seen above. At present, only the steel structure of the facade remains. Occasionally the the otherwise empty pier is used for events. A small part of it is open to the public, and while I was there a couple of female skateboarders zoomed about while bicycles and joggers streamed along West Street.

Stay tuned for more pictures.

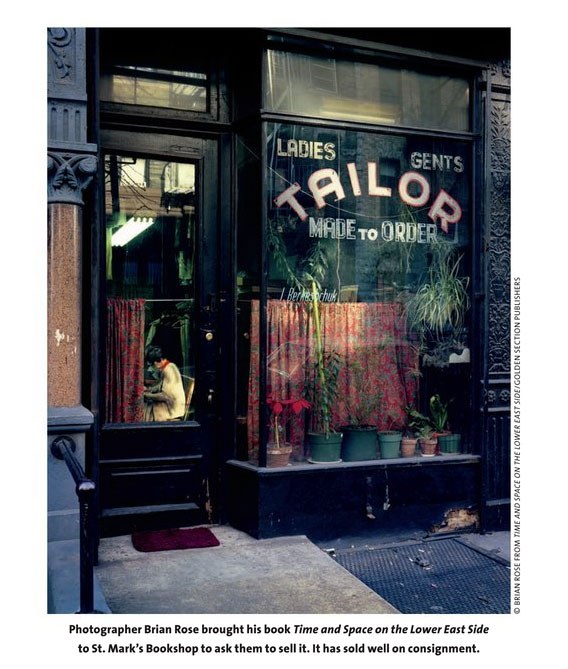

From the article What Bookstores Buy: St. Mark’s Bookshop in New York City:

St. Mark’s Bookshop has been located in Manhattan’s East Village for 35 years, first on St. Mark’s Place and now on 3rd Avenue. Co-owner Bob Contant, who purchases a variety of genres for the store, including photography and art books, says their customers reflect the diversity of New York City…

Consignment is also how the store handles self-published books. One recent example of a self-published photo book that was popular at St. Mark’s Bookshop is Time and Space on the Lower East Side by Brian Rose. The book compares photos Rose made in 1980 and 2010 at specific locations on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The photographer himself brought it to the store to ask that they sell it. Contant notes that it’s a good example of the type of photo books that do well in the store: “It’s a combination of subject matter and the fact that it’s sort of a historical document.”

The photo and caption above is from the August print edition of PDN.